|

RAPIDLY EVOLVING SOLAR SYSTEM SCIENCE

|

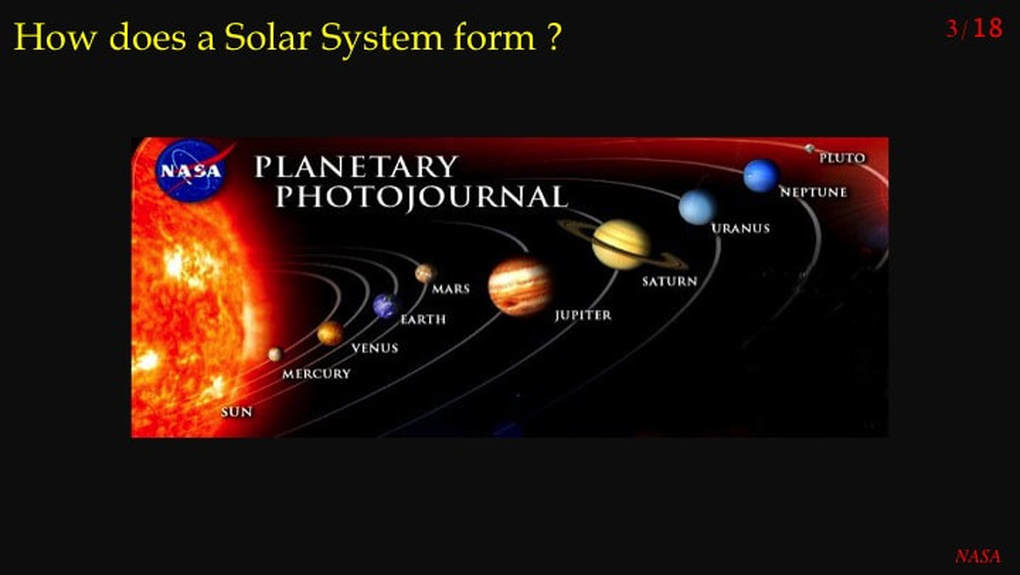

As I’ve said many times : it’s a great time to be an amateur astronomer, especially if you’re interested in our Solar System. All of the major national Space Agencies are heavily invested in studying our astronomical backyard, and some have been at it for the past two decades or more. The abundance of observations is sometimes overwhelming : think Saturn, Mars, Mercury and Pluto - and that’s just the recent headliners. However, beyond observing and measuring what’s visible to the eye or geophysically detectable, scientists and amateurs alike are keen to understand the origins of our Solar System : how it started, how it initially evolved - in short, how did it happen ? Why do we want to know this ? Because (1) we now know that our Solar System is not alone, and we want to be able to compare it with the 1000s of other planetary systems that we are discovering elsewhere in our galaxy; and (2) because the origins of our Solar System started at ~4.65 Ga ago, hence we can’t simply observe directly how things happened way back then. We need to take our observations and measurements of what we see today and stuff them into computer models, see what pops out, and ask ourselves how realistic those results are. There’s a lot of variables that go into the astrophysical calculations the models are made of, and little of what comes out from the models is “black and white”. There are always different schools of thought with different points of view, and even within a given school we’re commonly told that it could be this or that, but we’re not sure. So where does that leave us as amateur astronomers ? Well, things are looking up ! The story as it sits today is getting pretty complicated, but at the same time some of the gaping and confusing holes in the earlier, simpler stories are being filled in. In short, as the professionals work their way through their increasingly sophisticated models, they are making progressively more sense.

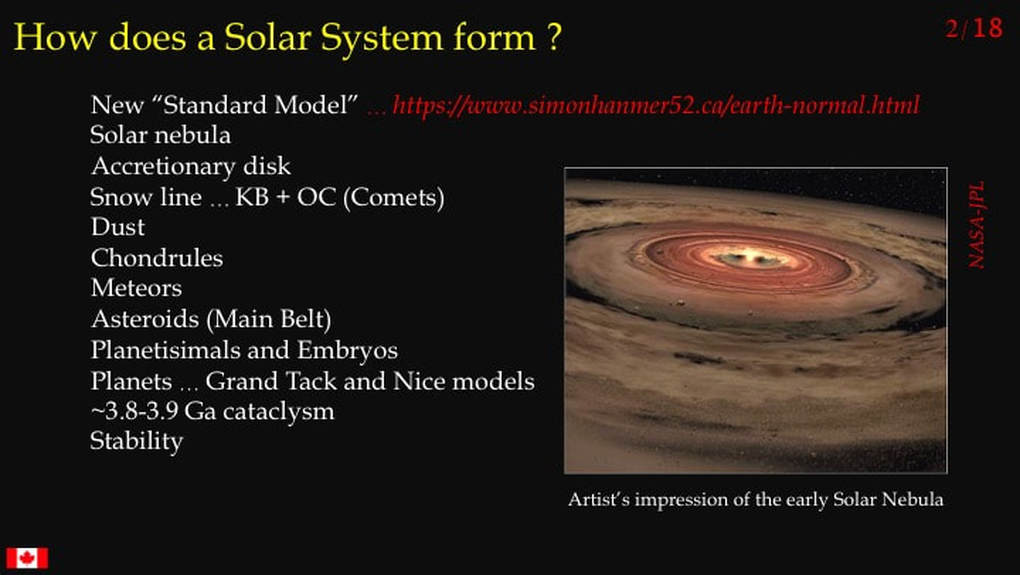

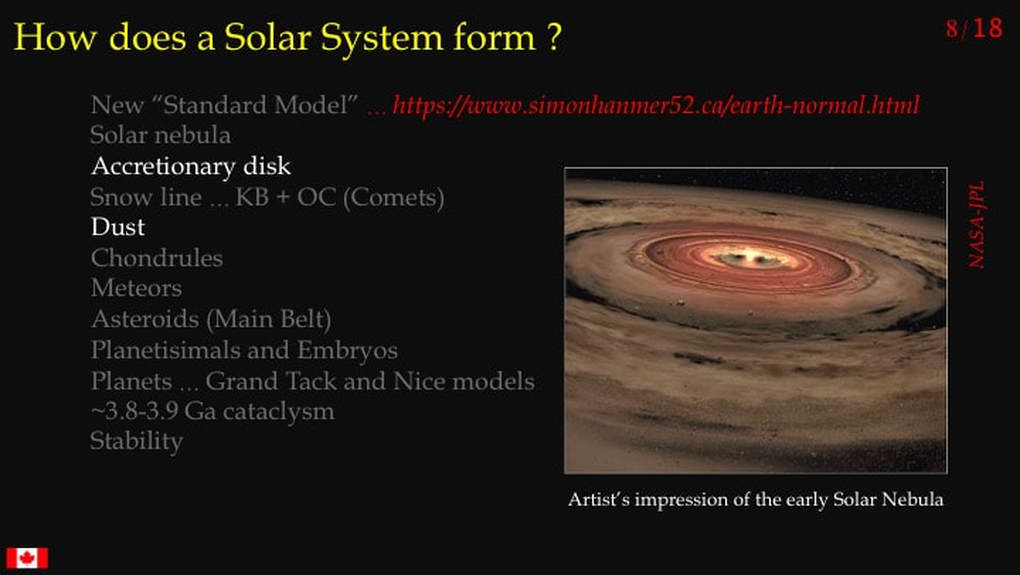

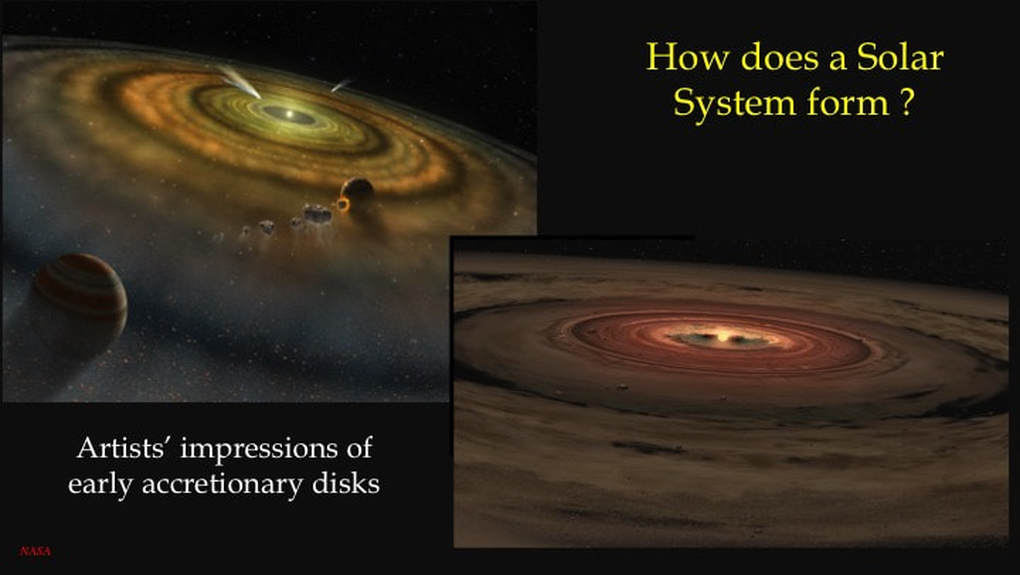

I want to start by looking at the origins of the Solar System : what do we think we already know, and what new questions are planetary astrophysicists currently asking themselves ? Let’s start with a overview of what has become the currently leading model developed over the past 15 or so years, or to put it bluntly, what has come to be the new “standard model” . In the beginning was the Solar Nebula a cloud of interstellar gas and dust that collapsed by self-gravitation and began to spin. A spinning, collapsing cloud turns into a spinning accretionary disk within which a central star (the Sun) and its attendant planets form by accretion of the gas and dust - and this business of planetary accretion is one of the major headaches facing astrophysicists today. The accretionary disk is hotter in the inner part, cooler in the outer parts and divided by what’s called a “Snow Line”. Water can exist outside of the Snow Line, but gets driven outwards in the part of the disk between the Snow Line and the Sun.

This is why we get wet Gas and Ice Giant planets in the outer Solar System, and drier rocky or Terrestrial planets in the inner Solar System.

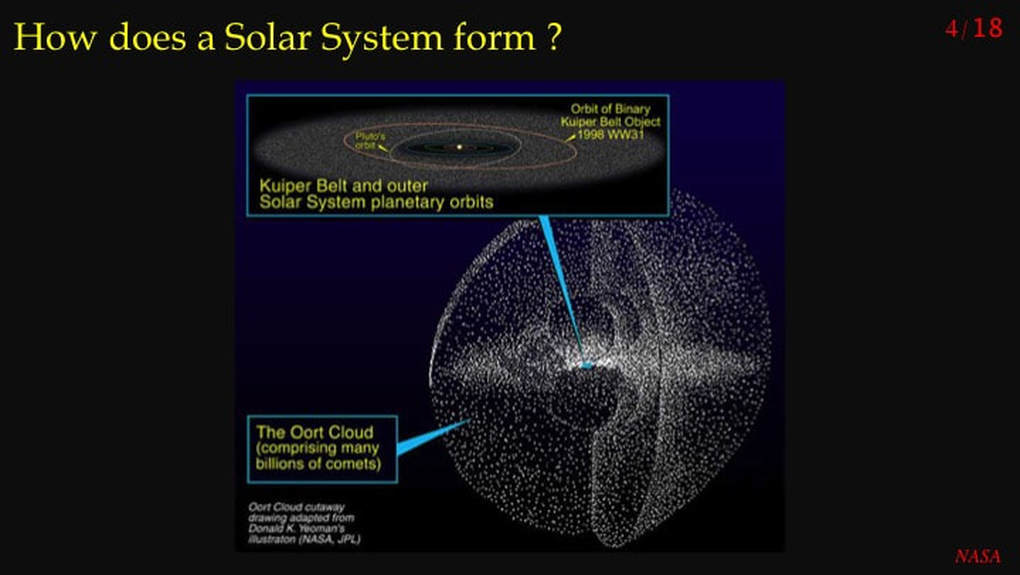

Today, what was originally the wet outer accretionary disk grades further outward into the Kuiper Belt : an outer disk that is populated by comets and icy dwarf planets, likely similar to the dwarf planet Pluto. Finally, what today we see as the planetary zone and the Kuiper Belt are enclosed by an external sphere of comet materials known as the Oort Cloud. I know of no models of the early Solar System that include an Oort cloud, so its origins remain – well – cloudy !

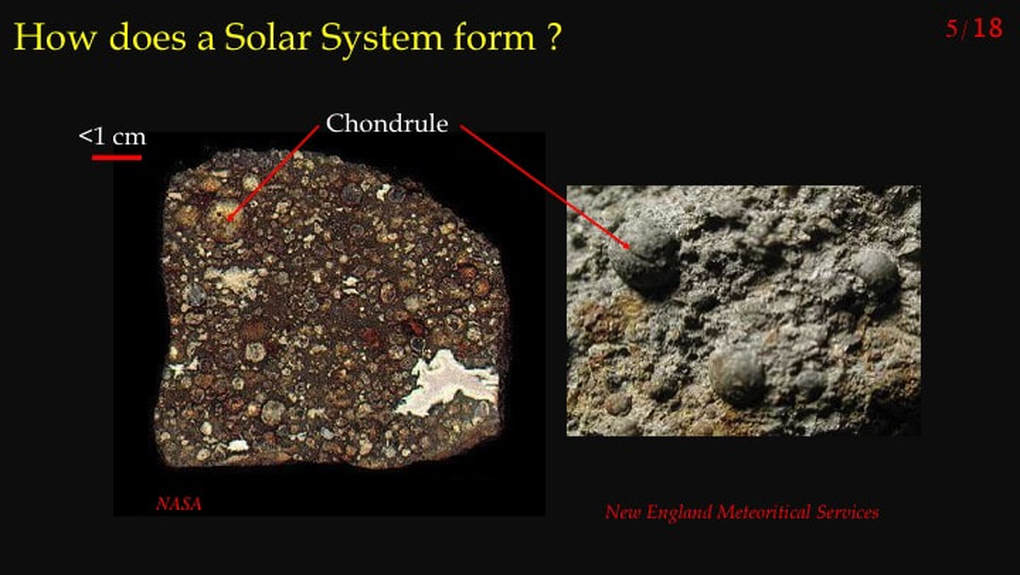

What was going on in the primeval accretionary disk ? Somehow - and that’s the operative word because there’s a great deal of debate about this that we’ll look at later - the dust turned into sand- and gravel-sized chondrules of rocky material, that clumped together to form pebble-size objects, that further clumped together to form asteroids, planetisimals, planetary embryos, and eventually planets – at least, according to the classical model.

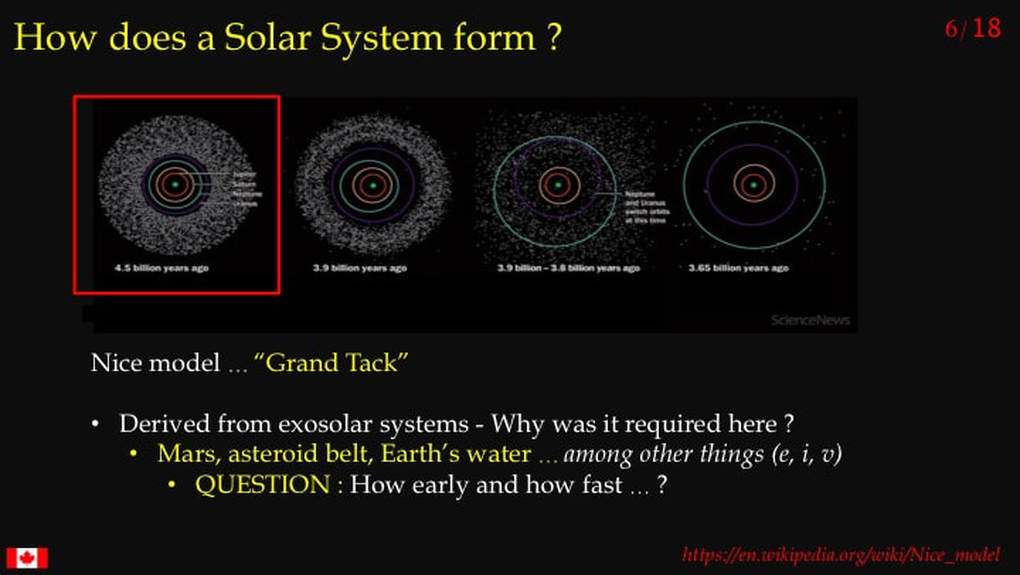

Inspired by the large number of Jupiter-size planets located in the inner parts of the planetary systems they were detecting outside of our Solar System, astrophysicists introduced the concept of giant planet migration into their Solar System models. According to what was originally known as the “Nice” model, Jupiter formed very early, and drifted inwards toward the Sun, followed by Saturn. When Saturn nearly caught up with Jupiter, the pair of Gas Giants turned around and began to migrate back outwards again in a manoeuvre known as the “Grand Tack” (the details of which don’t concern us at this point : we’ll look at them in a later talk). What happened to the rocky planets of the inner Solar System while all this migration was going on ? Well, according to the Nice / Grand Tack model they hadn’t formed yet. Given that we know that Earth formed during the first 100 Ma of Solar System history, that means giant planetary migration occurred very early.

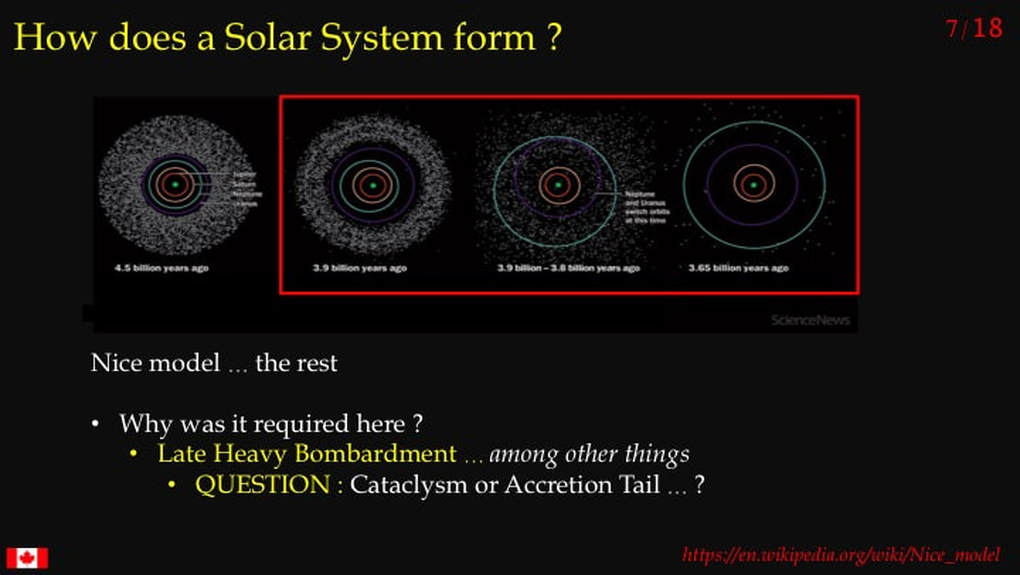

Now, here’s the next big headache confronting planetary astrophysicists. Not much happens in the model for the next 600 Ma – and that’s a long time to wait without much idea of what’s going on, hence the headache – until Jupiter and Saturn begin to gravitationally push Uranus and Neptune out and up against the Kuiper belt, at which point all hell breaks loose as Kuiper belt materials are stirred-up and hurled gravitationally into the planetary zone of the developing Solar System in what is known as the Late Heavy Bombardment that occurred at ~3.8-3.9 Ga - leaving its imprint as the massive impact basins still visible on Mercury, Mars and, of course, our own Moon. Then, in the classical model, after the Late Heavy Bombardment, accretion was pretty much over bar the shouting and our Solar System has subsisted for the past ~3.5 Ga as a stable entity. So, as you can see, the Nice / Grand Tack model is pretty much key to understanding how our Solar System formed. In fact, without Nice / Grand Tack, it’s pretty tough to explain (i) why Mars is so much smaller than Venus and the Earth, (ii) the construction of the Main Asteroid Belt between Mars and Jupiter, and (iii) the origins of water on the Earth. In addition, without the Grand Tack it ‘s difficult to explain the Late Heavy Bombardment as a cataclysmic event at ~3.8-3.9 Ga.

So we’ll take a closer look at what the Nice / Grand Tack model is, how it works, and how it produces the effects that make it seemingly indispensible in modern Solar System formation theory - but that’s a presentation all by itself, for another day.

So we’ll take a closer look at what the Nice / Grand Tack model is, how it works, and how it produces the effects that make it seemingly indispensible in modern Solar System formation theory - but that’s a presentation all by itself, for another day.

Here I want to go back to the beginnings of the accretion story : the first few millions of years after accretion began. I’d like to look at what planetary astrophysicists are saying today about how accretion began : how dust turned into particles - because it’s still a major problem.

In 2016, some of the authors of the Nice model and the “Grand Tack” published a list of the five fundamental “headaches” in understanding planet formation. Their concluding statement - “Given our lack of understanding of these issues, even the most successful formation models remain on shaky ground” - puts things in stark perspective. As the Chinese proverb would have it, the science finds itself in “interesting times”. Here, we’ll look at just the first two “headaches” : (i) what is the structure and evolution of protoplanetary – or accretionary - disks ?; and (ii) how did the first planetisimals form ? We’ll consider them together because they are intimately linked - and because there’s a great deal of debate and head-scratching today about exactly how you turn dust into planets.

Let’s start with accretion. According to classical models, dust in an accretionary disk sticks to other dust by electro-static forces. While this sounds simple enough, it turns out that dry 1mm silicate grains (SiO2 : rock-forming minerals) bounce off each other (known as the “bouncing barrier”), although beyond snow line they bounce at larger dm sizes (x100) because they’re cushioned by ice which is less rigid than silicate. However, dm size particles are big enough to be affected by drag from gas and dust in the accretionary disk, so they lose angular momentum to the gas, migrate inward toward the Sun – and speed up ! As they speed up their collisions become increasingly energetic and disruptive. In other words, they start to break up and decrease in size, which creates a major headache by putting a severe break on accretionary growth ! Even if they avoided disruption, metre-size objects migrate so fast into the Sun due to gas drag that they have no time to grow (”metre-size drift barrier”). So, how do the astrophysical models get around these bouncing and metre-size “barriers” ? Some suggest that ice and dust form fluffy, compressible particles, hence avoiding bouncing and disruption. However, this is only applicable beyond the snow line. Others resort to proposing clumping in turbulent vortices, followed by self-gravitation – especially for dry materials inside of the snow line.

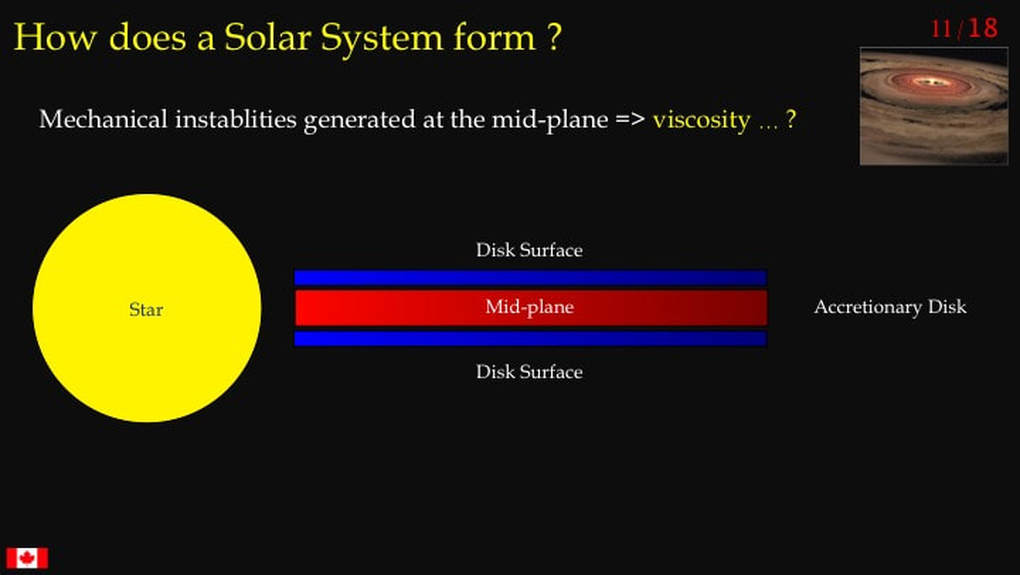

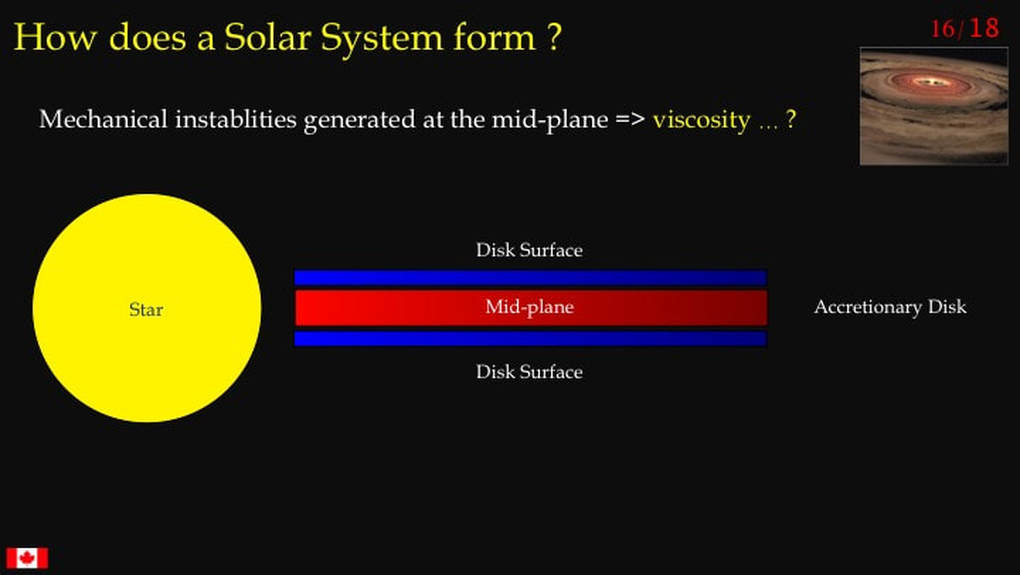

However, the question of vortices is yet another headache for planetary astrophysicists. Do turbulent vortices even exist in an accretionary disk, and if they do, how big must grains be to get caught up in them ? Some suggest that particles drift toward the accretionary disk’s mid-plane where they could generate spontaneous turbulence by forcing mid-plane gas to rotate faster than gas at the disk surfaces, presumably by an exchange of angular momentum from the particles to the gas. In short, we now have to consider the behaviour - and therefore the structure – of the accretionary disk itself in order to pursue our understanding of early particle accretion. This is going to get a bit hairy - so bear with me !

I’ve mentioned “drag”, exchange of “angular momentum” and “migration / drift” several times now. Clearly they are important for understanding the behaviour of the accretionary disk and objects within it, but what exactly do these things mean - and how do they work ? It turns out that they are all related to “viscosity”.

The accretionary disk is made of gas, dust and larger particles – all of which rub against each other. This rubbing is mediated by friction, and the friction is part of what gives the accretionary disk a viscosity. So, what is viscosity ? It’s a resistance to flow, or motion. Think “thickness” or “stiffness”of molasses vs water, where we would say molasses is more “viscous” than water. Now imagine trying to swim in molasses : its viscosity exerts a drag on your motion. Well. it turns out that a viscous disk of gas and dust will exert drag on any relatively large body trying to move through it. However, orbiting particles in a rotating viscous disk are not the same thing as you trying to swim in a pool of molasses. The rotating disk and its orbiting contents all have angular momentum ! Drag between the accretionary disk and its contained particles leads to an exchange of angular momentum, whereby particles above a certain size lose angular momentum to the gas and begin to spiral inward toward the Sun. The bigger the object, the greater the drag … and the faster the inward migration.

OK : this all sounds kind of complicated, but at least we can understand that the viscosity of the accretionary disk messes with the angular momentum of particles in the disk and causes them to migrate towards Sun, such that they speed up and have increasing problems accreting to each other to form larger bodies. However, there’s an added complication. It turns out that the viscosity of an accretionary disk is not the same throughout the disk. Worse, it can vary with time as well as place. Why ?

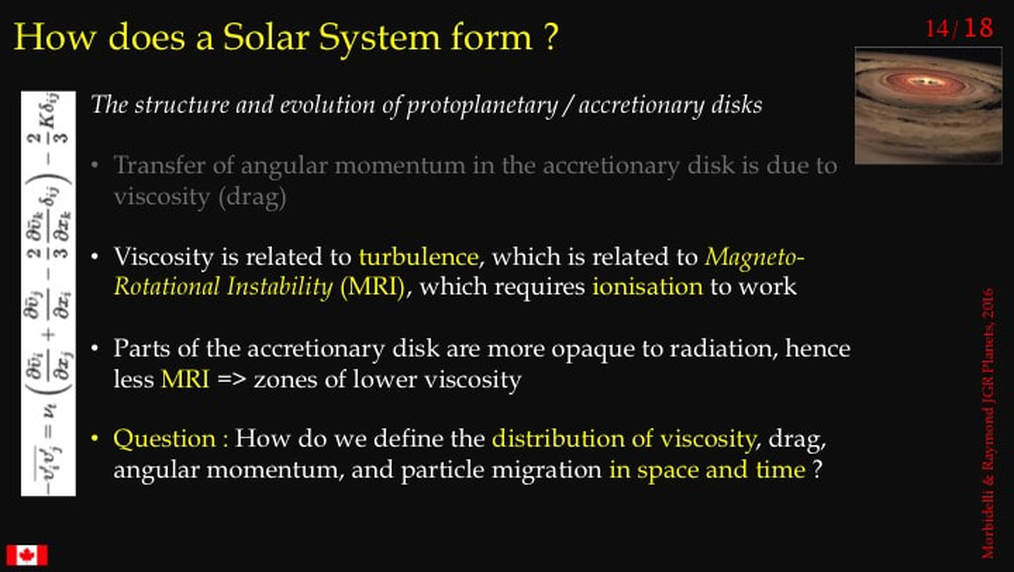

I told you that friction between gas and dust in the accretionary disk is what causes viscosity, but it’s more complicated than that.

It turns out that viscosity is also related to turbulence in the gas of the disk (yes, there’s an equation for this) – and turbulence in an accretionary disk is related to something called a Magneto-Rotational Instability ; which in simple language means localized rotation of magnetic fields. However, magnetic fields act on ionized particles : in other words atoms that have lost or gained electrons and are charged as opposed to being neutral. The commonest way to generate ionization in a disk around a young Sun is by the action of solar radiation (light, especially UV), but if parts of the accretionary disk are more opaque to the solar radiation than others then the Magneto-Rotational Instability will locally decrease – and so will viscosity. Hence the accretionary disk’s viscosity will vary locally in space and – if the opacity of the disk varies locally in time –viscosity will vary locally in time too.

How are planetary astrophysicists supposed to model the behavior and the structure of an accretionary disk and its influence over the accretion of dust, pebbles, planetisimals, planetary embryos and eventually planets if they can’t even define the distribution of viscosity, drag, angular momentum, and migration in space and time ? For a tangible every-day analogue, imagine trying to make pancakes when your batter has a spatially non-uniform viscosity that keeps changing on a 30 second time scale.

I told you that friction between gas and dust in the accretionary disk is what causes viscosity, but it’s more complicated than that.

It turns out that viscosity is also related to turbulence in the gas of the disk (yes, there’s an equation for this) – and turbulence in an accretionary disk is related to something called a Magneto-Rotational Instability ; which in simple language means localized rotation of magnetic fields. However, magnetic fields act on ionized particles : in other words atoms that have lost or gained electrons and are charged as opposed to being neutral. The commonest way to generate ionization in a disk around a young Sun is by the action of solar radiation (light, especially UV), but if parts of the accretionary disk are more opaque to the solar radiation than others then the Magneto-Rotational Instability will locally decrease – and so will viscosity. Hence the accretionary disk’s viscosity will vary locally in space and – if the opacity of the disk varies locally in time –viscosity will vary locally in time too.

How are planetary astrophysicists supposed to model the behavior and the structure of an accretionary disk and its influence over the accretion of dust, pebbles, planetisimals, planetary embryos and eventually planets if they can’t even define the distribution of viscosity, drag, angular momentum, and migration in space and time ? For a tangible every-day analogue, imagine trying to make pancakes when your batter has a spatially non-uniform viscosity that keeps changing on a 30 second time scale.

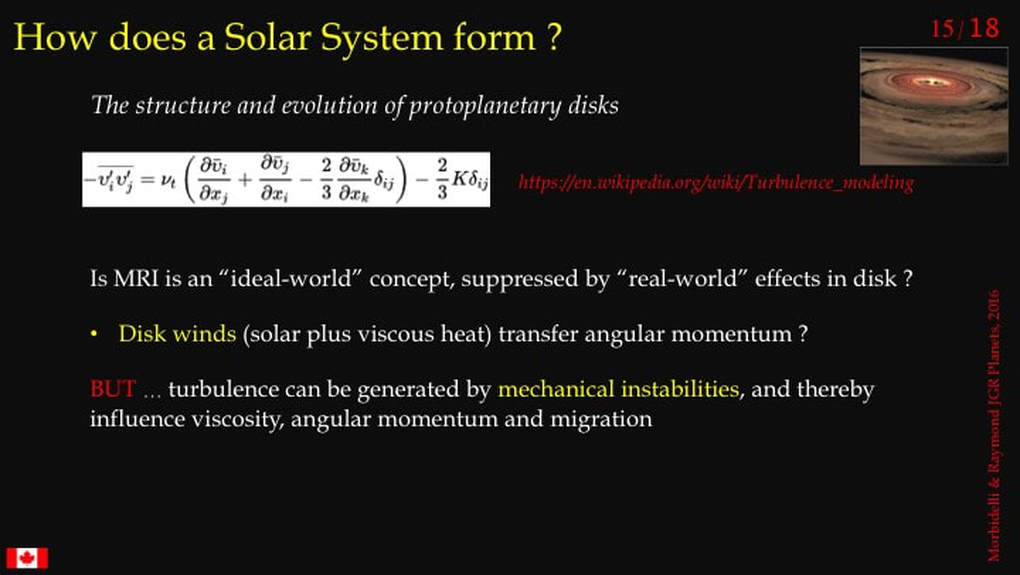

This headache has led some scientists to consider Magneto-Rotational Instability and its influence over viscosity as an “ideal-world” concept that in the “real-world” would be suppressed by what are known as Magneto-Hydrodynamic (MHD) effects in the disk - whatever those are ! Remember, the only reason we’ve been discussing viscosity at all is because it has been invoked by mainstream scientists as the primary agent for the transfer of angular momentum that then allows migration of gas, dust and particles toward the Sun, thereby controlling their ability to accrete to each other. However, what if there was another way of transferring angular momentum ? Then we could leave viscosity, turbulence and their complications out of the modeling altogether. Hence there’s a school of thought that invokes various disk winds (solar and viscous heat) to transfer angular momentum. I assume that it is carried away by the winds themselves.

However, we’re not out of the woods yet. There’s yet another school of thought that suggests that turbulence – and hence “viscosity” - can be generated by mechanical instabilities. Remember the idea I mentioned earlier of particles drifting toward the accretionary disk’s mid-plane where they generate spontaneous turbulence by forcing mid-plane gas to rotate faster than gas at the disk surfaces ?and thereby influence angular momentum and gas or particle migration ? That’s what they’re getting at here. I did warn you that there were multiple schools of thought and that nothing was “Black & White” when it comes to the early Solar System.

OK, where have we come to ? Let’s recap:

First, there is a seductive model of planetary migration to explain the origins of the planetary component of our Solar System. However, seductive or not, it has major gaps : e.g. what happened between the first 100 Ma after formation of the Sun and the Late Heavy Bombardment 600 Ma later? We’ll examine this planetary migration model and the Late Heavy Bombardment in a later presentation. For now the take-home message is that planetary astrophysicists are currently questioning when planetary migration happened, and whether there was a Late Heavy Bombardment at all.

Second, the accretionary model from dust to planets sounds good, but it is full of poorly understood steps - including multiple barriers that must be overcome before it really makes sense. The take-home message here is that planetary astrophysicists have been making enormous progress in terms of modelling, but little of this has leaked into the amateur literature. We’ll take a look at this too in yet another talk : it’s absolutely fascinating by the way !!

Third, the behaviour of the gas, dust and solid particles of all sizes - and hence their accretion in the protoplanetary disk around the early Sun - was all governed essentially by the viscosity of that disk. The take-home message here is that we have no way of knowing how that viscosity structure was distributed in space or how it evolved with time. So large-scale models of accretionary disk behaviour and structure are dramatically over-simplified. The beginnings of the accretionary process are poorly understood - and it’s something we’re just going to have to live with !

First, there is a seductive model of planetary migration to explain the origins of the planetary component of our Solar System. However, seductive or not, it has major gaps : e.g. what happened between the first 100 Ma after formation of the Sun and the Late Heavy Bombardment 600 Ma later? We’ll examine this planetary migration model and the Late Heavy Bombardment in a later presentation. For now the take-home message is that planetary astrophysicists are currently questioning when planetary migration happened, and whether there was a Late Heavy Bombardment at all.

Second, the accretionary model from dust to planets sounds good, but it is full of poorly understood steps - including multiple barriers that must be overcome before it really makes sense. The take-home message here is that planetary astrophysicists have been making enormous progress in terms of modelling, but little of this has leaked into the amateur literature. We’ll take a look at this too in yet another talk : it’s absolutely fascinating by the way !!

Third, the behaviour of the gas, dust and solid particles of all sizes - and hence their accretion in the protoplanetary disk around the early Sun - was all governed essentially by the viscosity of that disk. The take-home message here is that we have no way of knowing how that viscosity structure was distributed in space or how it evolved with time. So large-scale models of accretionary disk behaviour and structure are dramatically over-simplified. The beginnings of the accretionary process are poorly understood - and it’s something we’re just going to have to live with !

Proudly powered by Weebly