|

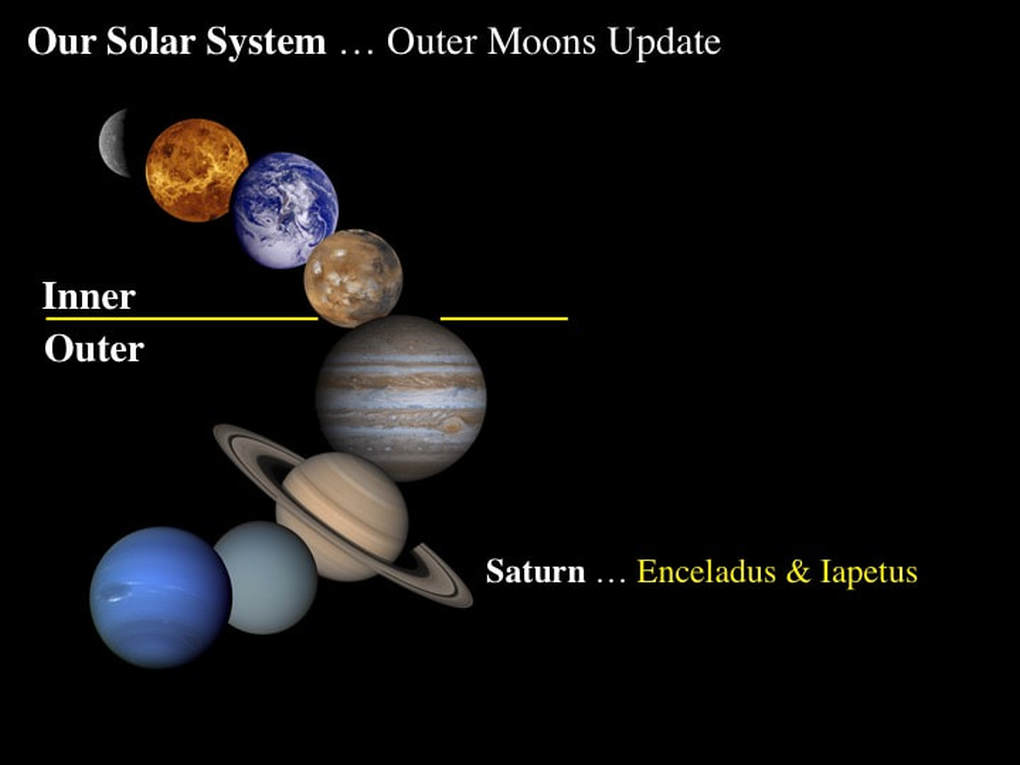

OUTER MOONS

|

Two years or so ago, I discussed with you the "geology" of the moons of the Outer Solar System. I use the word "geology", but you'll recall that - except for Jupiter's Io - the surfaces of these moons are made of ice. More recently - during the first few months of 2010 - a number of scientific papers have been published that shed new light on the origins and histories of several of the moons associated with Saturn and Jupiter, some of which you can observe for yourselves with a modest telescope. Here, I want to update you on recent thinking regarding some of these moons, starting with Enceladus and Iapetus in orbit around Saturn.

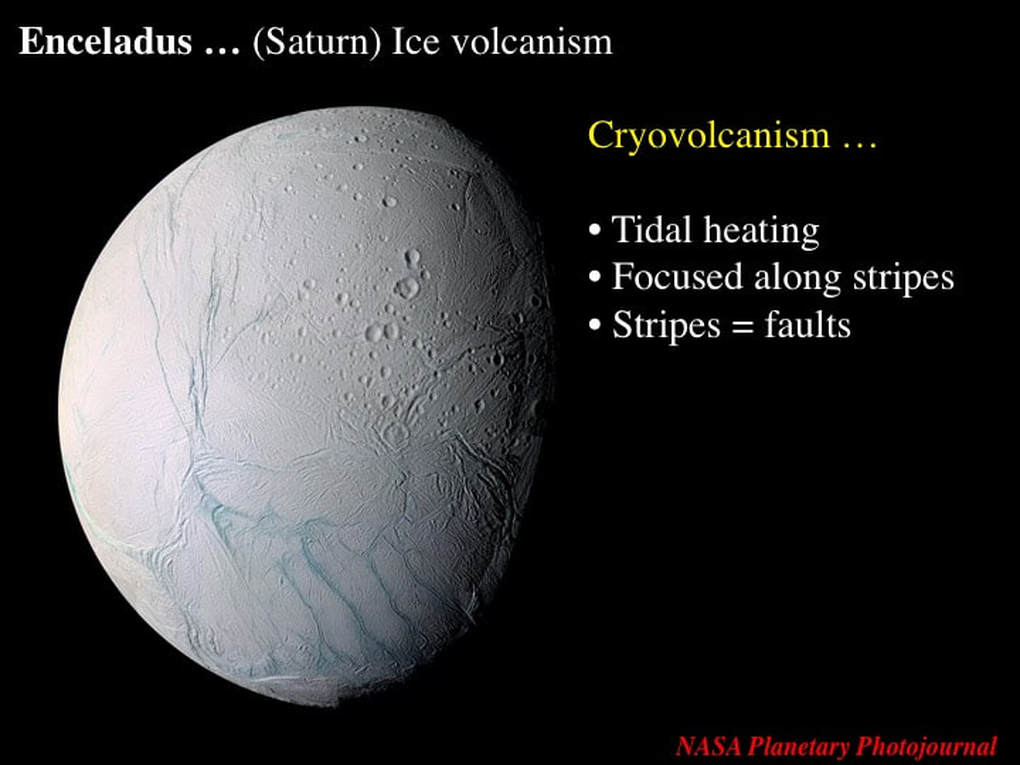

You're probably aware that Enceladus,a relatively small moon, 500km in diameter, is remarkably active with plumes of water vapour and ice crystals being ejected from fractures known as "Tiger Stripes", that show up as blue streaks in the moon's southern hemisphere in this image. This activity on an ice moon is the equivalent of volcanism on a rocky planet - referred to technically as "cryovolcanism" - and the "Tiger Stripes" are geological faults.

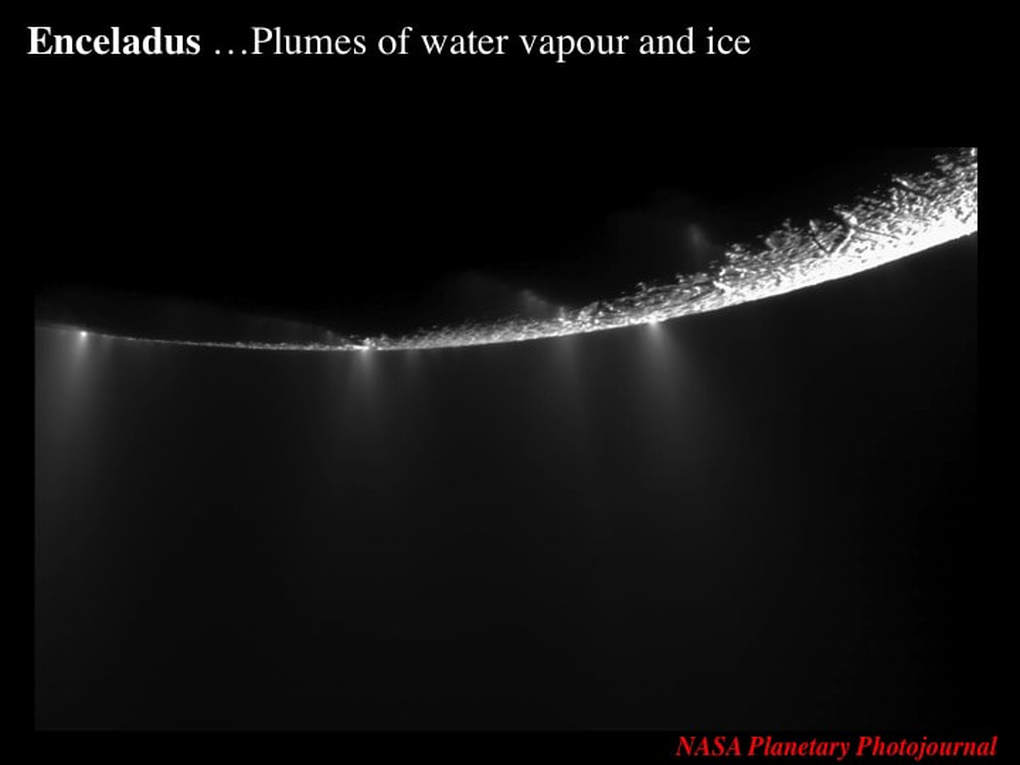

These icy volcanic plumes are pretty spectacular, as witnessed by this amazing recent Cassini image …

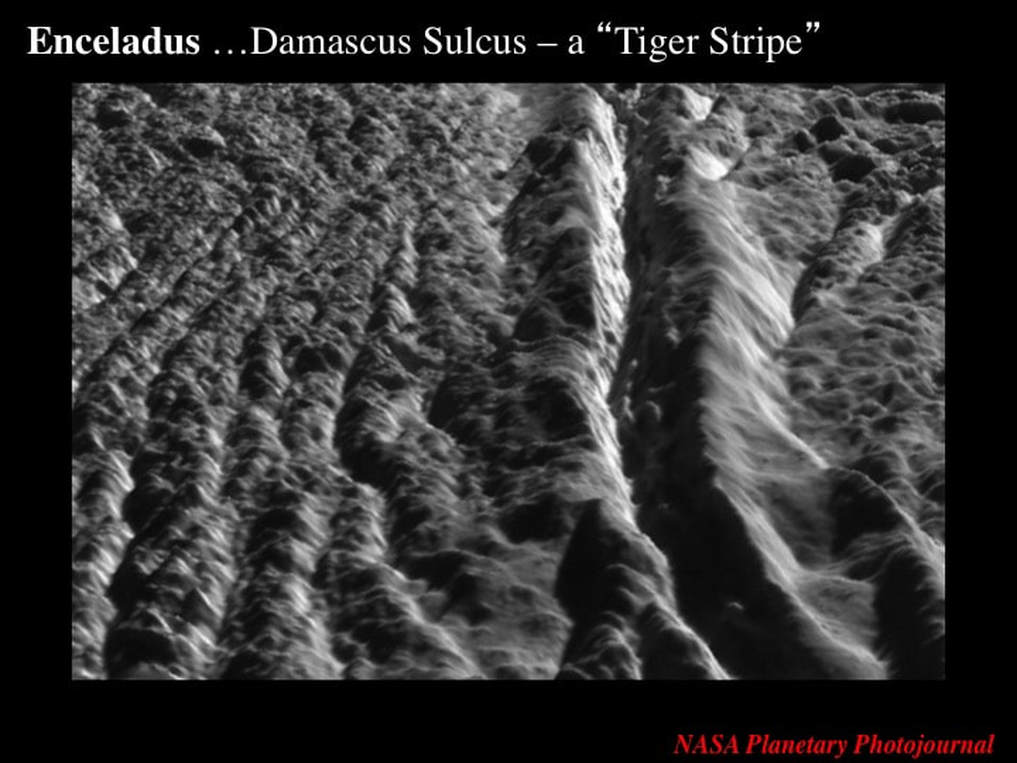

... and this spectacular close-up of where they come from - the 'V'-shaped valley on the right. Remember, everything in this image is ice !

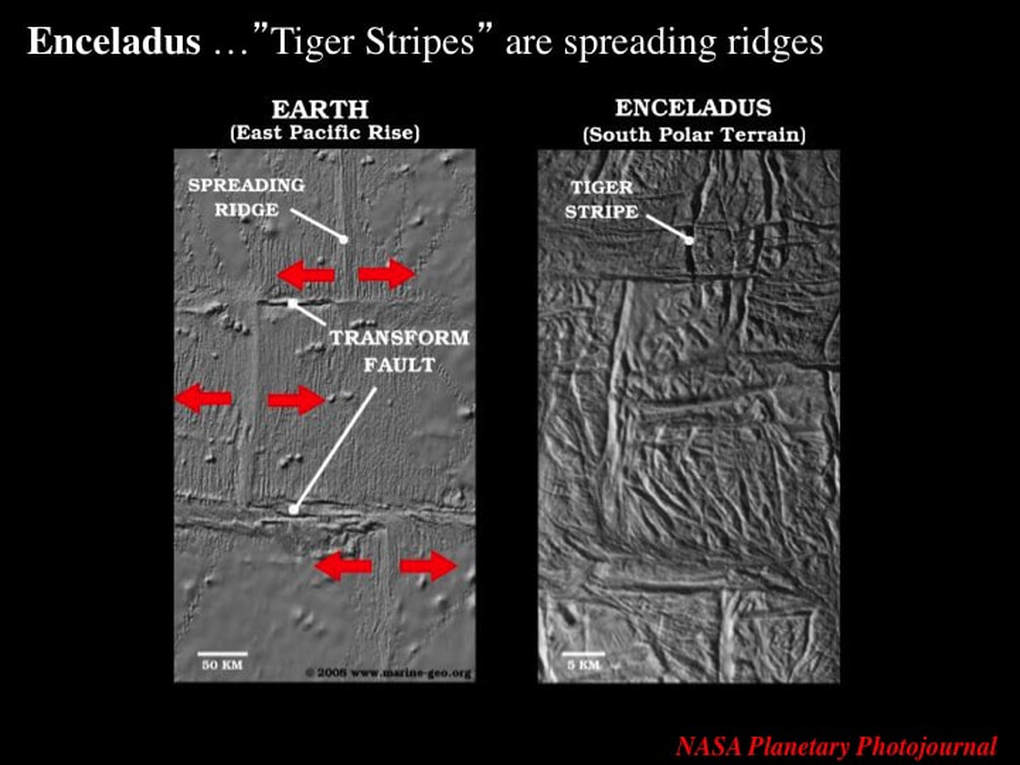

Recently, a number of planetary geologists have suggested that the "Tiger Stripes" are not just any old geological faults : they're very similar to the "spreading ridges" on Earth that gave rise to Earth's ocean floors. If you look at these images from Earth (left) and Enceladus (right) you can see why. Remember, one of these images captures part of a rocky planet, while the other illustrates an ice moon !

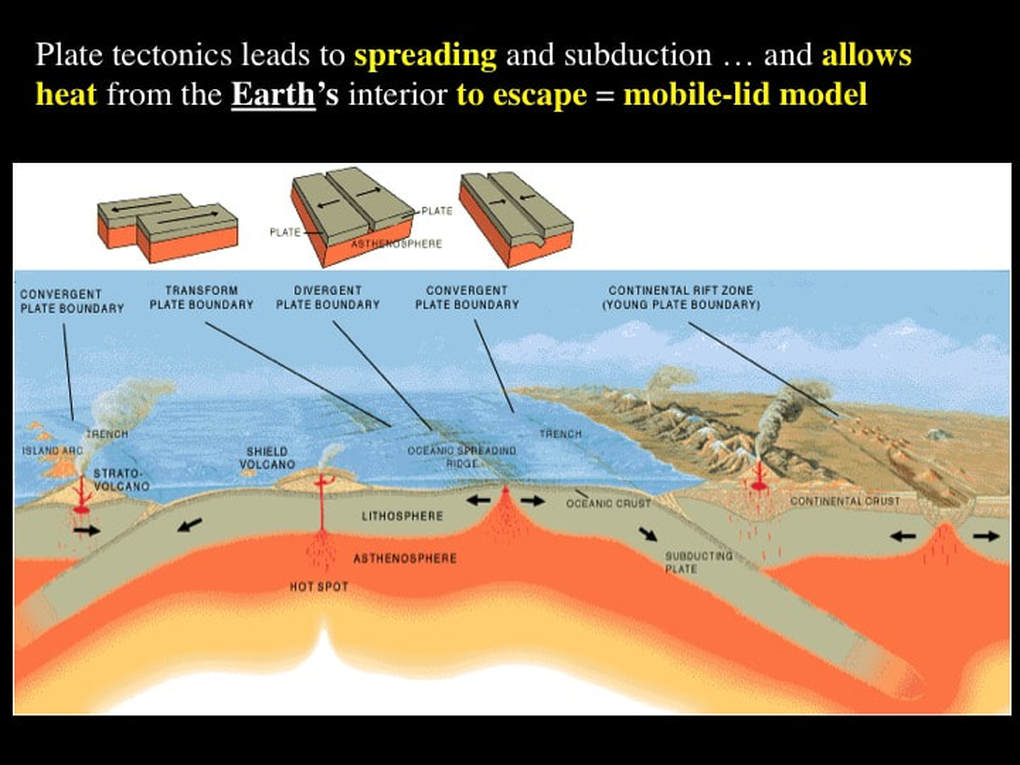

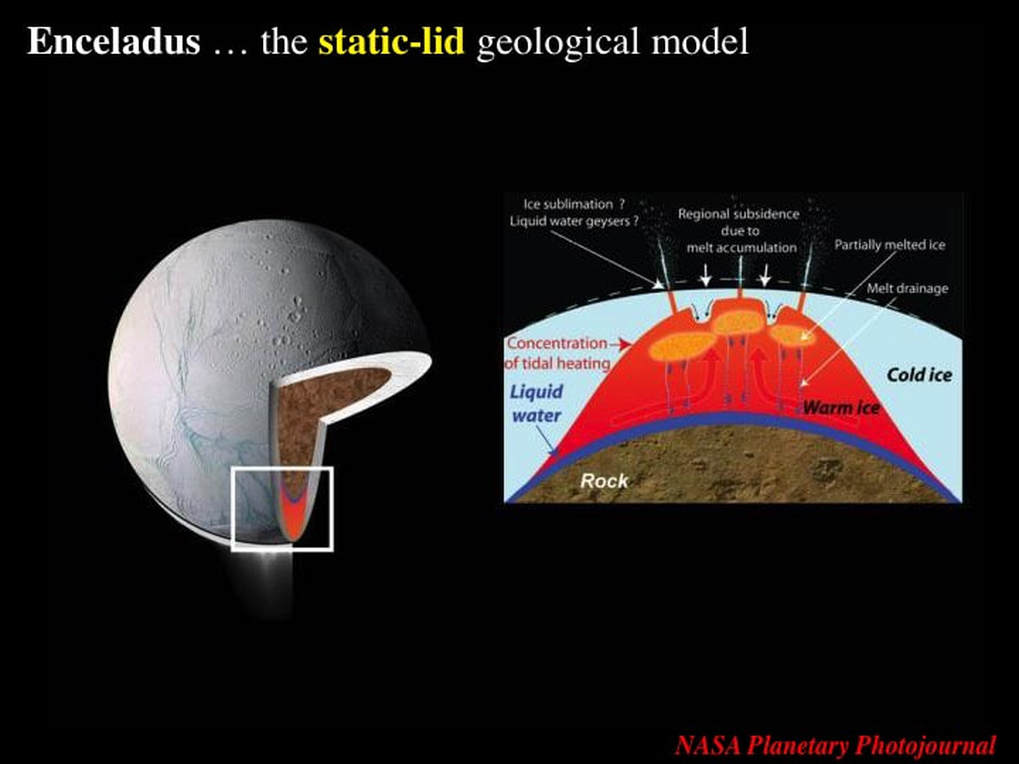

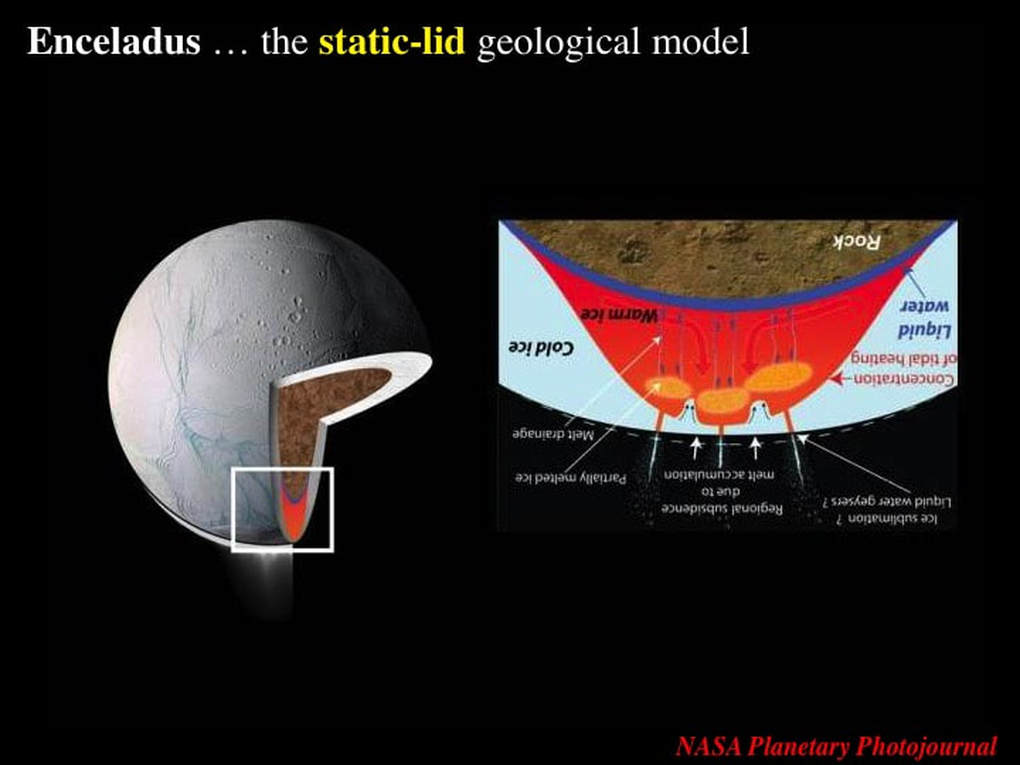

This diagram illustrates how a spreading ridge operates on Earth to generate new crust. This is plate tectonics, which is what gives rise to continental drift. In planetary geological terms, all this moving around of multiple crustal plates is referred to as the mobile-lid model, in contrast to the rigid, immobile crust of Mars or Venus - or the Moon for that matter - which are referred to as the single plate or static-lid model.

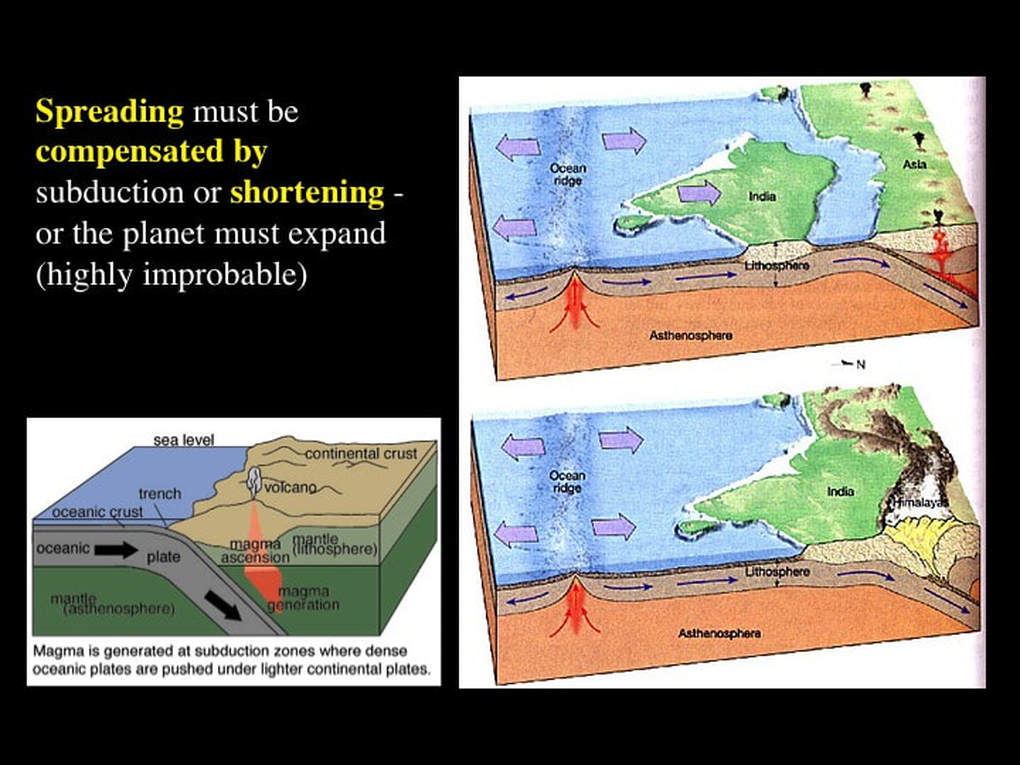

As I've explained here several times before, unless this spreading of the crust is compensated by some form of shortening elsewhere, the planet or moon concerned will expand - significantly : something for which we have no evidence to date anywhere in the Solar System … except for Earth.

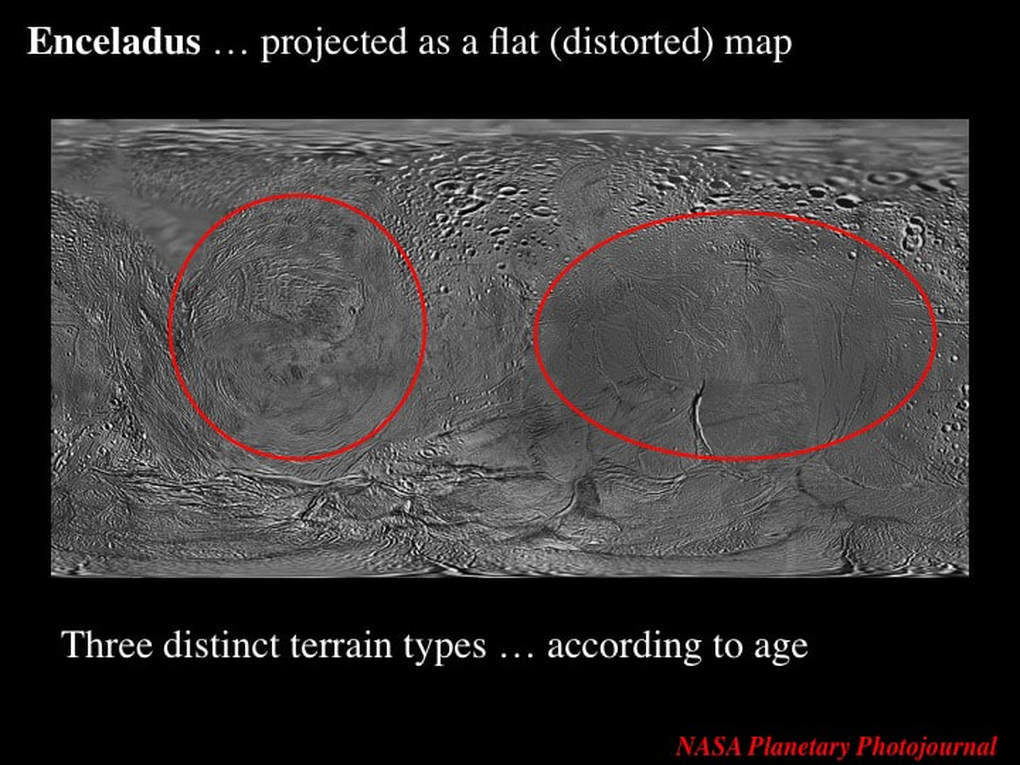

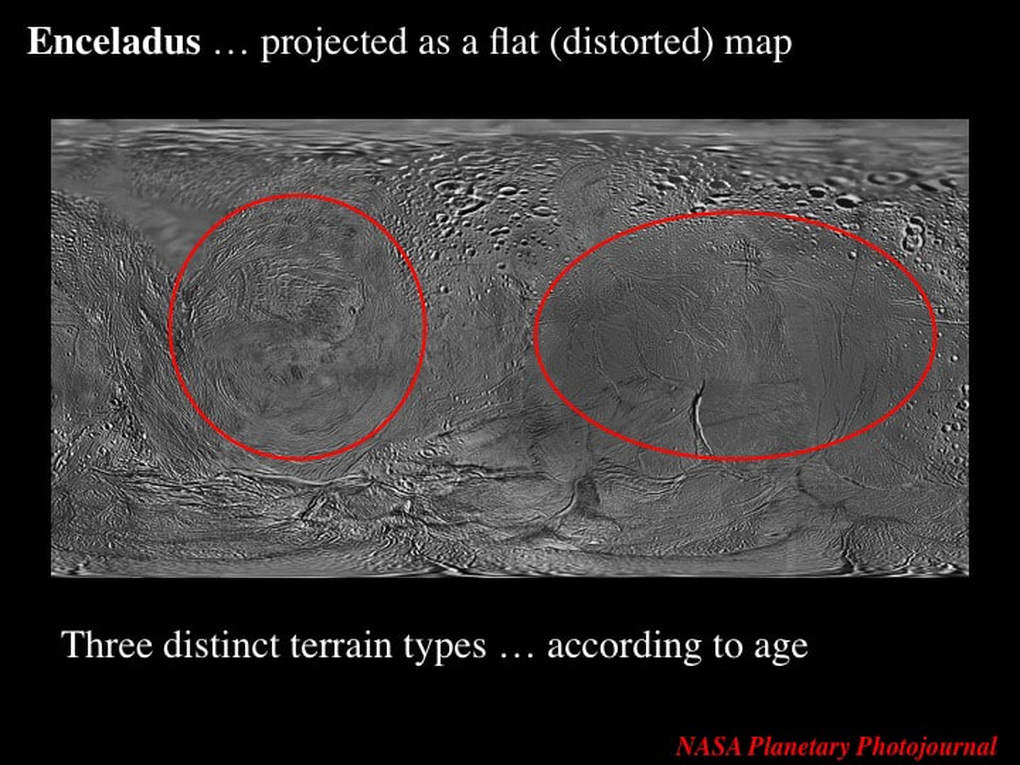

So, what has Cassini found to support the idea that the "Tiger Stripes" really are "spreading ridges" ? NASA recently released this complete map of Enceladus. The distortion of the polar regions is due to the nature of the Mercator projection, which takes a sphere and flattens it out into a rectangular map. This is an amazing image that shows us three types of terrain. To the north - and between the red ellipses - is the oldest terrain, marked by abundant impact craters. Around the South Pole is a terrain with almost no impact craters (difficult to see because of the polar distortion),which tells us that it's the youngest terrain on the moon. Within the two red ellipses is a terrain of intermediate age that has a modest density of impact cratering.

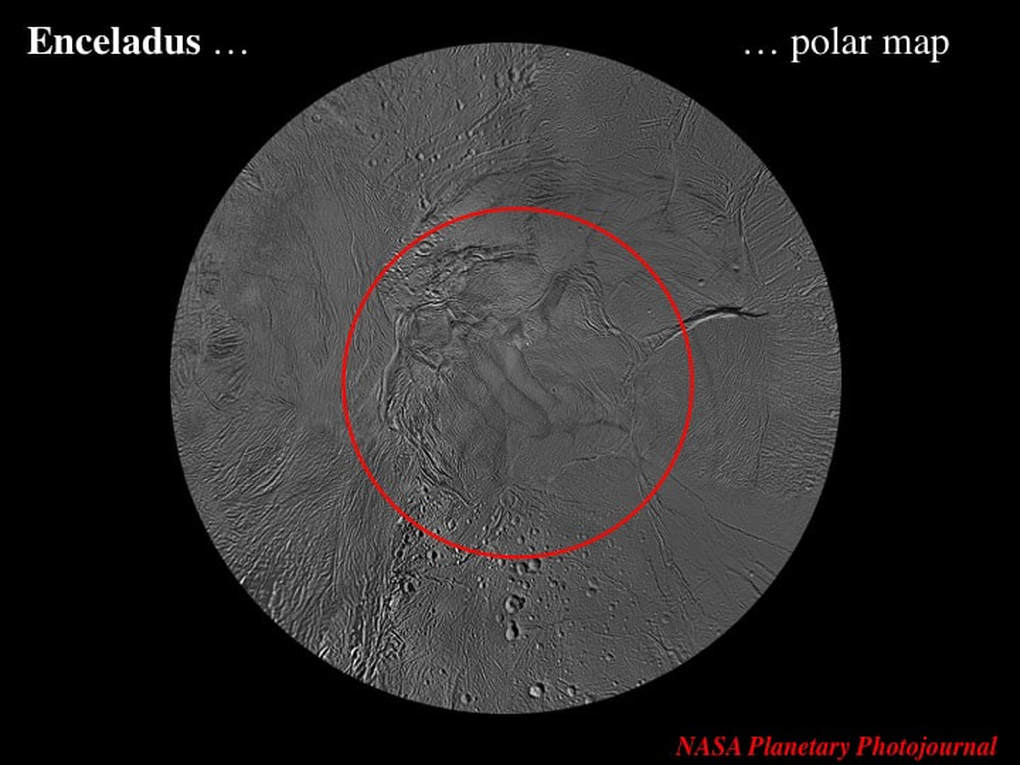

Looking directly at the South Pole of Enceladus we can clearly see the pockmarked old terrain, and the young terrain with the "Tiger Stripes". The intermediate age terrain is less evident in this image, but the "Tiger Stripes" are clearly surrounded by a nearly complete ring of ridges.

If we now look at the South Pole, with lighting conditions that enhance topographic relief, we can see that this ring of ridges is a chain of mountains formed by the shortening of the crust of the ice moon. At last … planetary geologists have demonstrated the existence of something that looks like plate tectonics, somewhere other than on Earth.

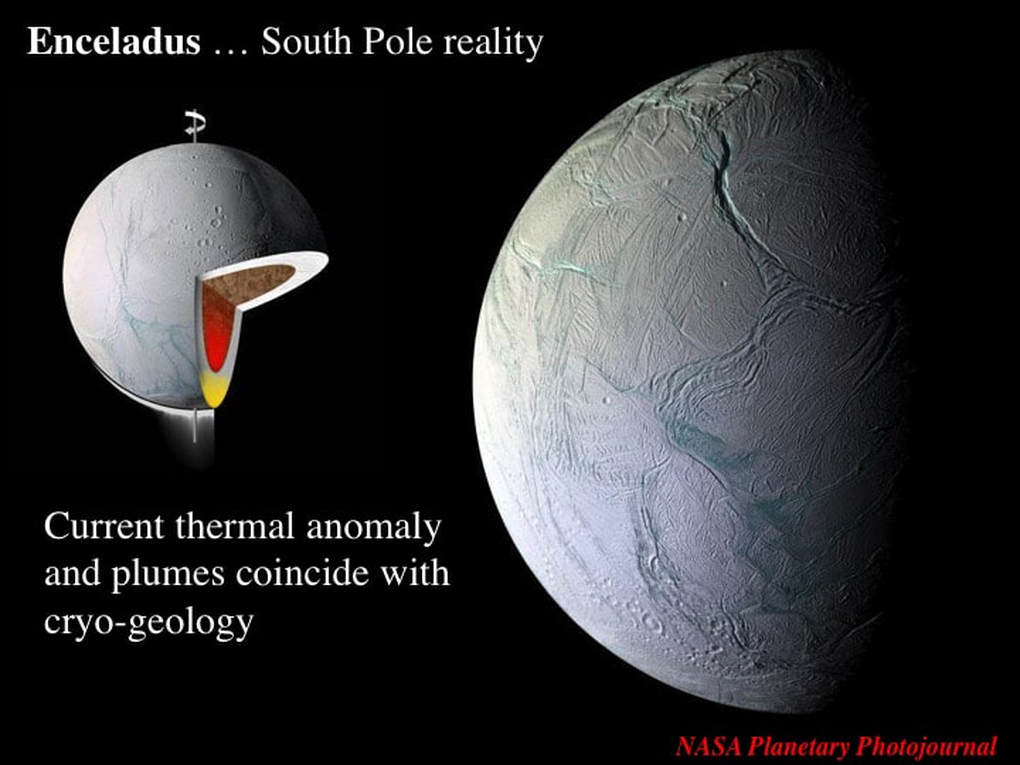

On Enceladus, a massive thermal anomaly or "hot spot" - coincident with spreading or extension associated with the "Tiger Stripes" and surrounded by a ring of mountains representing shortening or contraction - points to predominantly vertical movement. According to the February 2010 publication in Nature Geoscience, the anomaly is probably the result of tidal heating of Enceladus as it is alternately squeezed and relaxed during its elliptical orbit in Saturn's powerful gravity field. Somewhere on the moon the icy crust was thinner - or had some other local weakness - that allowed the warm interior to locally rise vertically toward the surface, much like the oil in a lava lamp - or if you're too young to know what a lava lamp is, like bubbles rising through oatmeal in a saucepan on the stove ! A bubble that rises vertically toward the surface will always expand because the pressure decreases with decreasing depth, which means that it will attempt to stretch the surface it's rising towards. On Enceladus this stretching of the moon's surface is manifested as the "Tiger Stripes" acting like spreading centres that create new young icy crust. The ring of mountains - that you can just make out in this image - represents a crumpling at the edge of the thermally driven stretching that compensates for the extension and prevents the moon from expanding.

Now, let's orient the model to the real world of Enceladus' South Pole so you can better see how it corresponds (bottom image). Why is all this action focused about the moon's South Pole ? Quite simply because if any spinning body has a large patch of anomalous crust, as here, it will wobble, and the mechanics of wobbling are such that the spinning body will reorient itself such that the anomaly that caused the wobble in the first place will end up sitting over one pole or the other of the spin axis. For the technically minded, it's all to do with the principle of least work - or least "wobble" - and the attainment of equilibrium.

Now, let's orient the model to the real world of Enceladus' South Pole so you can better see how it corresponds (bottom image). Why is all this action focused about the moon's South Pole ? Quite simply because if any spinning body has a large patch of anomalous crust, as here, it will wobble, and the mechanics of wobbling are such that the spinning body will reorient itself such that the anomaly that caused the wobble in the first place will end up sitting over one pole or the other of the spin axis. For the technically minded, it's all to do with the principle of least work - or least "wobble" - and the attainment of equilibrium.

So, now that you understand the latest thinking regarding Enceladus' South Pole, you can understand the significance of the terrain within the two red ellipses in this map of the ice moon. Planetary geologists think that these are two areas of older ice representing two periods when the same phenomenon we see today at the current South Pole occurred in different parts of the moon's icy crust at different times during the history of the Outer Solar System. In short, cryovolcanism is a repeating episodic phenomenon on Enceladus, and not a recent fluke. Let’s now leave Enceladus and look at another of Saturn's celebrated moons : the enigmatic Iapetus.

Iapetus has been enigmatic ever since Giovanni Cassini in the 17th century realised that it brightened and darkened as it orbits Saturn. Over 300 years ago Cassini worked out that this must mean that one side of the Moon is bright and the other side is dark. and that the moon always presents the same face to its host planet Saturn.

300 years later we now know that Saturn has a giant dust ring - only visible in infra-red light - dust that falls onto the leading hemisphere of the otherwise bright ice moon Iapetus that orbits just inboard of this ring.

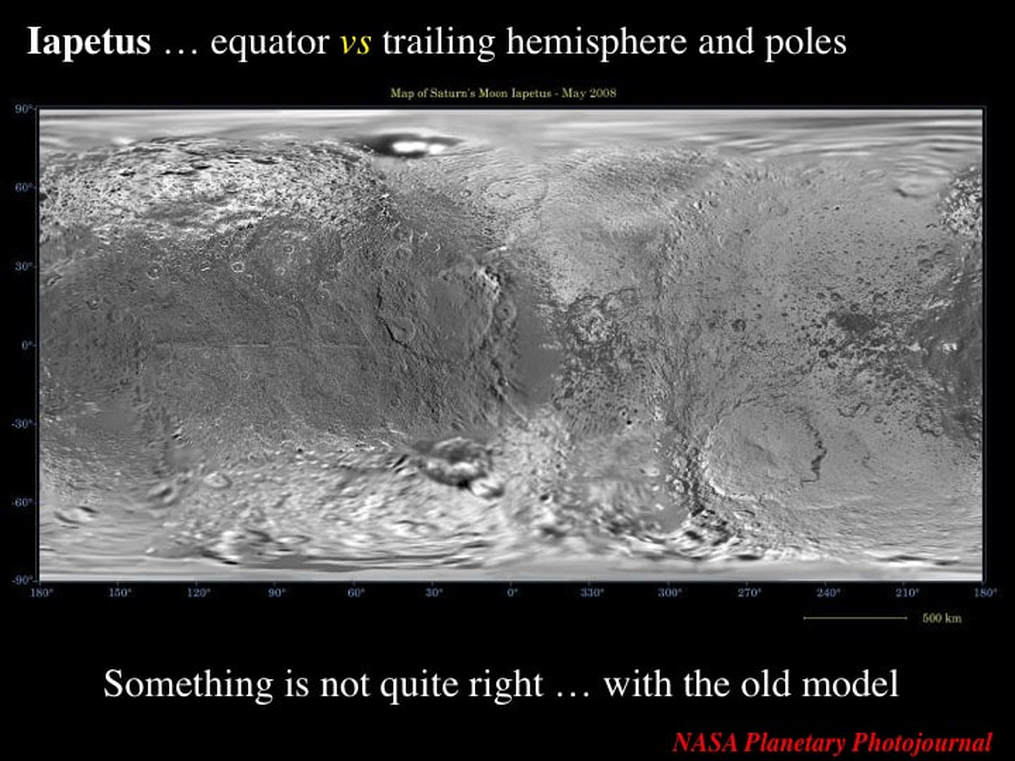

However, as pointed out by planetary scientists in a January issue of the journal Science, there's something very wrong with this explanation. From a purely mechanical perspective, dust falling onto a moon that is tidally locked to Saturn should cover the entire leading hemisphere of the moon, and only the leading hemisphere. Now, look carefully at these images of Iapetus : the poles are dust-free on the leading hemisphere, and the dark dust encroaches onto the trailing hemisphere.

This map of the entire moon emphasises how the poles are clean, and the dark dust is focused along the equator, well into the trailing hemisphere. What gives ? What's the missing variable ? Temperature ! The Science paper resurrects a theory first proposed in 1974 that proposed that dark terrain is slightly warmer than clean ice, because it absorbs the heat from sunlight, rather than reflecting it back into space. This leads to higher rates of sublimation of ice, especially at the equator where the Sun is overhead. As the ice sublimates, any impurities in the ice will get left behind and added to the dust that fell on the moon's surface. Because Iapetus has no atmosphere, the molecules of sublimated water ice jump across the surface of the moon on ballistic trajectories like a cannon ball fired from a cannon. Depending on local temperatures in different parts of the moon, a given water molecule will jump between 500-750 km before coming back to the moon's surface. That half to one third of the moon's diameter ! When these water molecules land near the poles, which are cooler than the equator - just like on Earth - they re-precipitate there as ice, covering any externally derived dust that had fallen on the leading hemisphere. Because there's less dust on the trailing hemisphere, the average temperature there is cooler than the leading hemisphere, but the equator is still the warmest latitude. Hence sublimation of ice still occurs along much of the equator, giving rise to a discontinuous belt of impurities that are left behind. In short, the distribution of dust on Iapetus is a function of a very dynamic process of dust deposition, sublimation, the build-up of impurities left behind, and the re-precipitation of ice that can blanket and brighten both externally derived dust and internal impurities.

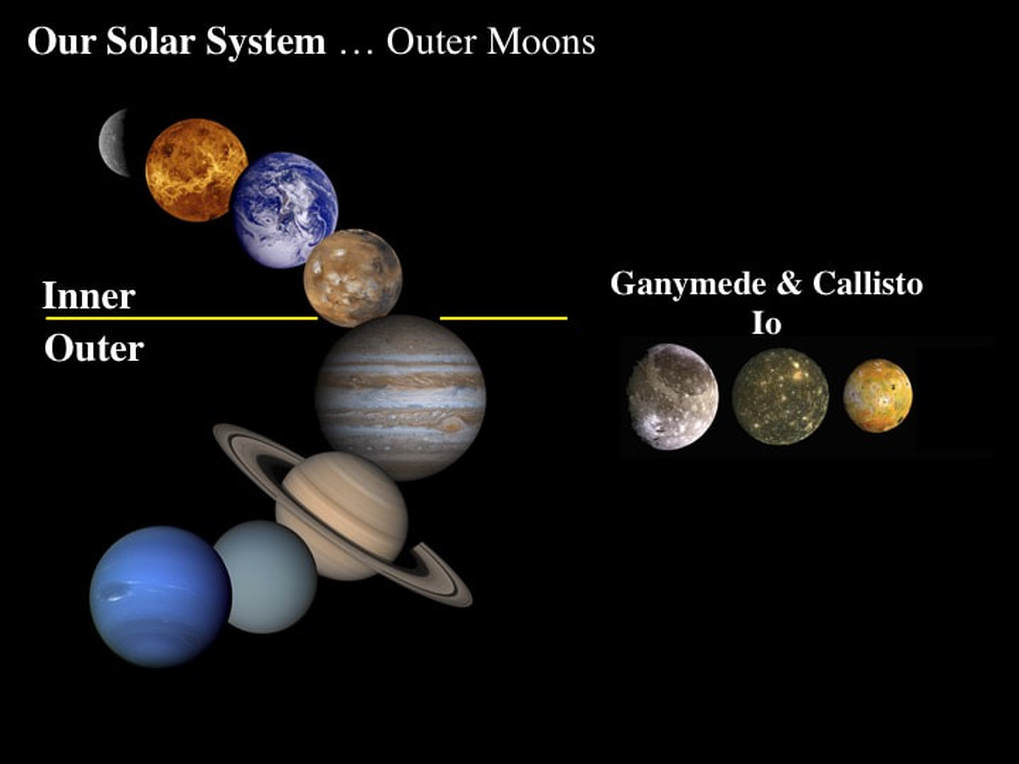

Changing planets, another paper in a January issue of the journal Science asked a pretty basic question about two of Jupiter's moons.

Ganymede and Callisto are pretty much twins as ice moons go : same size and same composition. So why are they so different ? Ganymede has differentiated into a rocky core and an icy mantle and crust, and its surface shows all the signs of having once been very active. Callisto on the other hand is a homogeneous mix of rock and ice right through to its core, and its surface appears to have been dead from the very beginning. The fundamental difference could be explained if Ganymede had been warmer than Callisto during its early history : but why ? Remember, according to the first law of thermodynamics, energy can be changed from one form to another - but it cannot be created or destroyed. So, the kinetic and potential energy of an impactor hitting an ice moon can both be transformed into heat. According to planetary scientists, Jupiter's gravity would attract potential impactors, and Ganymede's position closer to Jupiter than Callisto would lead to 350% more energy being pounded into Ganymede : energy that would allow the temperature of the moon to rise enough for the rocky components of the moon to begin to sink through the ice component. This would have led to runaway heating of the moon as the potential energy of the sinking rocky components was itself transformed to even more heat. Poor old Callisto was - literally - left out in the cold and never started to heat up, or to differentiate. Hence the difference between the two moons !

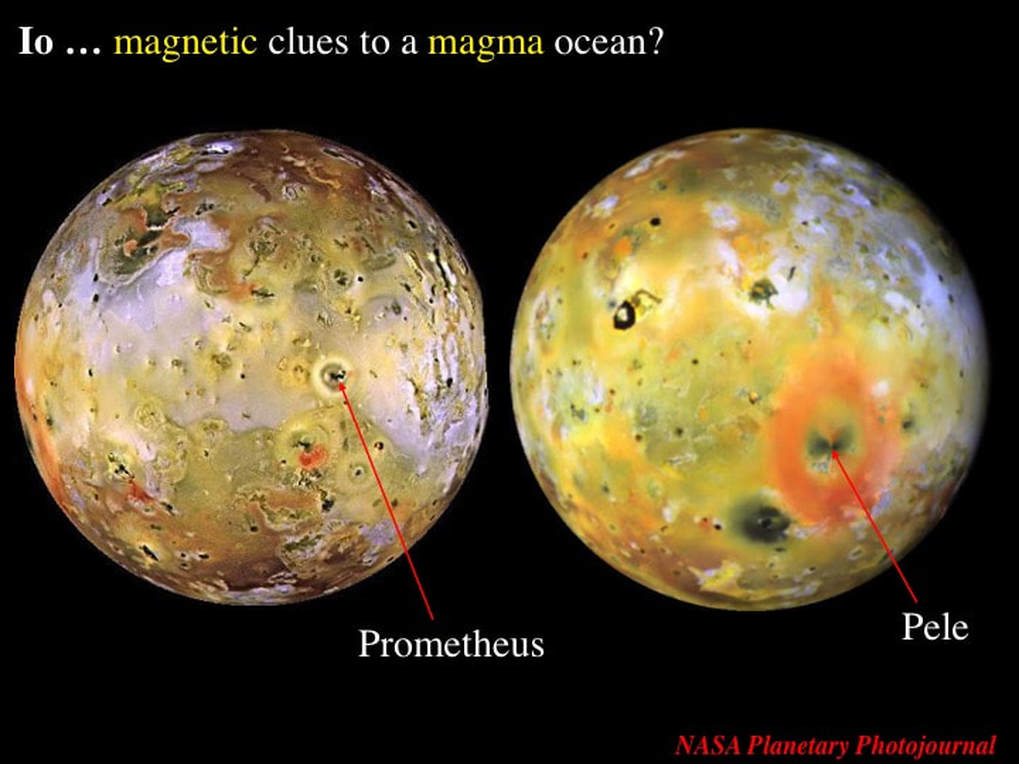

Finally, at the December 2009 meeting of the American Geophysical Union, planetary scientists reported on mathematical models they had constructed to explain the interaction between Jupiter's planetary magnetic field and Io, its volcanically active and rocky moon. I don't claim to understand all the details of the physics, but their hypothesis is that the magnetic data require a global ocean of molten rock about 50 km beneath the moon's surface … and that's all I can tell you about that for now !

Proudly powered by Weebly