|

MARS : A WARMER, WETTER PLANET - by Jeffrey Kargel

|

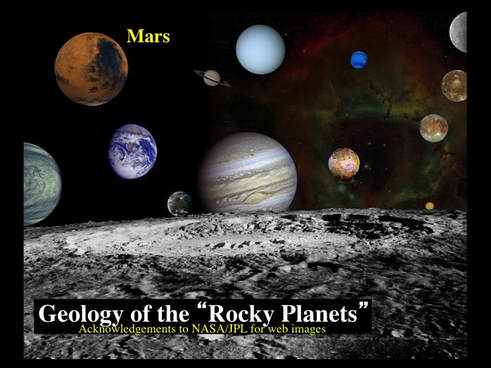

Over the past few years, I’ve talked to you about the geology of the Rocky Planets. That’s to say Mercury, Venus, Earth, our Moon, and Mars. Mars is very much uppermost in the minds of amateur astronomers with this autumn’s close approach to Earth, which gives us another opportunity to take a good look at our planetary neighbour through our telescopes. In fact, Mars has also been the subject of a host of books over the past few years, fueled in great part by the intense interest that the various American and European missions to Mars have generated, even with the general public.

The latest one that I’ve read was written by a geologist, Jeffrey Kargel. Mars – A Warmer Wetter Planet presents a fascinating, poorly known and controversial aspect of Mars. Kargel’s thesis is that the early planetary history of Mars was much warmer and wetter than what we see today, possibly with large bodies of standing surface water - maybe even a northern ocean. Now, none of this is very new as far as hypotheses go. However, what’s fascinating about this book is that it’s the first generally available compilation of geological evidence for the existence and action of Martian glaciers and ice sheets on a planetary scale.

However, although this book covers a fascinating topic and contains some extraordinary photographs to support the glaciation hypothesis, it is abysmally written! Even as a professional geologist, I had to work hard to follow much of the text. Kargel makes no concessions to the non-technical reader ! So why am I telling you about this book if it’s so badly put together ? Because it introduces us to a collection of images that NASA and JPL possess that beautifully illustrate the photographic evidence derived from orbiting probes that lend compelling support to the glaciation hypothesis. In fact, what I’m going to do here is show you those very same images, as presented by Kargel, that I found by Googling on the web.

However, although this book covers a fascinating topic and contains some extraordinary photographs to support the glaciation hypothesis, it is abysmally written! Even as a professional geologist, I had to work hard to follow much of the text. Kargel makes no concessions to the non-technical reader ! So why am I telling you about this book if it’s so badly put together ? Because it introduces us to a collection of images that NASA and JPL possess that beautifully illustrate the photographic evidence derived from orbiting probes that lend compelling support to the glaciation hypothesis. In fact, what I’m going to do here is show you those very same images, as presented by Kargel, that I found by Googling on the web.

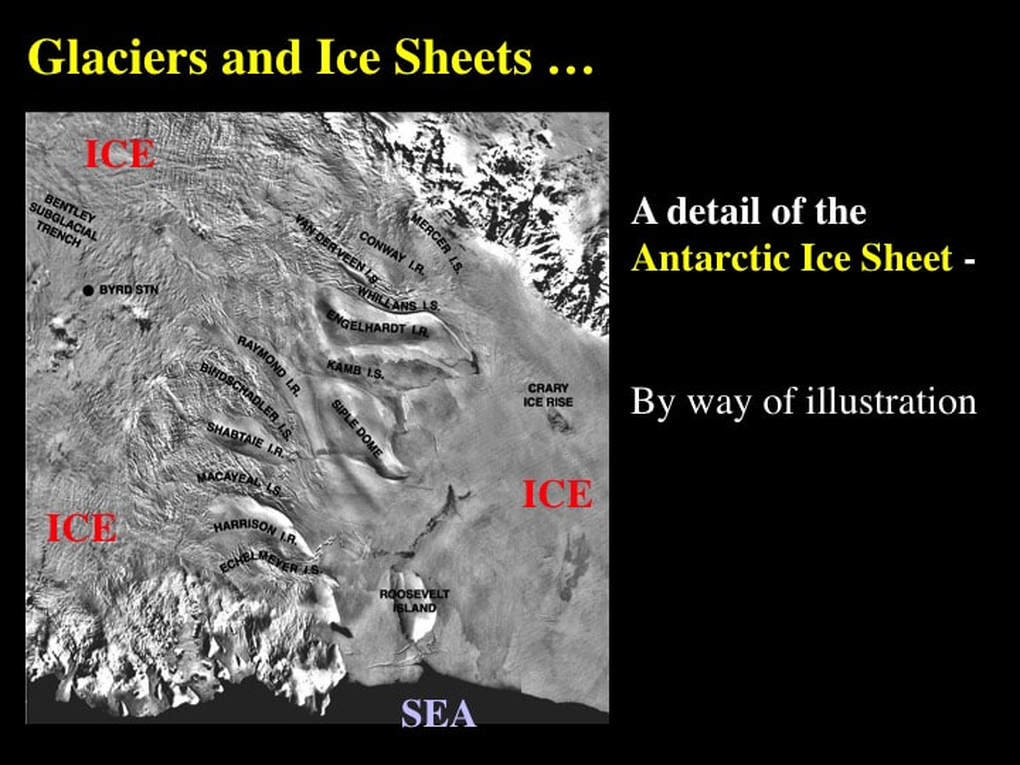

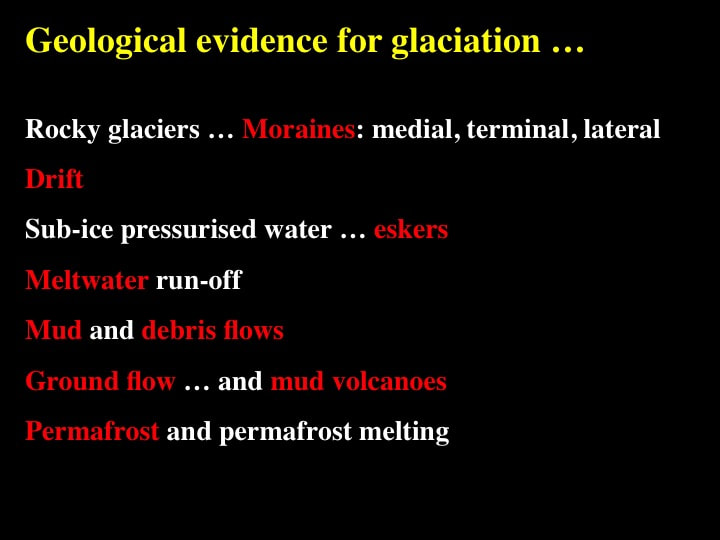

dGlaciers are tongues of ice that creep down valleys in mountainous terrain, while ice sheets can cover huge areas the size of continents here on Earth (examples include Greenland and Antarctica). Why “Warmer and Wetter” ? Because without an initially moist climate, clouds couldn’t form, snow couldn’t fall, ice couldn’t accumulate, and glaciers and ice sheets wouldn’t exist ! So, geological evidence for glaciers and ice sheets is therefore a proxy for a warmer wetter planet than what we see today. From observations on here Earth, geologists are well aware what constitutes evidence for the previous existence of glaciers and ice sheets. Glaciers and ice sheets flow and can carry huge volumes of rock that they dump anywhere along their track, either at the end of the glacier or ice sheet where it melts, along its sides = moraines, or anywhere under the ice = drift. Glaciers and ice sheets are commonly associated with meltwater, especially when they begin to melt wholesale, and meltwater is associated with very characteristic landforms such as eskers and mud or debris flows (I’ll explain these in just a moment). Sometimes the combination of lots of meltwater and the rock and other debris dumped by the ice makes the ground underneath and adjacent to glaciers and ice sheets highly plastic such that it flows like quicksand. We also know that the ground in front of and underneath glaciers and ice sheets can be frozen as permafrost that gives rise to other characteristic landforms. What Kargel has really done is to present the reader with selected details and close-ups of images from the NASA/JPL photo library in support of the glaciation hypothesis. So let’s have a look at some of the images Kargel uses …

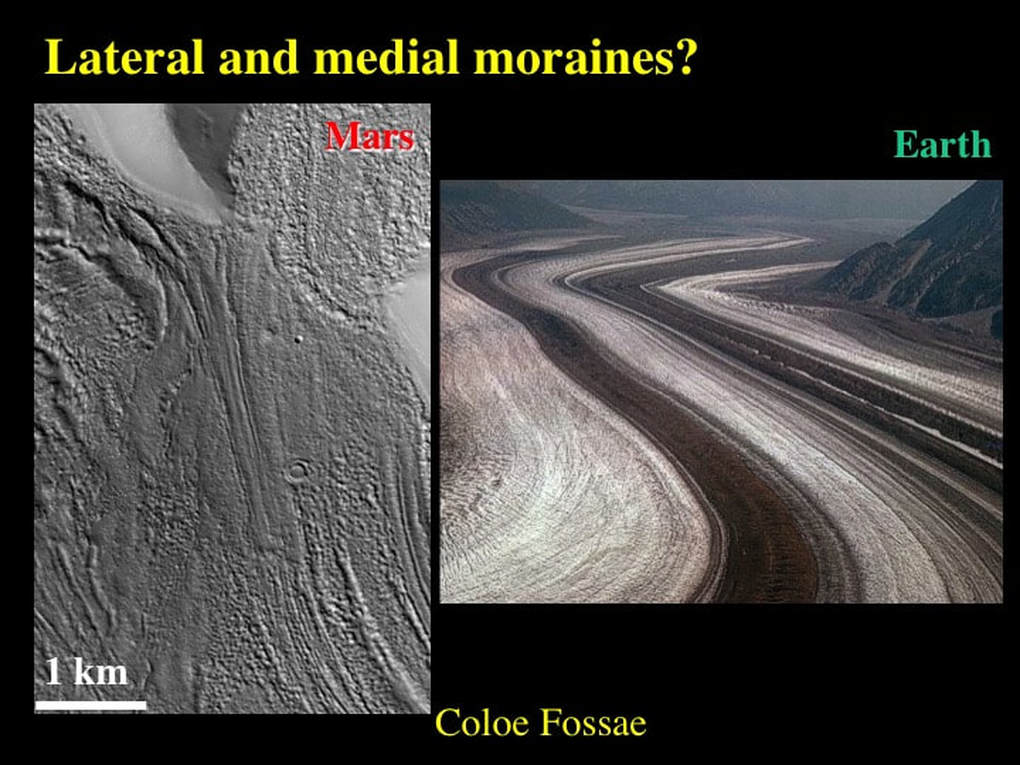

Here on your left is what Kargel interprets as moraines formed at the sides and within the flowing ice as two or more glaciers converge and coalesce. Notice how few impact craters there are in this image – and other images I’ll show you in a minute - implying that this is relatively young terrain ! Scale bar ! Very detailed image ! The image on the right is an equivalent from modern Earth. It’s important here to realise that Kargel is not suggesting that the martian image still preserves the ice from the glacier. Rather, he sees Martian glaciers as made of a mix rock and ice, such that the ice acts to lubricate the flow of the rock component : what we would then call rocky glaciers. In this - and the other images I’ll show you below - much of the ice has sublimated leaving the rock component behind to preserve the evidence for the flow of the original glacier.

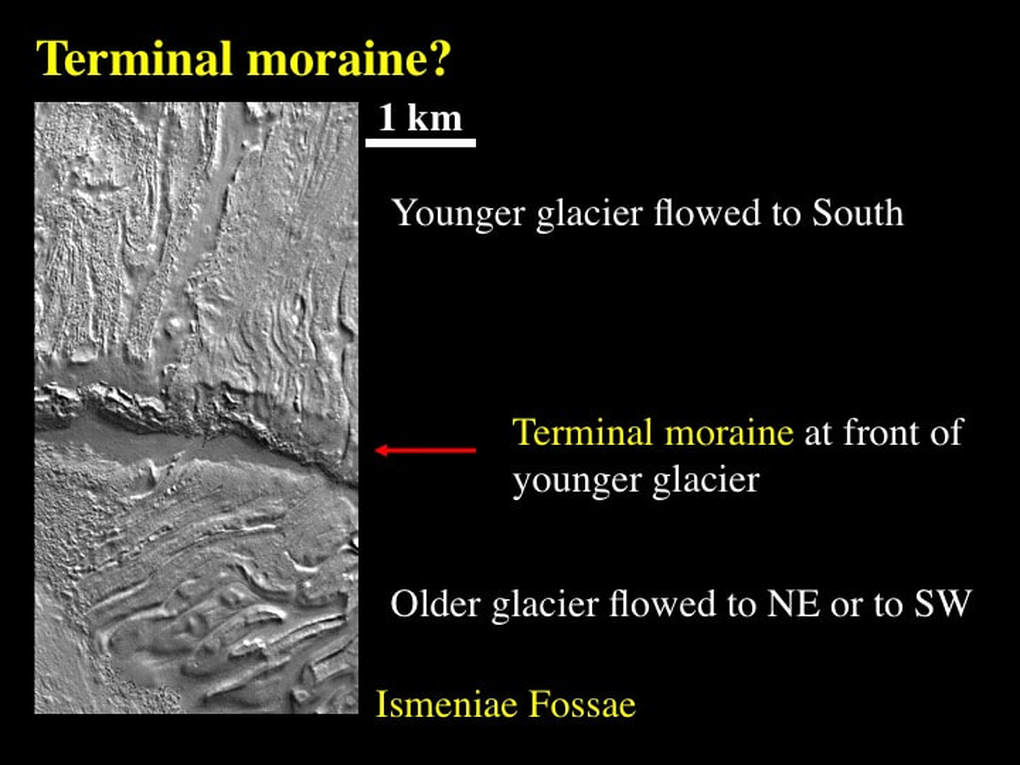

When a rocky glacier or ice sheet stops advancing, an equilibrium is established between the rate at which ice arrives at the glacier or ice sheet margin from upstream and the rate at which that ice melts or sublimates. The consequence of this is that the ice dumps its rocky debris content in the same place, in what’s called a terminal moraine. Kargel interprets this image in terms of an older rocky glacier in the south overlain by a younger one in the North. The younger one flowed from North to South and dumped its load of rock in an east-west trending terminal moraine that truncates the NE-SW flow lines in the older rocky glacier.

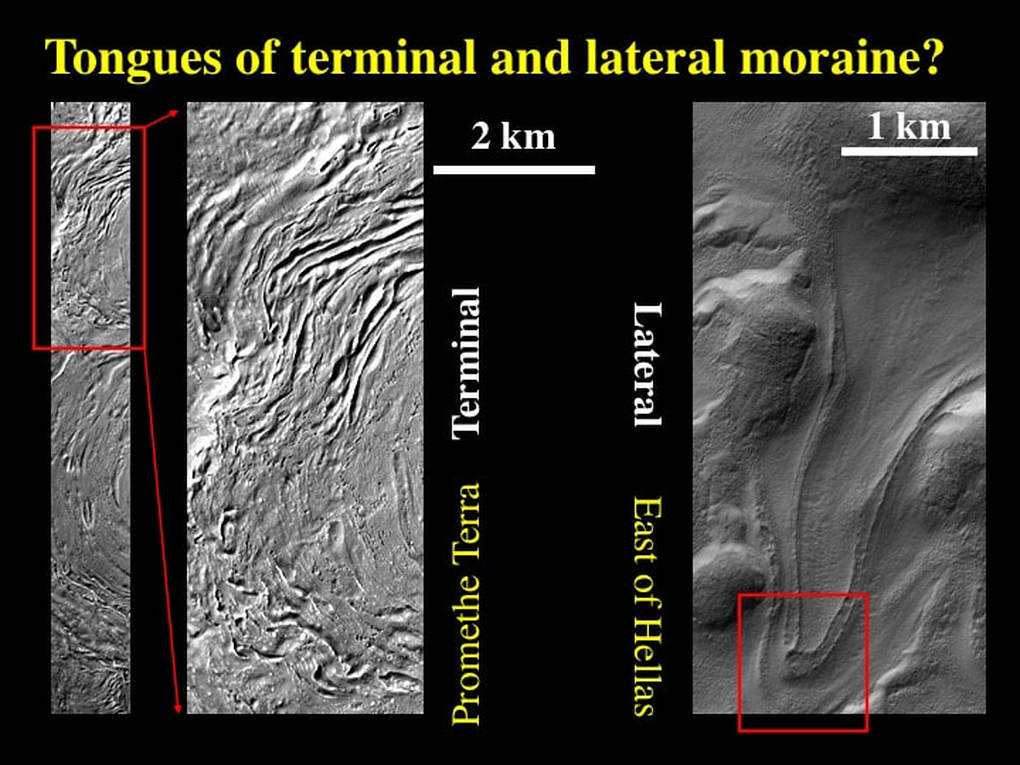

Here on the left is a detail of broad arcs that Kargel interprets as the ends of tongues of rock and ice, where the ice has subsequently sublimated leaving ridges of rocky debris to mark the end of the flow = terminal moraine ...

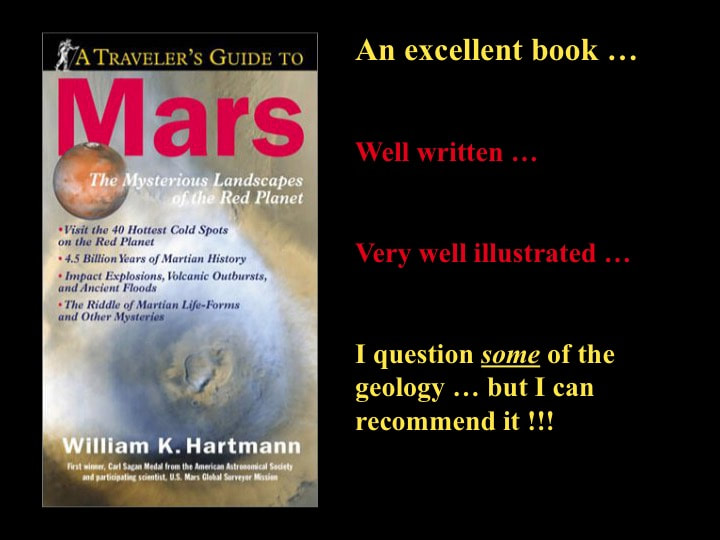

… and on the right you see the equivalent location (red box) from an image I have shown you before - taken from another recent book on Mars by William Hartmann - that clearly resembles a flowing glacier with both lateral and terminal moraines.

… and on the right you see the equivalent location (red box) from an image I have shown you before - taken from another recent book on Mars by William Hartmann - that clearly resembles a flowing glacier with both lateral and terminal moraines.

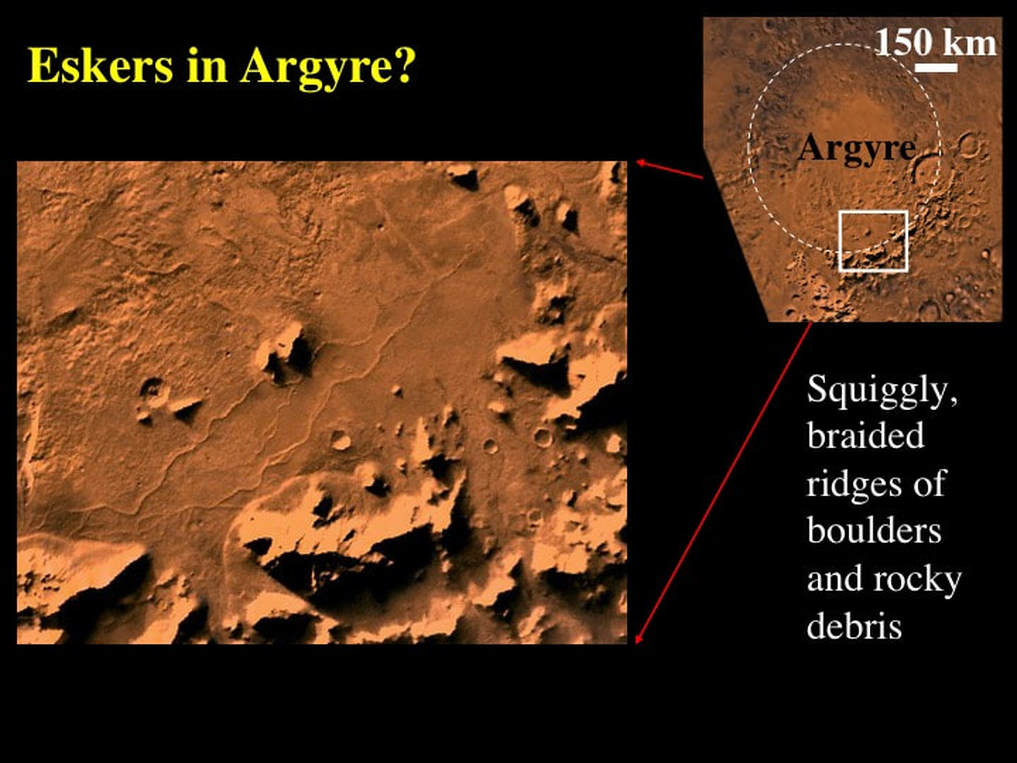

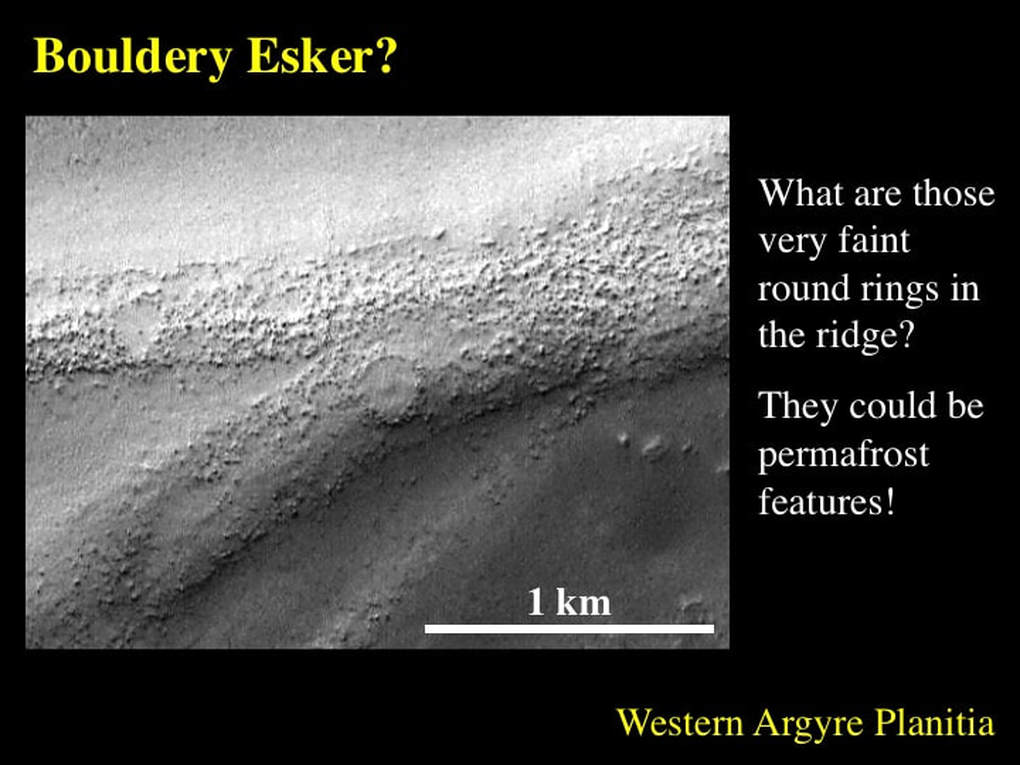

Kargel spends a good deal of his book talking about the Argyre Impact Basin, which he interprets to have been filled with flowing ice. In this image, he interprets the long squiggly ridges as eskers, which form when rocky debris is dumped by rivers of pressurised water flowing under the ice.

Branching bouldery esker ?

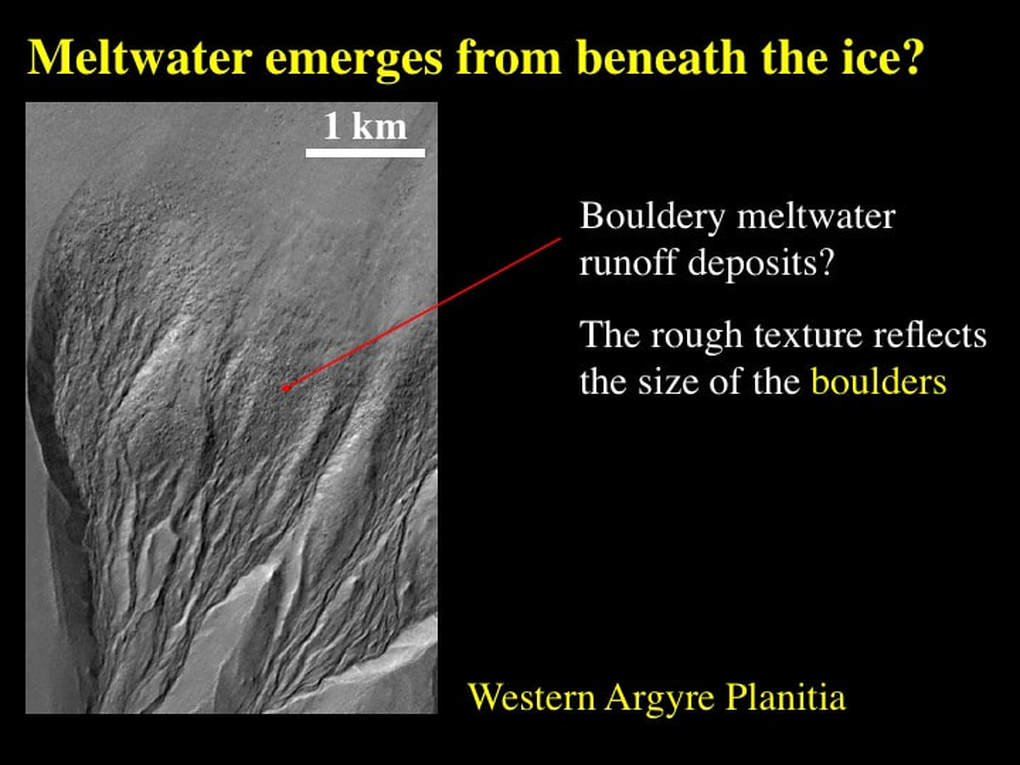

When this pressurised sub-glacial water reaches the margin of the ice and emerges at the planetary surface it would still be carrying lots of debris, but it slows down as it looses pressure, so Kargel interprets this fan-like feature as a bouldery deposit left by meltwater exiting in front of a glacier or ice sheet.

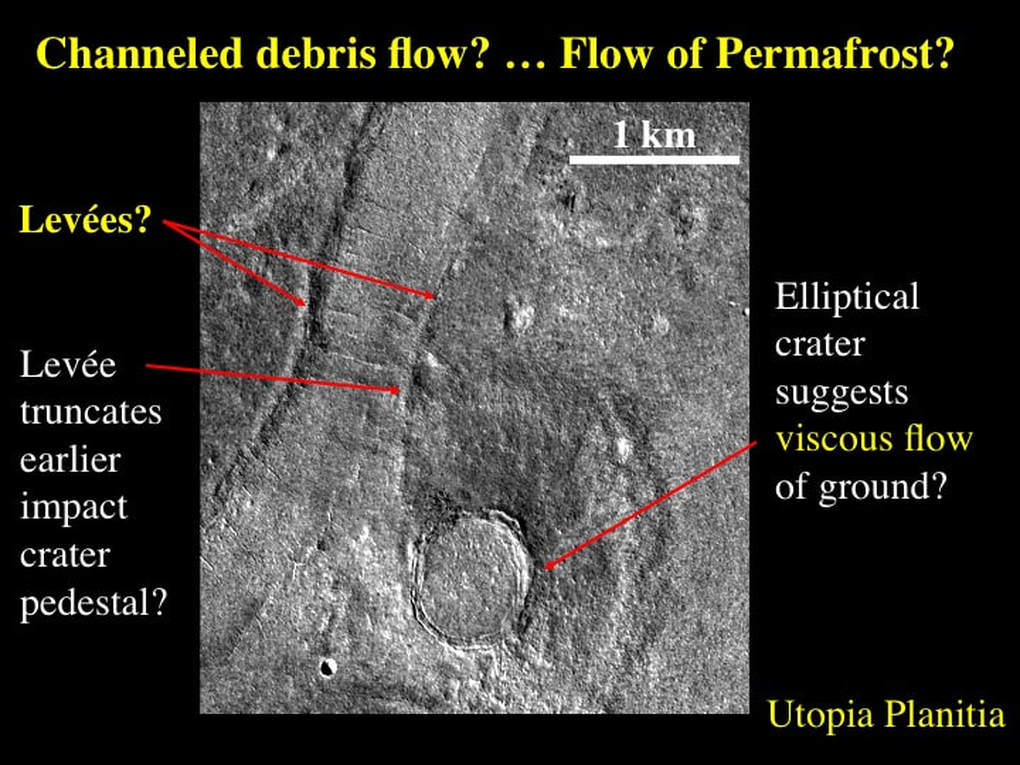

Surface water can flow in channels … and it can also still carry a lot of rocky debris mixed in with turbulent water : such flows are called slurries or debris flows. Kargel interprets this as a channeled debris flow with lateral levées or raised margins (just like the Mississippi River here on Earth, flowing through New Orleans. See how the channel cuts across an older crater, but the crater and the raised pedestal it sits on are not round ! Kargel interprets this to indicate that the ground flowed plastically because it was water-logged - after the crater formed, but before the channel was cut.

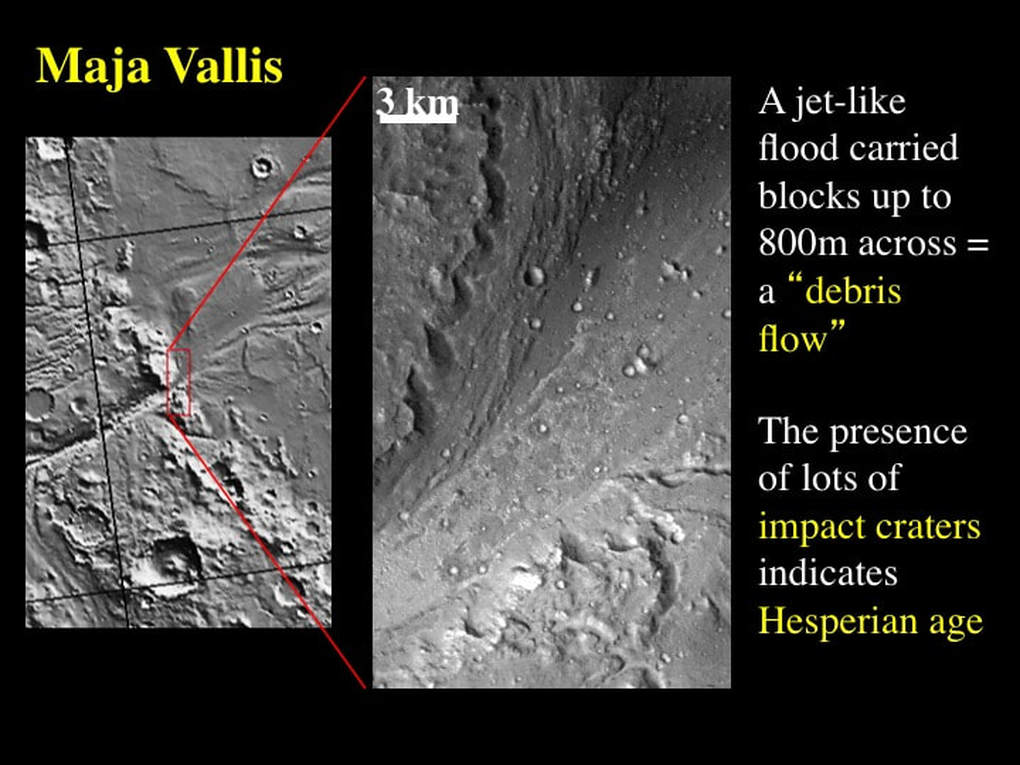

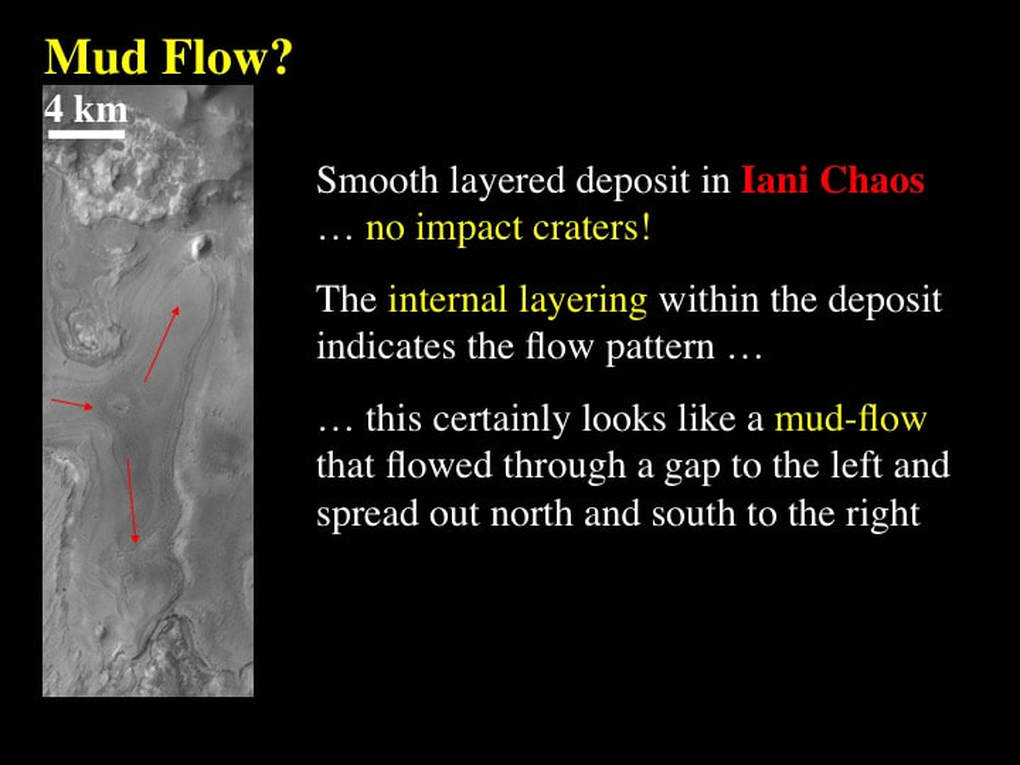

Not all of these debris flows are all that young. Notice the abundant impact craters in this one at the mouth of the Maja Valley. It certainly appears to be older than the terrains we’ve looked at so far here – perhaps suggesting that there were several periods of glaciation throughout Mars' history. As the flowing slurry of water and rocky debris slows down further it can only carry finer material : essentially sand and mud. Kargel interprets this image as a slow moving mud flow that passed between two promontories on the left and spread out north and south to the right. You can clearly see the finely detailed flow lines that mark the movement of the deposit.

Kargel interprets this image as a slow moving mud flow that passed between two promontories on the left and spread out north and south to the right. You can clearly see the finely detailed flow lines that mark the movement of the deposit.

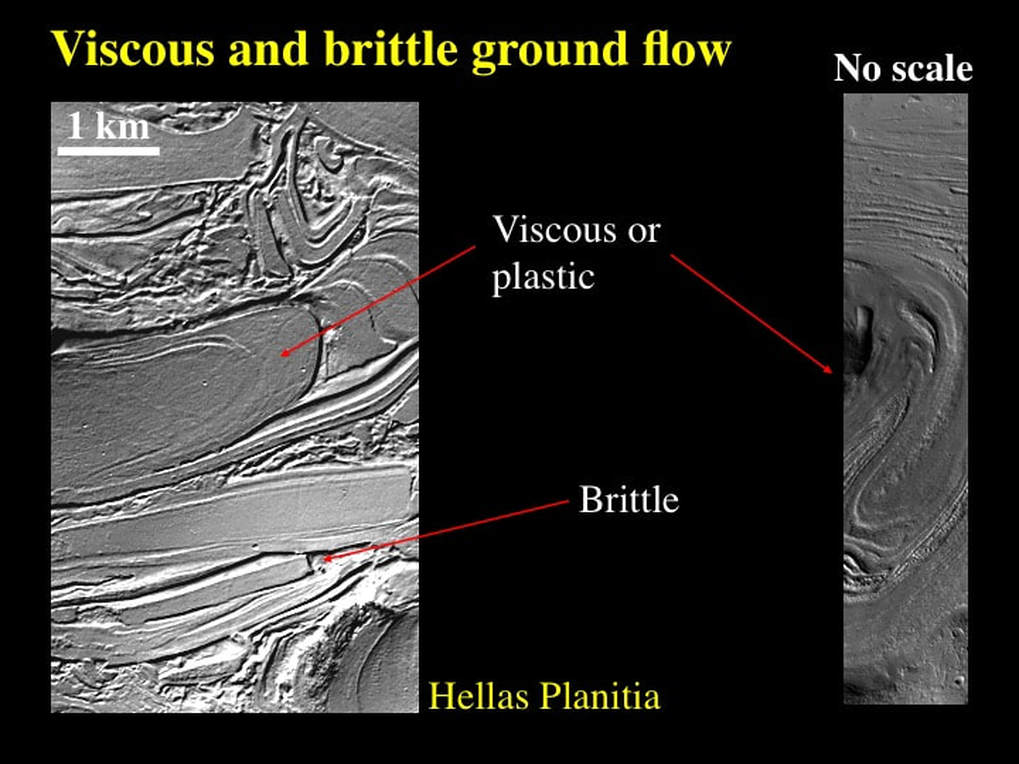

On Earth, ground in front of glaciers and ice sheets is commonly saturated with water, in part because of meltwater from the glaciers, but also because of the seasonal melting of permafrost. That means that the ground can flow plastically, like potter’s clay or like quicksand. Kargel interprets these amazing images in terms of horizontal ground flow, sometimes viscous, sometimes brittle - depending on the nature of the ground itself.

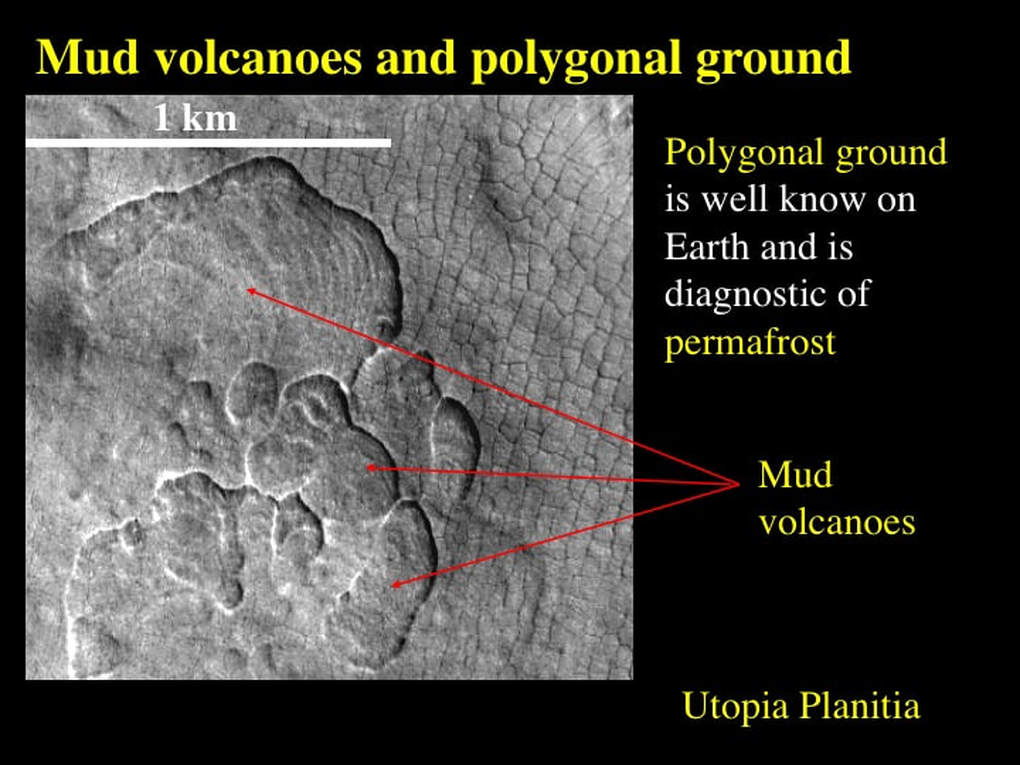

This image he interprets in terms of the vertical flow of cold, water saturated mud that erupted, rather like a volcano, through a denser overlying layer of sediment or rock. See how the lobes of the “mud volcanoes” have flowed over and covered older polygonal ground considered diagnostic of permafrost.

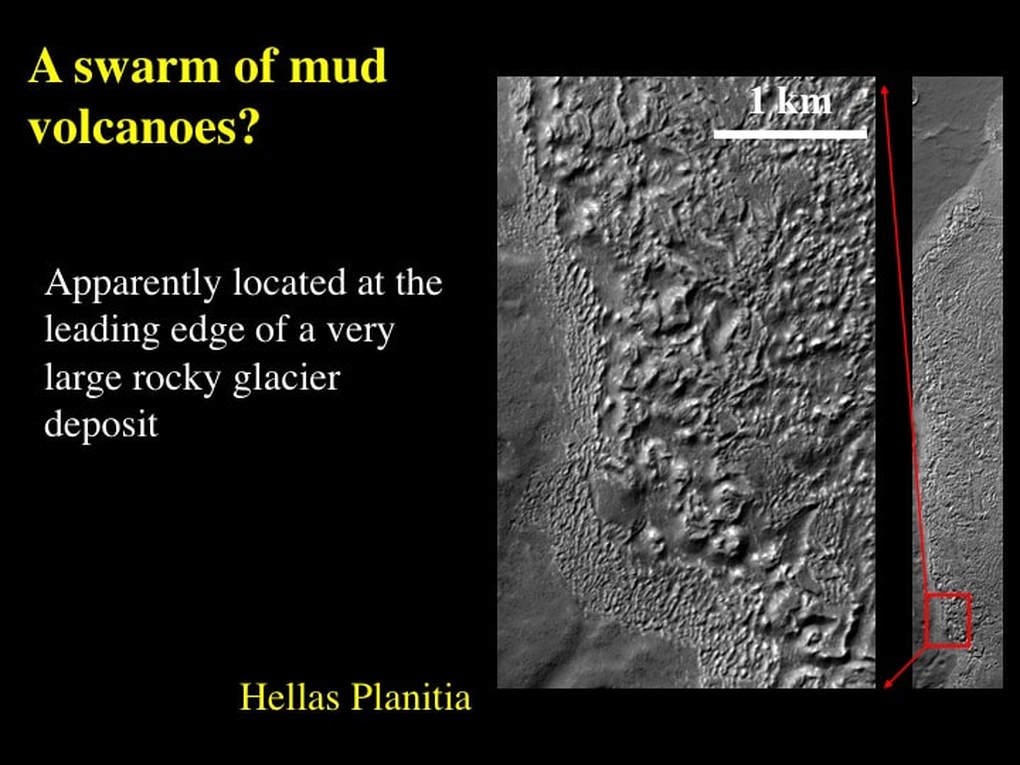

… and when you pull back far enough - Kargel interprets the knobby terrain in this image as a swarm of mud volcanoes.

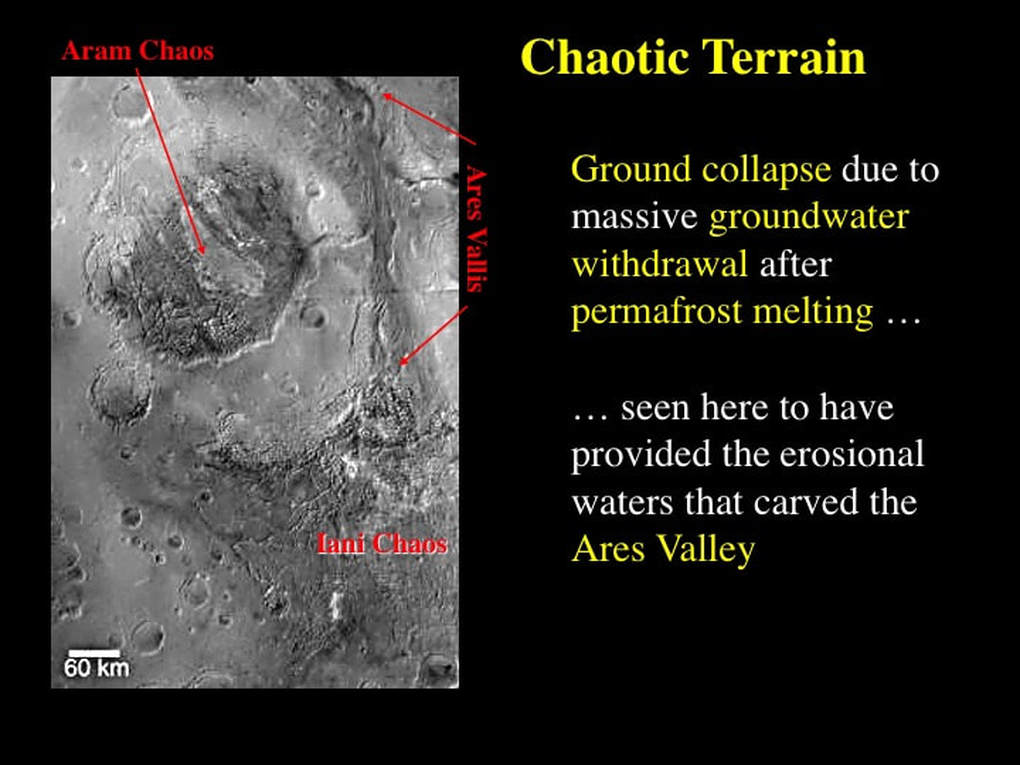

Kargel also presents some fascinating images that trace what happens to water released by the melting of permafrost, the kind of event that gives rise to the famous martian “Chaotic Terrain”. Here he illustrates how the water released by what he interprets as permafrost melting in two areas of chaotic terrain flowed into what was to become the Ares Valley.

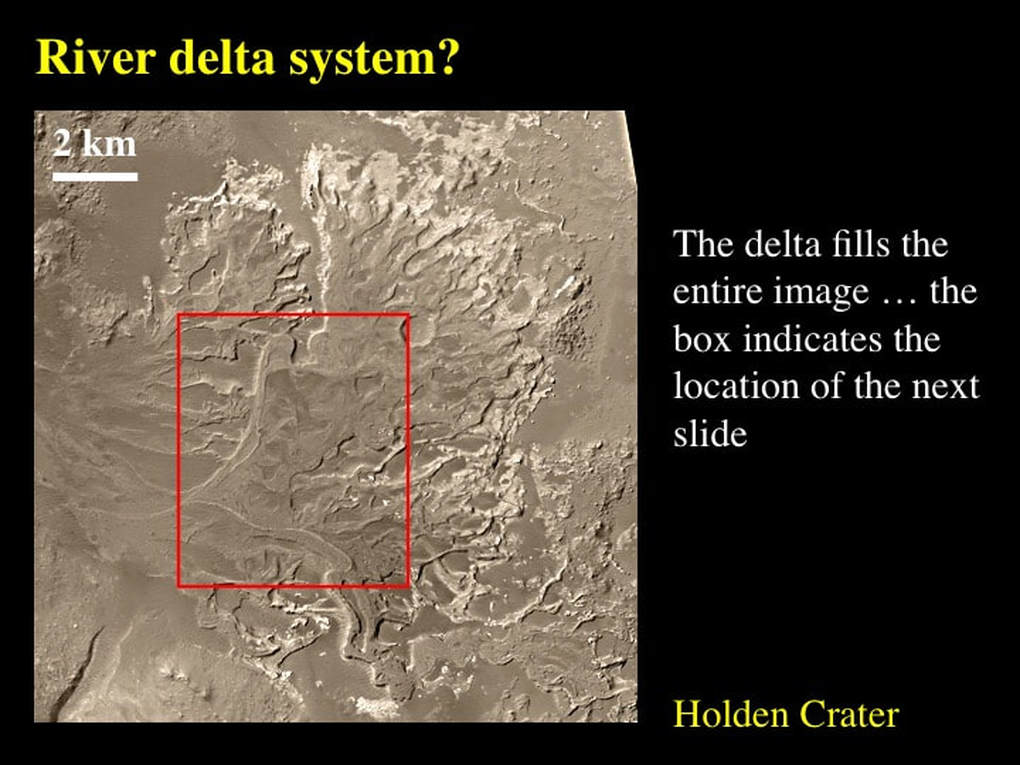

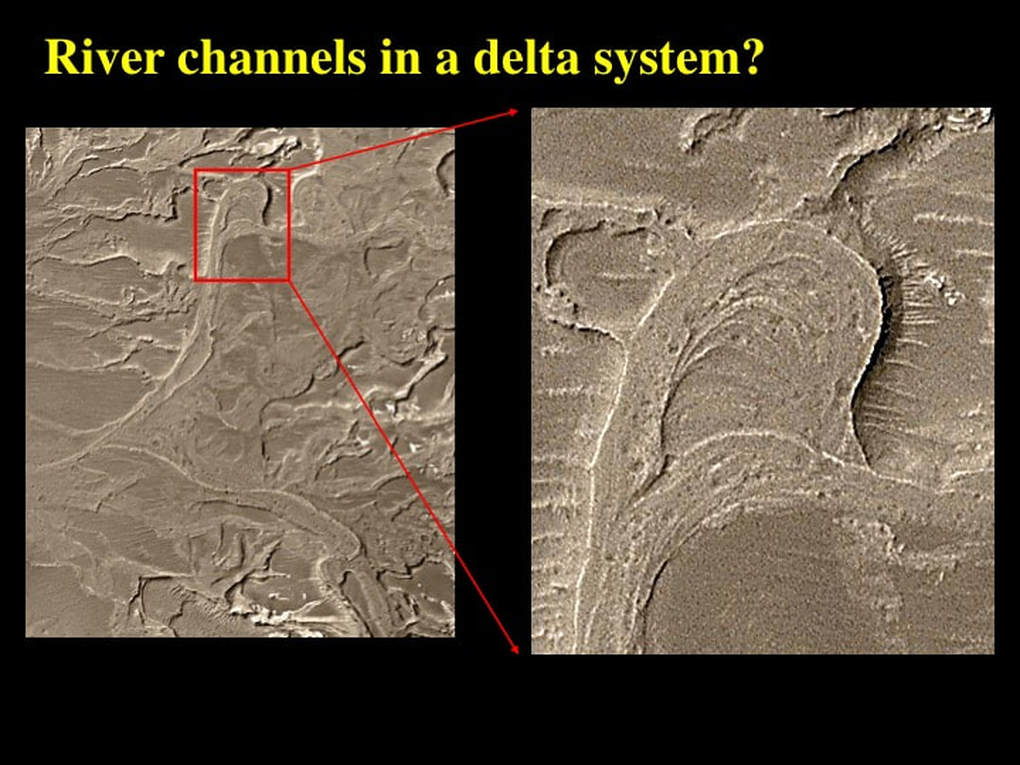

Kargel also addresses a key question with respect to martian surface water : how long did it hang around ? Were the channels we see carved by short-lived flash floods, or were there ever slow flowing, meandering rivers - like the Mississippi, but on Mars ? This image, and the details we’ll look at next, really bowled me over. Here you see a broad delta system that marks where flow in a river was slowed to a crawl as the river approached a large lake or sea of standing water. As we zoom in on the red box …

… on the left, you can see individual river channels carved out in the delta …. and if we zoom in again on the right : this is what Kargel interprets to be a series of cut-off meanders, or ox-bow lakes if you recall your physical geography from high school, which resulted from the progressive migration of meanders in slow flowing rivers over periods of 100’s to 1000's of years. Clearly, these features are NOT the result of flash floods !!

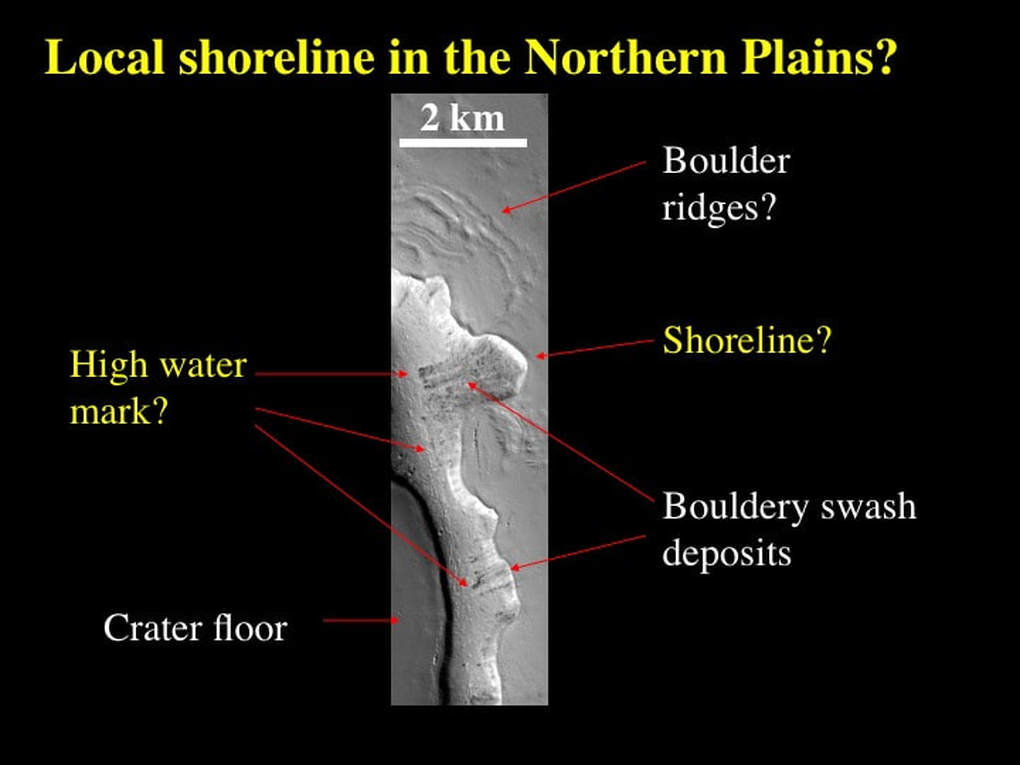

Well, as you know from geographers, poets and song-writers, rivers flow down to the sea and seas have shores - and when there are storms at sea there are storm features that show up on the shore lines. Kargel interprets this amazing image as the rim of an impact crater (lower left), topped by a high water mark at the left-hand limit of coarse boulder deposits with flow markings that imply currents coming from the right. He even marks a shoreline (low water mark) and boulder ridges that would have formed as banks and shoals offshore.

All of this is very exciting stuff, yet my remarks at the beginning of the talk suggest that I don’t like this book. Why ? First, it’s a very difficult book to read. Kargel makes no concessions to the lay-person. Second, despite the fascinating images, there are no direct linkages between the beautiful NASA/JPL photographs in the book and the extremely dense text ! In fact the photos aren’t even numbered, so you can’t tell which image he’s referring to anyway. Third, Kargel’s style is VERY annoying : his prose is VERY dense - worse, he seems to consider himself something of a renaissance man and leaps from fact to philosophy. Fourth, Kargel dedicates the latter part of his book to flights of fancy with scenarios of permanent settlement on Mars and terra-forming - which quite frankly should be confined to the realm of science fiction. Finally, it is so obvious that the book has not been properly edited. No editor would allow a science-based book to be published without adequate references between text and illustrations. Worse still, even the figure captions often don’t relate very well to what’s in the photos.

All of this is very exciting stuff, yet my remarks at the beginning of the talk suggest that I don’t like this book. Why ? First, it’s a very difficult book to read. Kargel makes no concessions to the lay-person. Second, despite the fascinating images, there are no direct linkages between the beautiful NASA/JPL photographs in the book and the extremely dense text ! In fact the photos aren’t even numbered, so you can’t tell which image he’s referring to anyway. Third, Kargel’s style is VERY annoying : his prose is VERY dense - worse, he seems to consider himself something of a renaissance man and leaps from fact to philosophy. Fourth, Kargel dedicates the latter part of his book to flights of fancy with scenarios of permanent settlement on Mars and terra-forming - which quite frankly should be confined to the realm of science fiction. Finally, it is so obvious that the book has not been properly edited. No editor would allow a science-based book to be published without adequate references between text and illustrations. Worse still, even the figure captions often don’t relate very well to what’s in the photos.

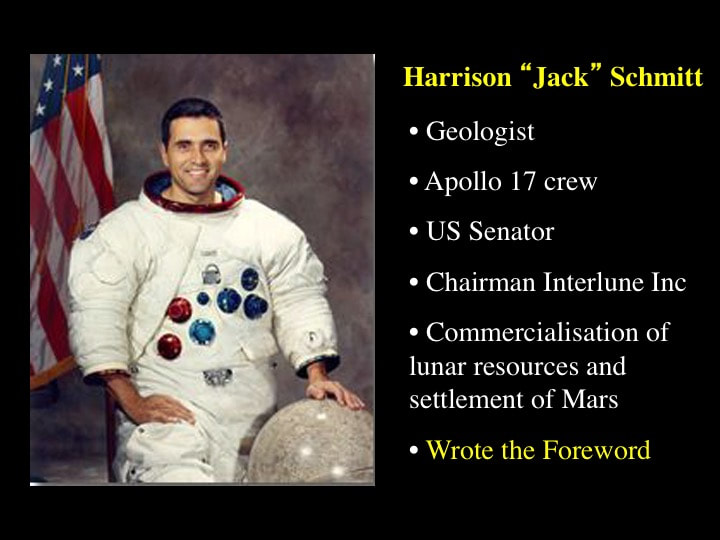

So, how did a tome of 555 pages like this get published ? Good question ! A possible answer is to be found in the foreword to this book provided by Harrison Schmitt : geologist, Apollo 17 crew member, US Senator ... and Chairman of Interlune Inc., a private venture focused on the commercialisation of lunar resources and the settlement of Mars. Interestingly the foreword makes no reference whatsoever to Kargel’s book, or even to its content ! Oh, it talks about Martian geology alright - the formation of the rocky planets and the origins of their contained water - but it could be the preface to any book on Mars. However, it does contain a full one page pitch for Interlune Inc - and its business rationale. Am I being too cynical if I see a non-scientific business relationship here between Kargel, Harrison and the publishing house ? Maybe ! Whatever, I cannot recommend that you buy this book. Get your library to order it and leaf through it - speed read the text, ponder the photos – many of them ARE fascinating - jot down their code numbers and go and find them on the web like I did.

On the other hand, if you want a really good read about the planetary geology of Mars, including a well illustrated discussion of water, oceans, rivers and glaciation, I can strongly recommend Bill Hartmann’s book “A Traveler's Guide to Mars” that I reviewed here a year or so ago.

Happy Reading on cloudy nights …

Happy Reading on cloudy nights …

Proudly powered by Weebly