|

A TRAVELLER'S GUIDE TO MARS - by William K. Hartmann

|

“A Traveler’s Guide to Mars: the Mysterious Landscapes of the Red Planet”, written by the well known planetary astronomer and illustrator William K. Hartmann, is an excellent book that delves into many of the geological themes that I have discussed during my presentations on Mars

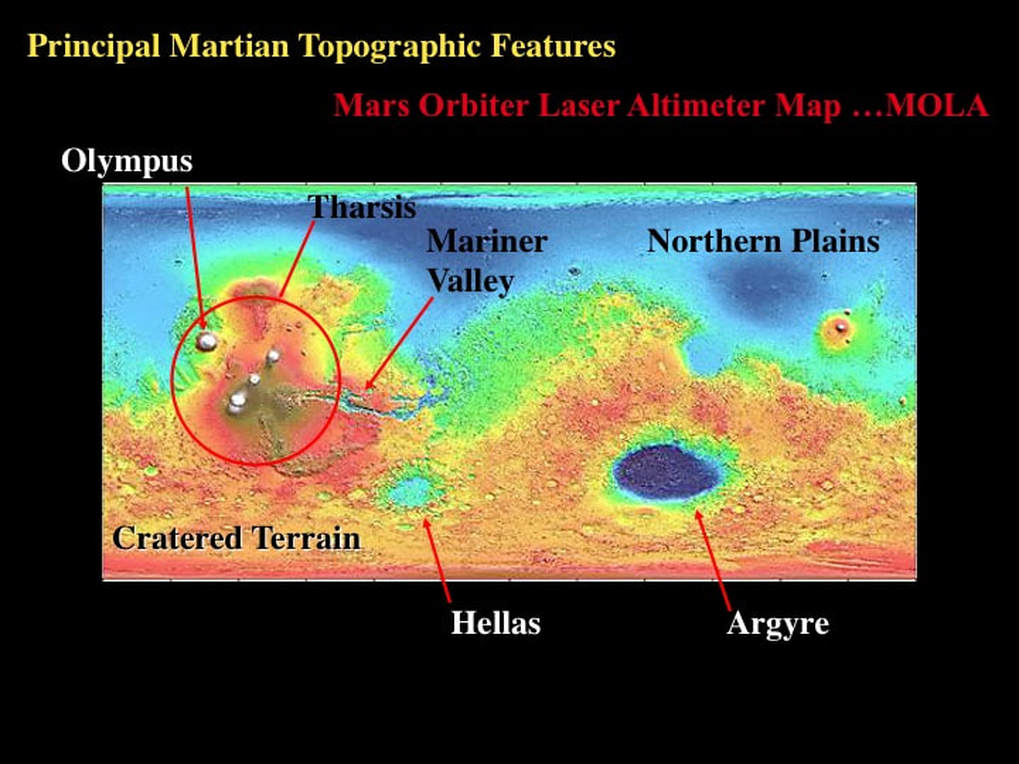

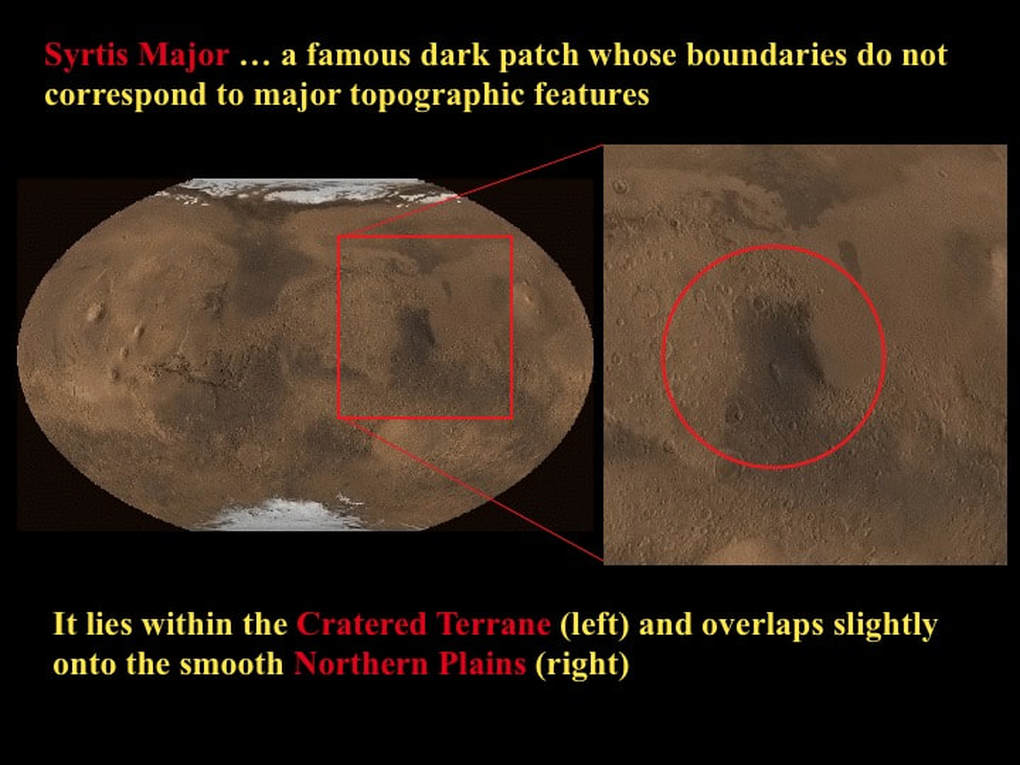

In a number of places in the book, Hartmann emphasises the point that the dark markings that we can see through telescopes, from amateur to Hubble, do not correspond to the major topographic features on Mars. He explains that the red colour is due to fine, oxidised (rusty) sand, and that the dark markings are areas where that sand has been blown away by the prevailing winds.

Perhaps the best known example of this is the famous dark patch “Syrtis Major” that sits mostly within the Heavily Cratered Highland Terrane, and overlaps onto the smooth Plains. In other words, the boundaries of Syrtis Major don’t correspond with any topographic feature: it’s just a large patch of wind-scoured ground !

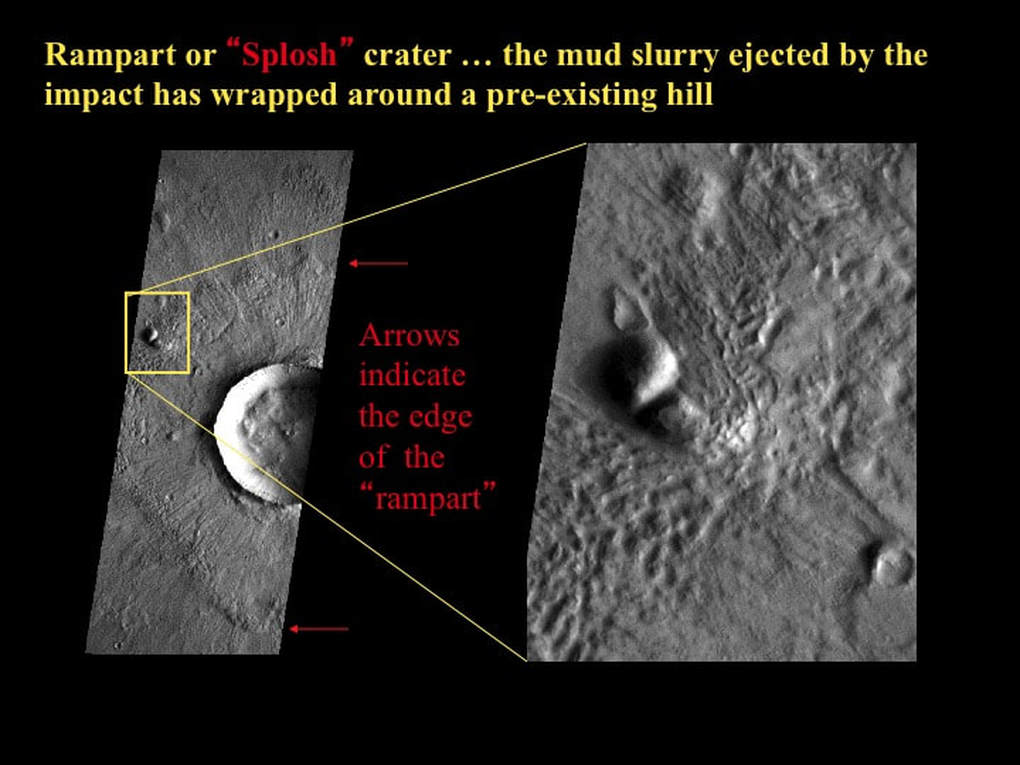

Hartmann provides extensive geological evidence and illustrations for the existence of Martian permafrost, or underground ice. In particular he shows images of a special kind of crater that formed when a meteroid impacted into ice-locked ground and converted the permafrost and its host rock into a muddy slurry that was flung out from the impact crater and draped itself around a pre-existing hill.

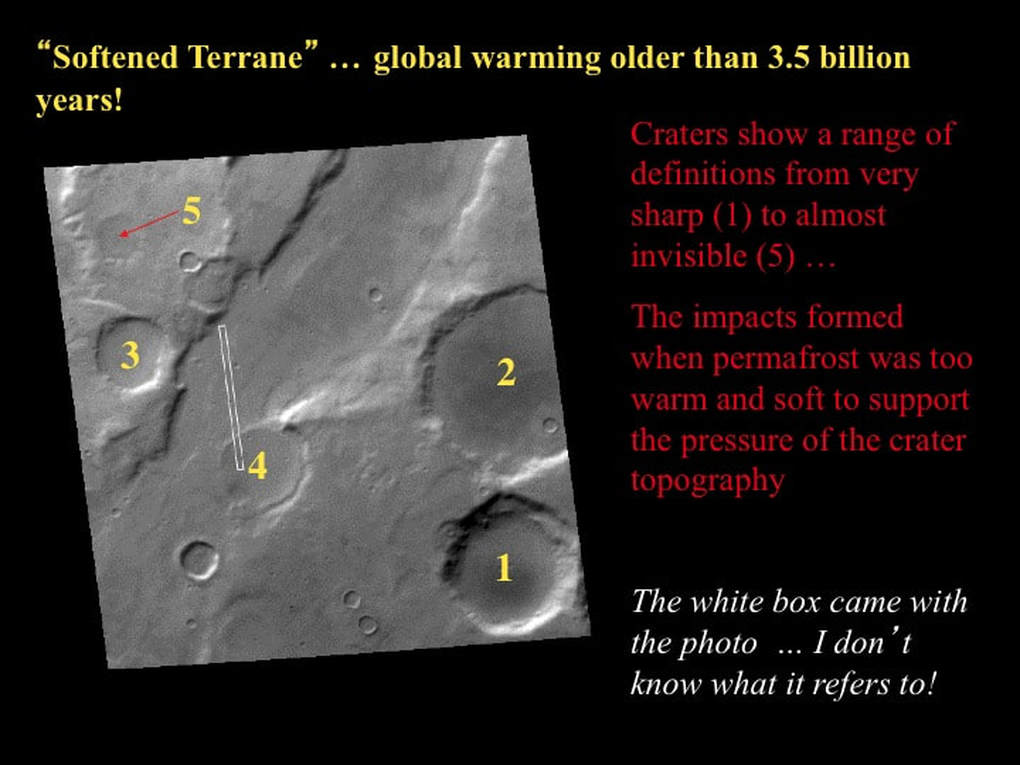

However, he also presents evidence for permafrost that I was totally unaware of: “Softened Terrane”. This is a fascinating concept built around the observation that, in some parts of Mars, what should be high walls and deep floors of relatively large impact craters are way too low, or way too shallow for their size. They look as though the crater walls have melted and sunk, and as though the crater floors have been filled in by something that is now very smooth. In fact, they look as though they were made of ice cream that had started to melt and started to flow; hence the term “Softened Terrane”. Hartmann’s explanation, supported with excellent photographs, is that these impact craters formed in ground that was underlain by permafrost that was being affected by a period of Martian global warming. He shows a series of pictures in which impact craters are in various states of definition, from really sharply defined to barely visible. It appears that older craters are less well defined, while younger ones are sharper. The interpretation is that the crater walls sank into the ground when the permafrost was warm and soft. In addition, the observation that older craters have sunk more, while younger craters have sunk progressively less, tells us that the impacts that produced the craters must have occurred while the permafrost was soft, during a period of planetary warming. What’s really fascinating is that, because the best examples of “Softened Terrane” all come from an area on Mars where cratering statistics indicate that the impacts are older than about 3.5 billion years, this means that this is evidence for a very old period of global warming, which is therefore not just a recent terrestrial phenomenon.

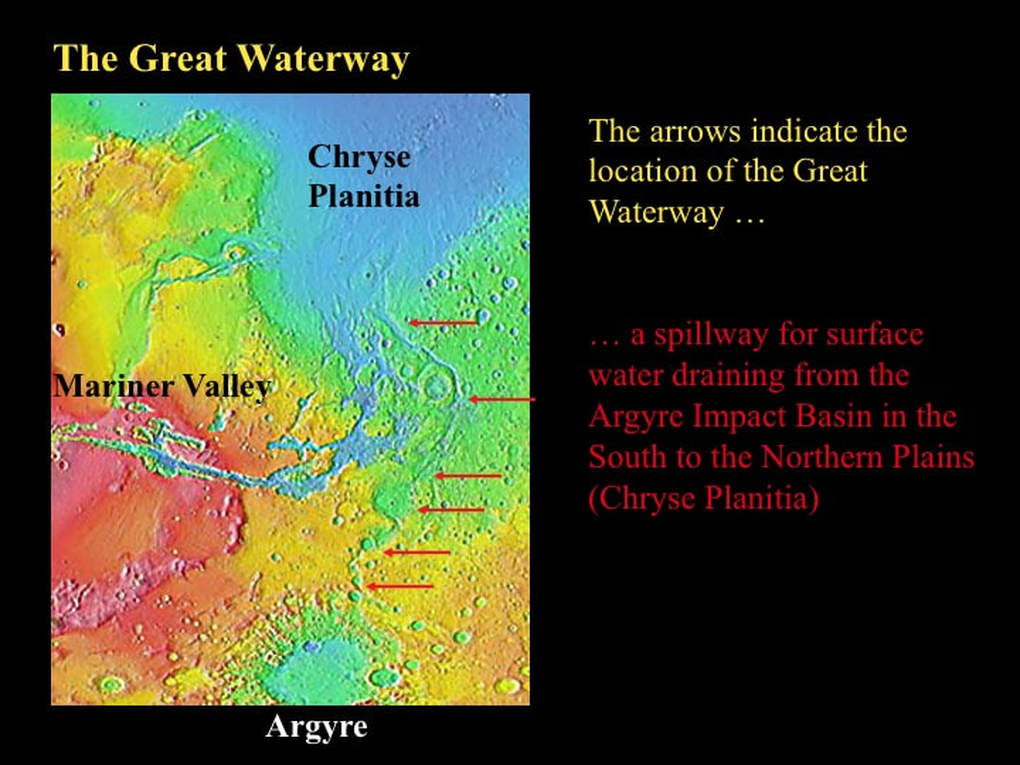

Hartmann presents evidence for what he calls “The Great Waterway” , a giant channel that connects the huge impact basin Argyre and the eastern end of the Mariner Valley where it opens out in a series of braided channels onto the Northern Plains in an area known as Chryse Planitia. The general idea is that water flowed northwards along this Great Waterway during the very early history of Mars, again more than 3.5-4.0 billion years ago, when the Martian atmosphere was dense enough to maintain free water on the planet’s surface.

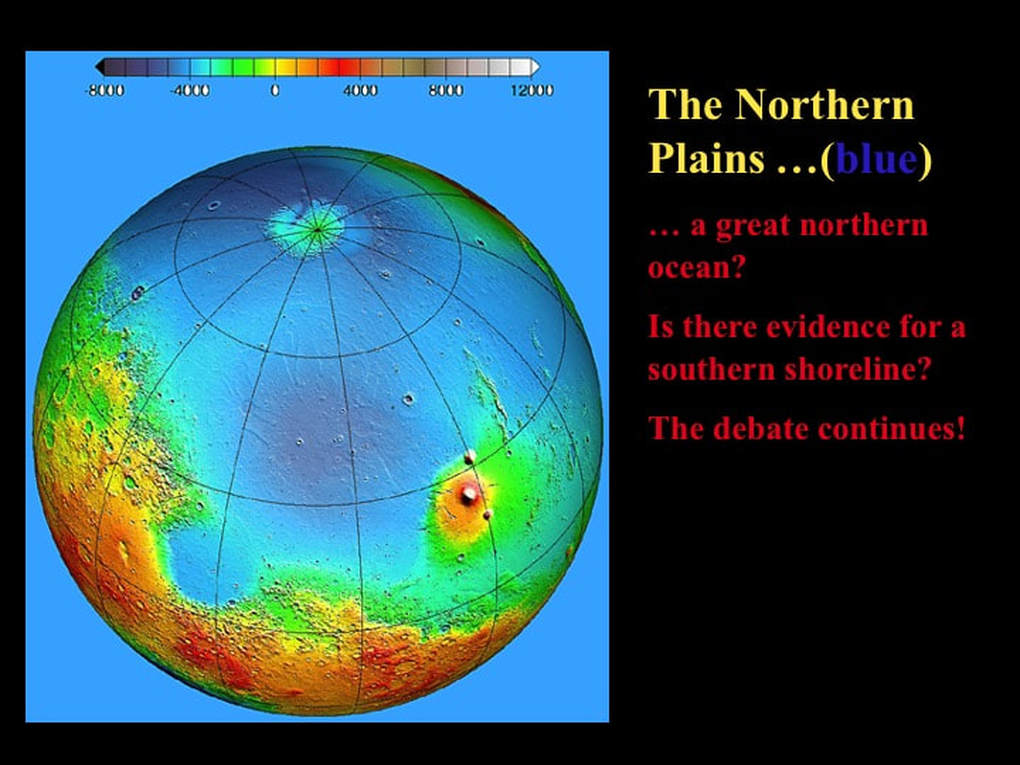

Talking of water, some have suggested that the Northern Plains could have been the floor to an ancient, long-vanished northern Martian Ocean. Hartmann presents the pro’s and con’s of the still unresolved debate regarding a possible southern shoreline to that ocean. He even has a photo of a possible sea cliff surrounding a possible bay in the possible coastline. I found this to be one of the most fascinating parts of the book !

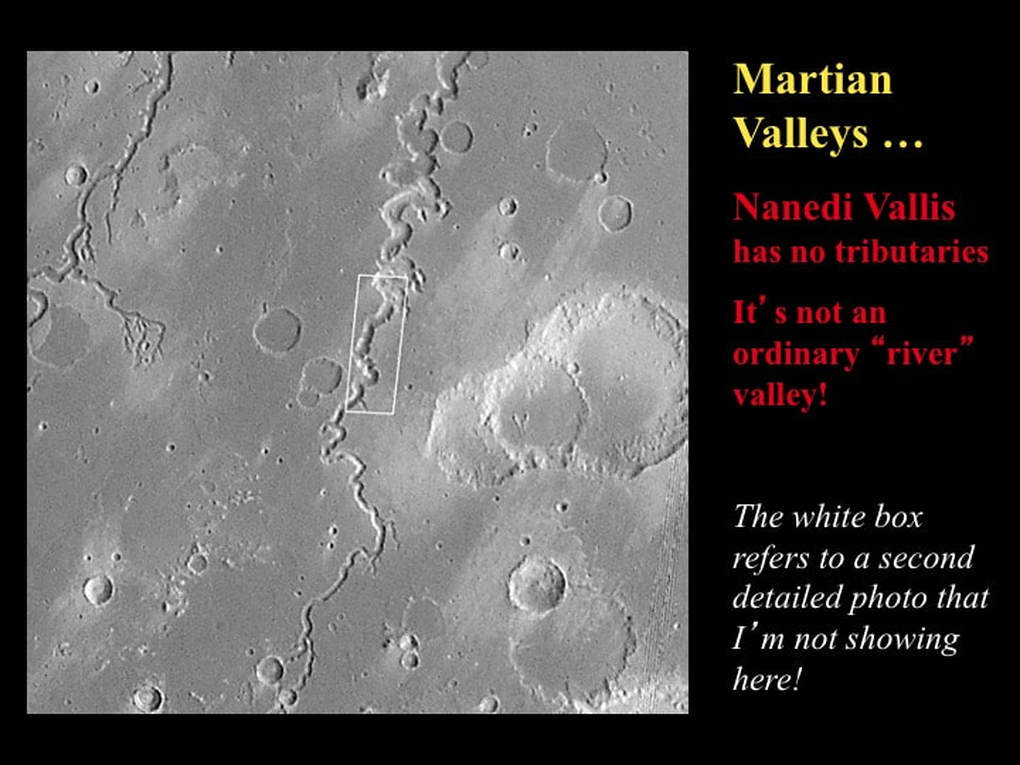

Mars has lots of valleys, and Hartmann dedicates a significant section of the book to them. He presents an excellent detailed discussion of the evidence for flowing surface water in various river beds that would have emptied into Chryse Planitia at the eastern end of the Mariner Valley. In particular, he presents the valleys Nanedi Vallis and Nirgal Vallis that lie North and South of the east end of the Mariner Valley, respectively. These valleys are strange because, although they meander like rivers here on Earth, they have no tributaries. Hence the question is, where did the water that carved them come from? This has led some planetary geologists to conclude that, while there may be some evidence for surface water having flowed within these valleys at some stage, the valleys themselves resulted from the release of local groundwater. Surprisingly, despite the fact that there are no equivalents to these valleys on Earth, Hartmann glosses over this and treats the Martian features as normal river valleys.

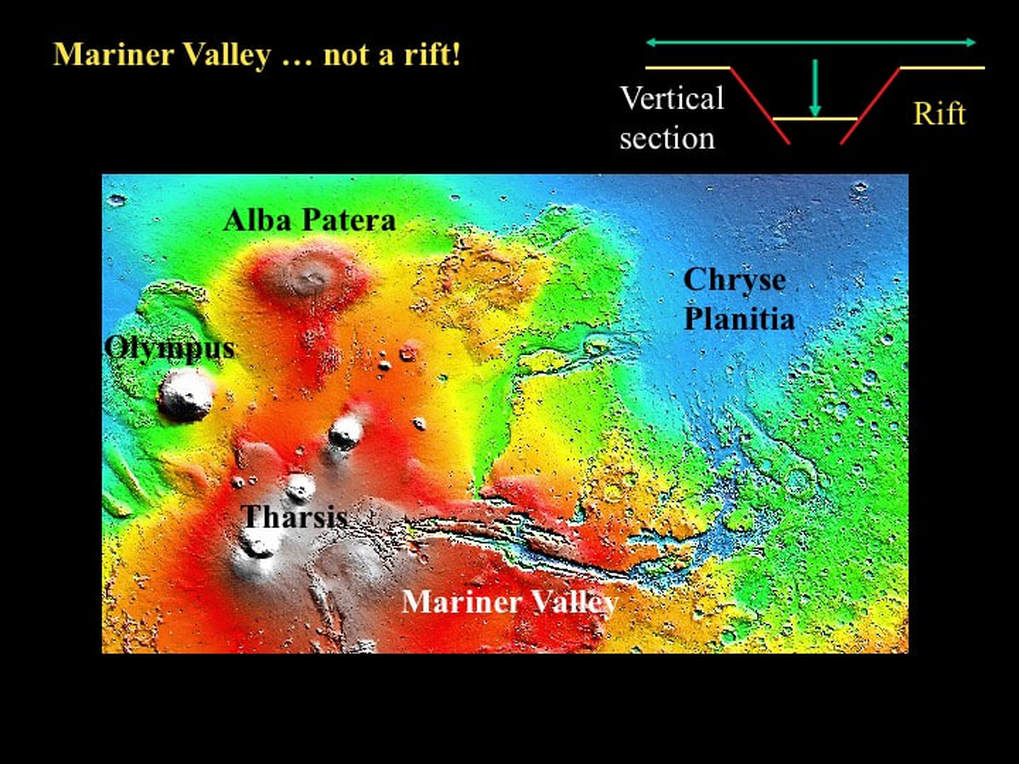

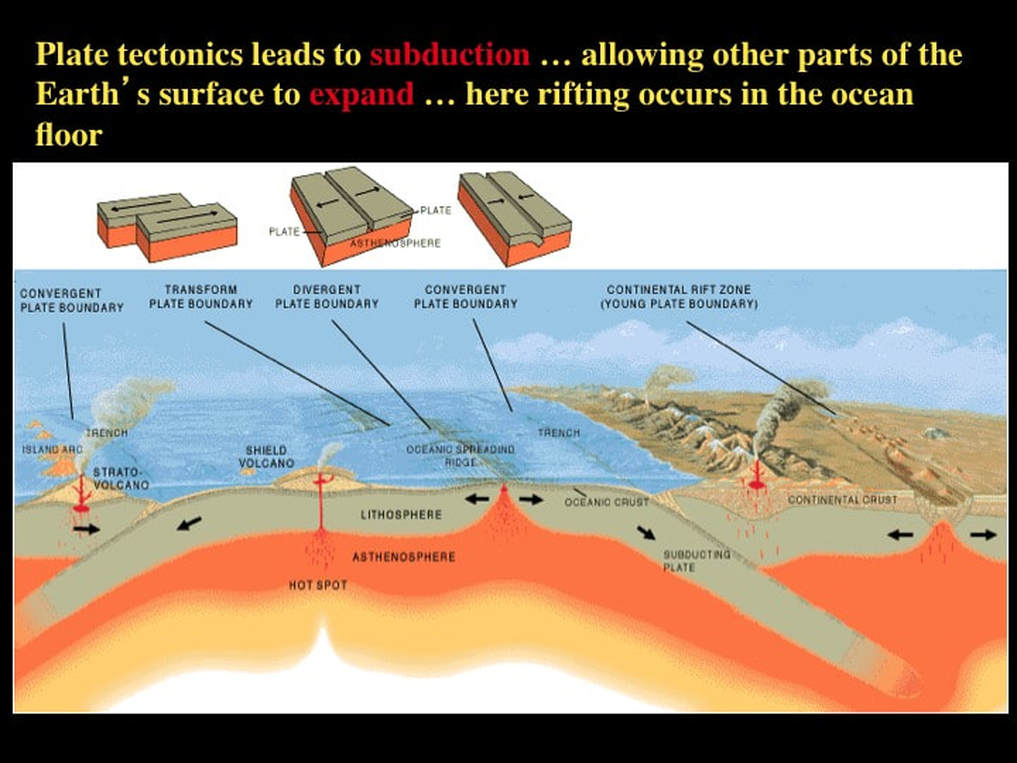

On the subject of Valleys, the Mariner Valley is the longest and largest valley in the entire Solar System. On Earth, it would stretch right across the whole width of the US! Some have described this as a rift valley, but as we know from the Ottawa Valley where we live, in order for a rift to form the valley walls must move away from each other, across the valley trend, in order to allow the valley floor to drop down. That means that the planet has to make room for the valley to widen.

On Earth, this is possible because of Plate Tectonics where the plates of the Earth’s outer layers can move sideways. But there’s no evidence at all for Plate Tectonics on Mars, so there’s quite a debate about exactly how the Mariner Valley formed in the first place.

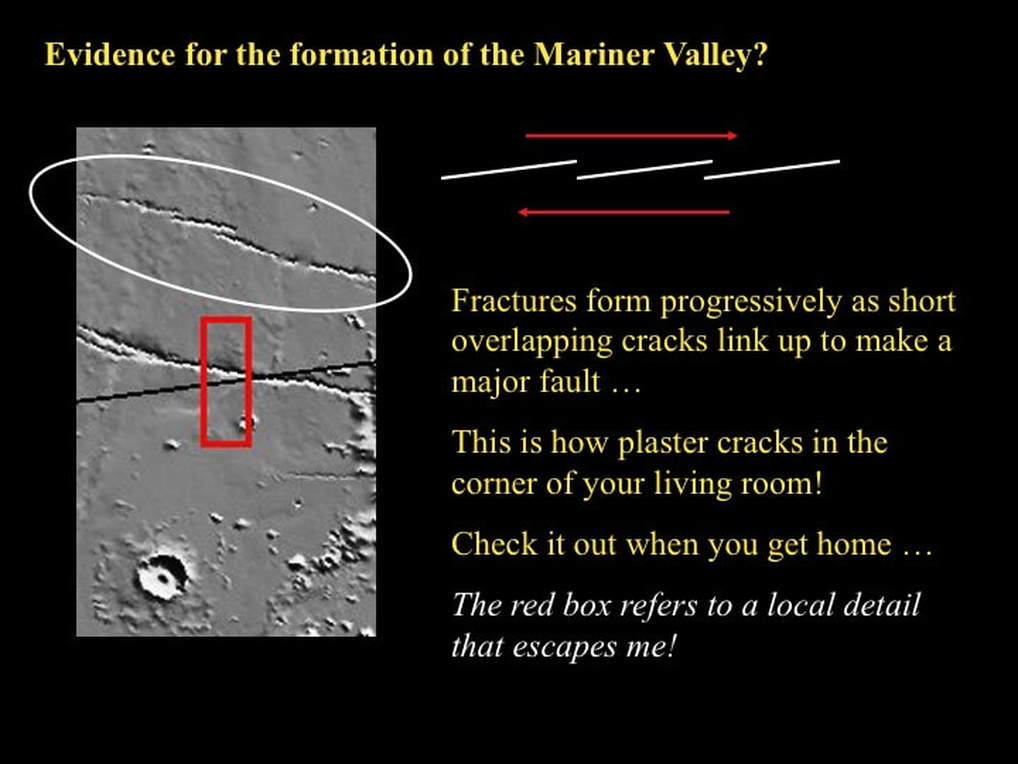

My preferred interpretation, that I alluded to in AstroNotes two years ago (December, 2002), is that the Mariner Valley started as a series of fractures whose walls moved parallel to the fractures, not perpendicular to them. This would create long lines of weakness that could be exploited by massive flash floods that carved out the valley by erosion. Hartmann examines this hypothesis in detail and presents evidence for these kinds of fractures elsewhere on Mars. This for me was really exciting because I had no idea that this evidence was already available when I first wrote about this in AstroNotes !

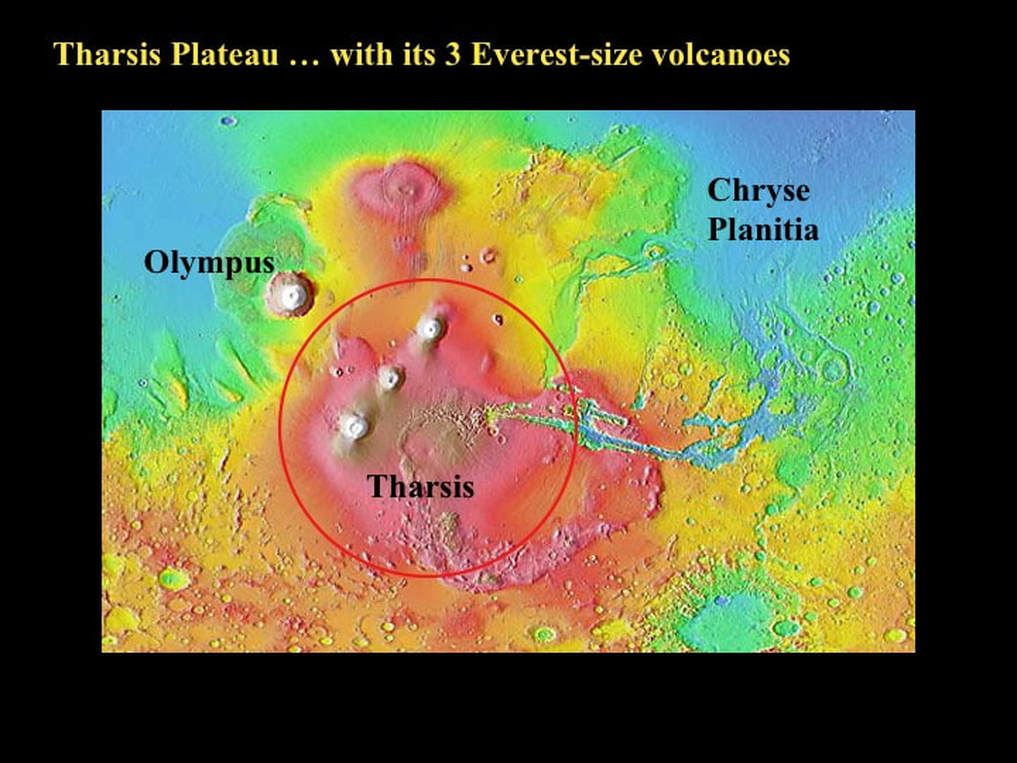

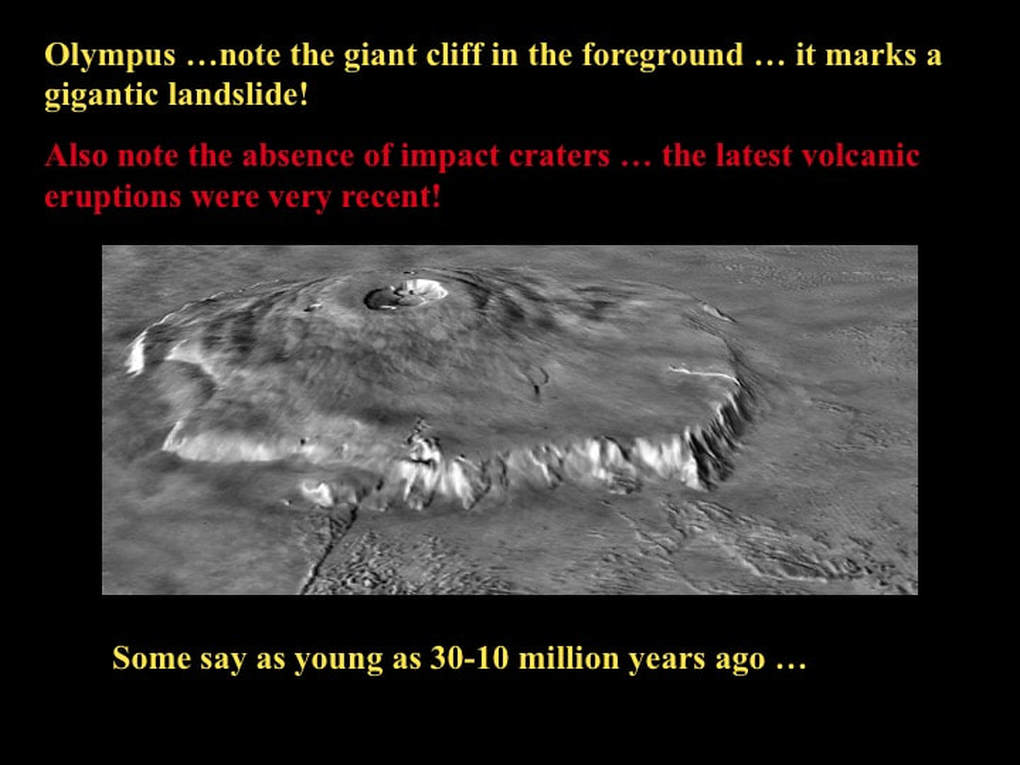

As you would expect, there is a section in the book on the Tharsis Plateau and its associated volcanoes, but only 12 pages ! This was a big surprise and a disappointment because Tharsis is the strangest geological feature in the entire Solar System; in fact it defies our understanding of planetary geology. It is as high as the highest plateau on Earth, the Tibetan Plateau north of the Himalayas, and it is capped by three giant volcanoes, each one as high again as Everest !! The strange thing about Tharsis and its volcanoes is that it’s the only major volcanic centre on Mars, and it has been active in the same place for almost 4.0 Ga !!

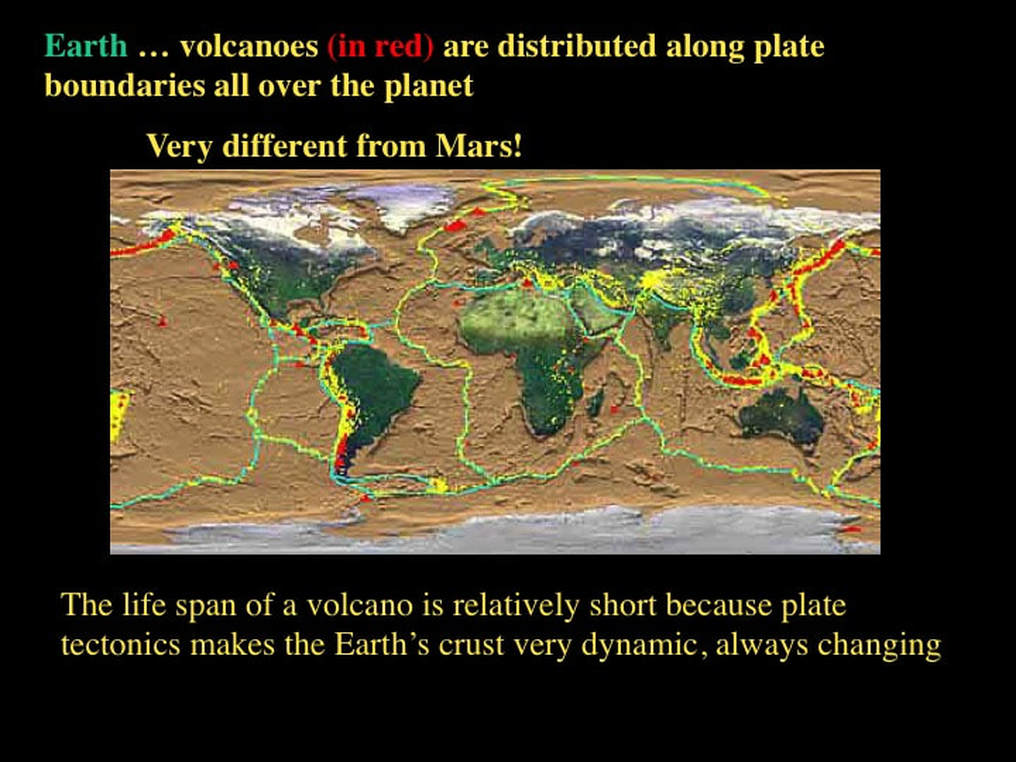

The strange thing about Tharsis and its volcanoes is that it’s the only major volcanic centre on Mars, and it has been active in the same place for almost 4.0 Ga !!

Compare that with Earth, where volcanism is scattered all over the globe, and only lasts a few 10’s of millions of years in any one place. But Hartmann really doesn’t do justice to this incredible geological phenomenon. In fact he doesn’t even mention how incredibly special it is, nor what it means in terms of challenging our understanding of planetary geological theory.

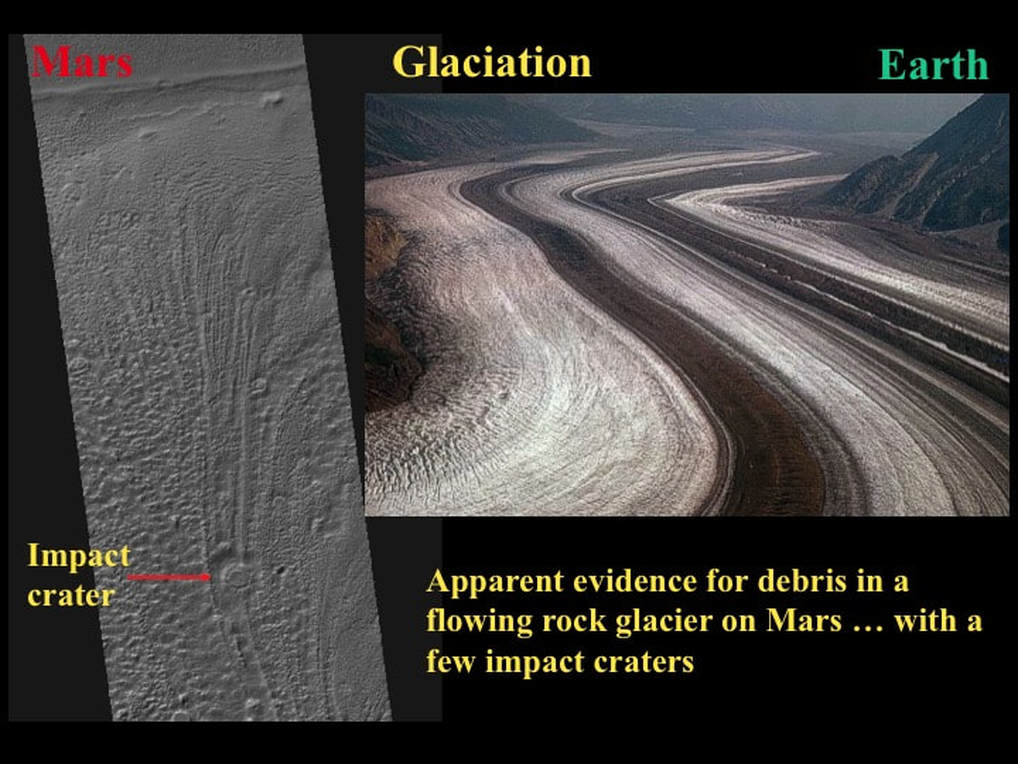

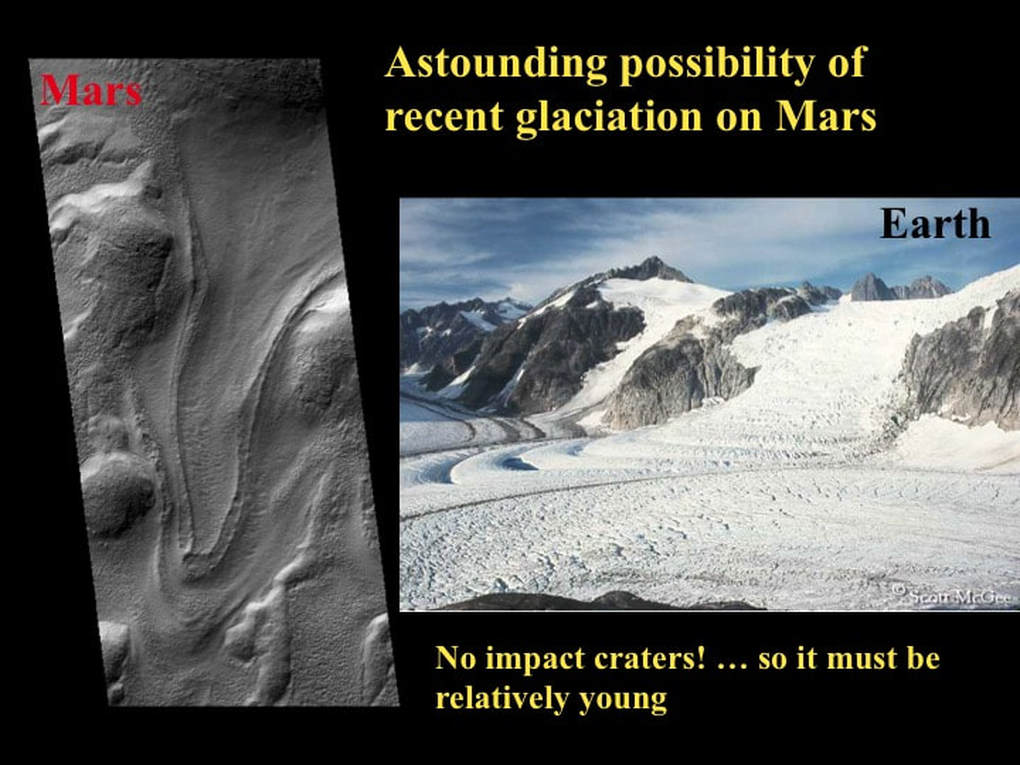

One of the most intriguing aspects of the book is the evidence Hartmann presents for glaciation, the movement of glaciers or thick ice sheets over the Martian surface.

It is impossible to do justice to this section of the book in words alone; you really have to see the photos. Suffice it to say that he presents some fascinating evidence in favour of very recent, possibly active glaciation on Mars. He certainly grabbed my attention !

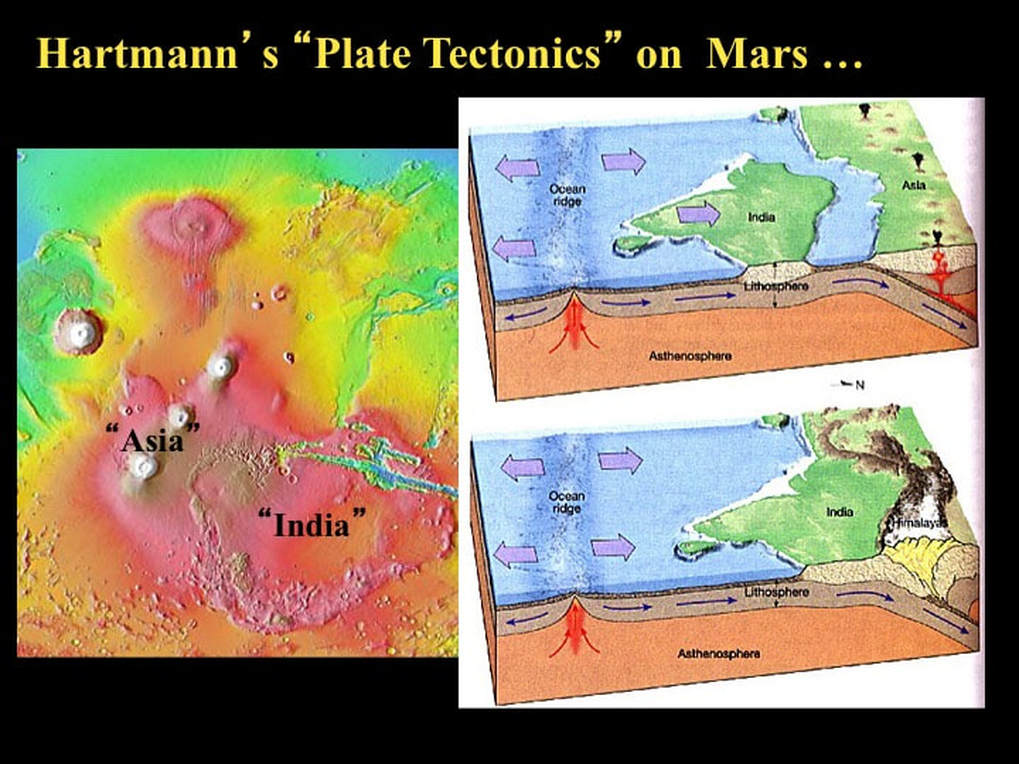

Finally, to round things off, Hartmann has an excellent section on the polar ice caps and their associated sand dune fields. However, I want to point out one very strange idea that Hartmann clearly wants to push, even if it’s only in one small part of the book. He compares the curved boundary between the Martian crust, just south of the Mariner Valley, and the Tharsis Plateau plus its volcanoes, with the Himalayas on Earth, which mark the place where India and Asia collided about 40 million years ago due to Plate Tectonics. The problem is that there is no evidence for Plate Tectonics on Mars, at any time in its history. However, the bottom line is that this, and other geological oversights, are a minor flaw in an excellent and very readable book. I’m glad it’s on my bookshelf.

Proudly powered by Weebly