|

MARS I

|

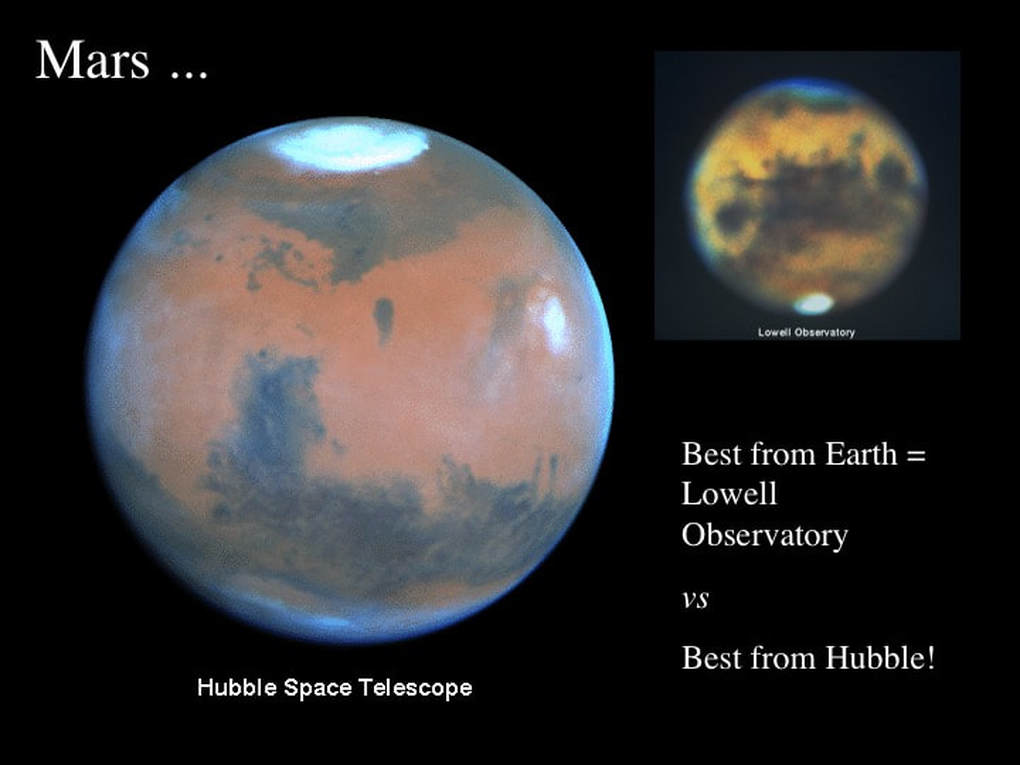

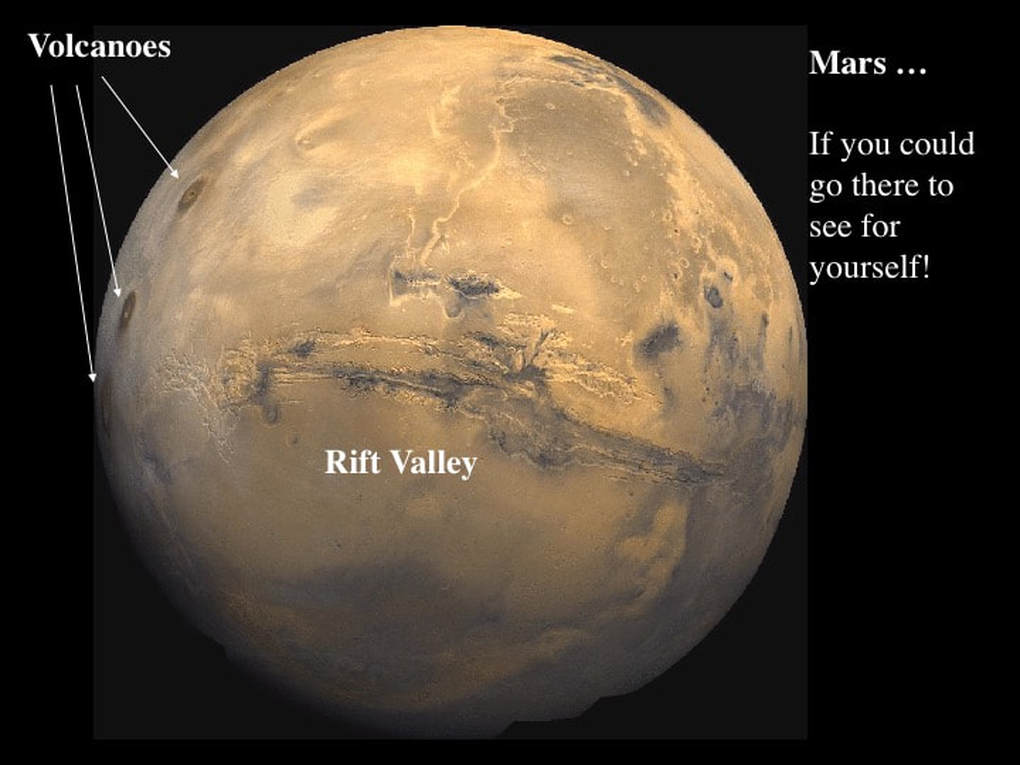

Despite its small size, about half the size of Earth, Mars has some incredibly large geological features. These include the highest mountain, the largest rift valley and the largest impact basin. As amateur astronomers, when we look at Mars through our telescopes, we hope that steady seeing will allow us to make out some of its surface markings. These usually look like dark blotches on a red to orange disk, best seen in the Martian southern hemisphere, or the white polar ice caps. Although pictures taken by Hubble are sharper than the best Earth-bound picture taken by the Lowell Observatory, they can only show dark patches and ice caps

On the other hand, various satellites, from Viking and Mariner to the more recent Orbiter series, have taken detailed photos of a range of amazing topographical features such as volcanoes and valleys. So what’s the link between what we see through our telescopes and the planetary geology of Mars? Well, except for the ice caps, none! This is pretty depressing, let me explain. Topographic maps of Mars map highlight two principal terrains: the heavily Cratered Terrain in the South, and the smooth Northern Plains. These are the first order divisions, but let’s move to the next level of detail.

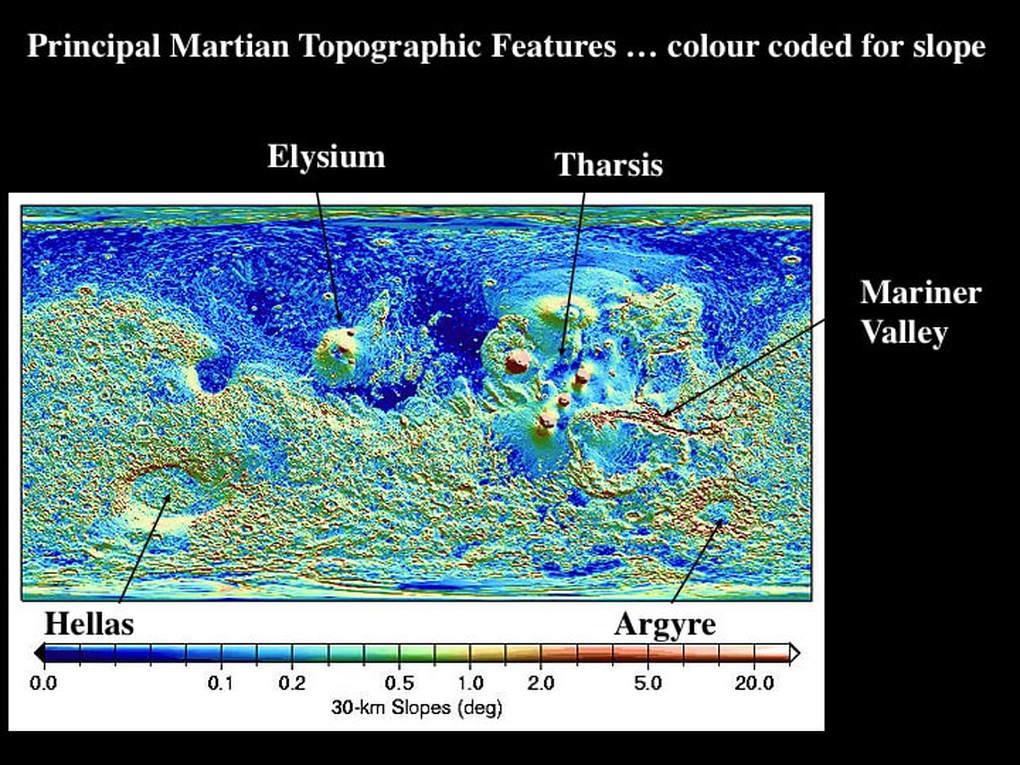

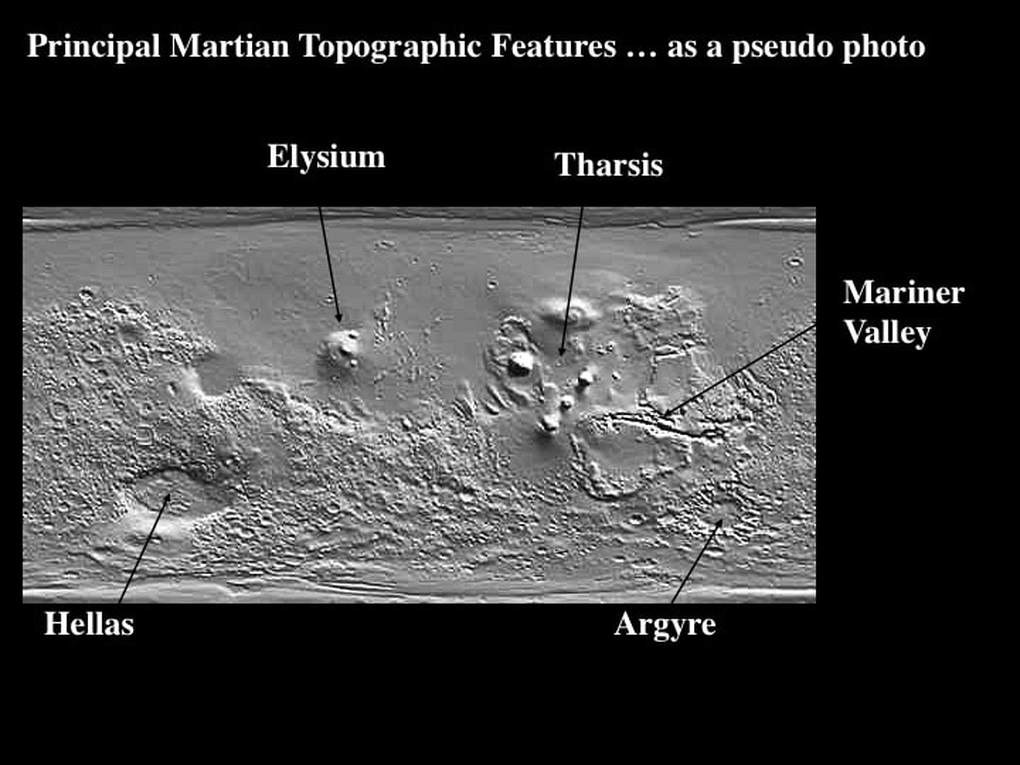

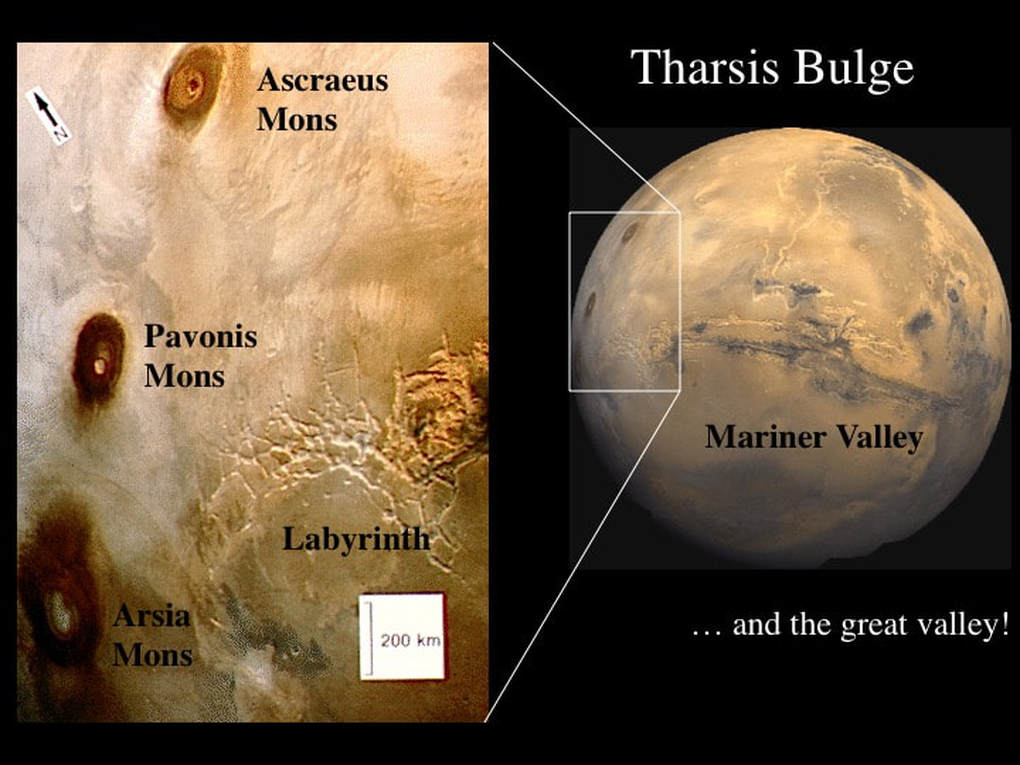

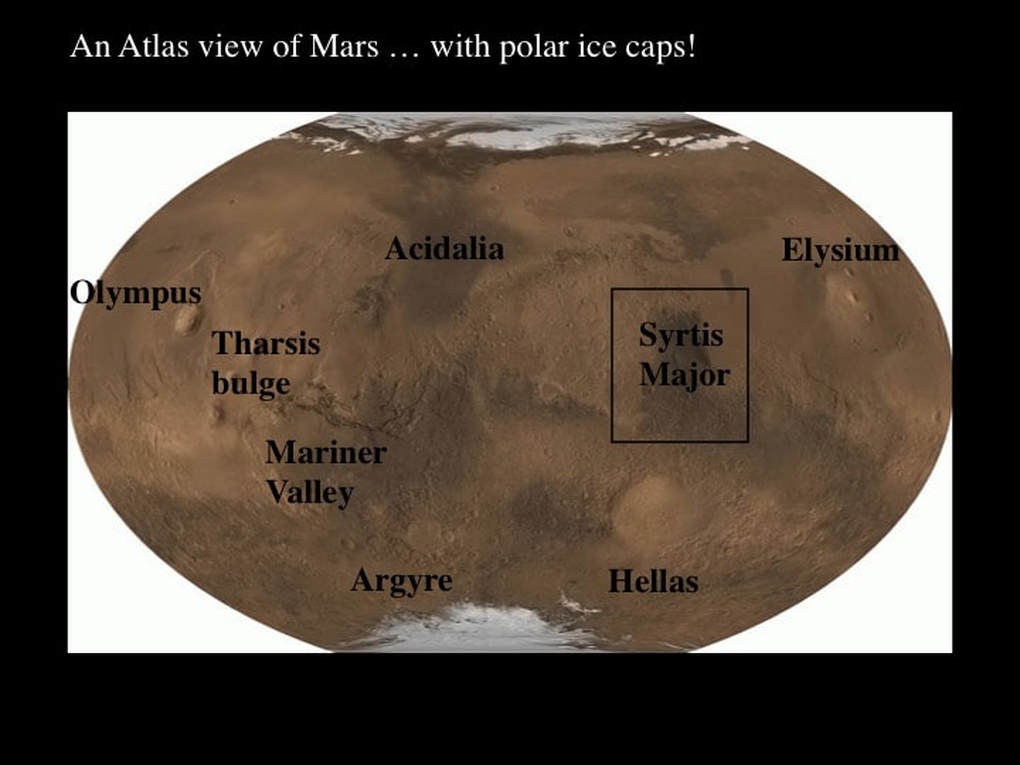

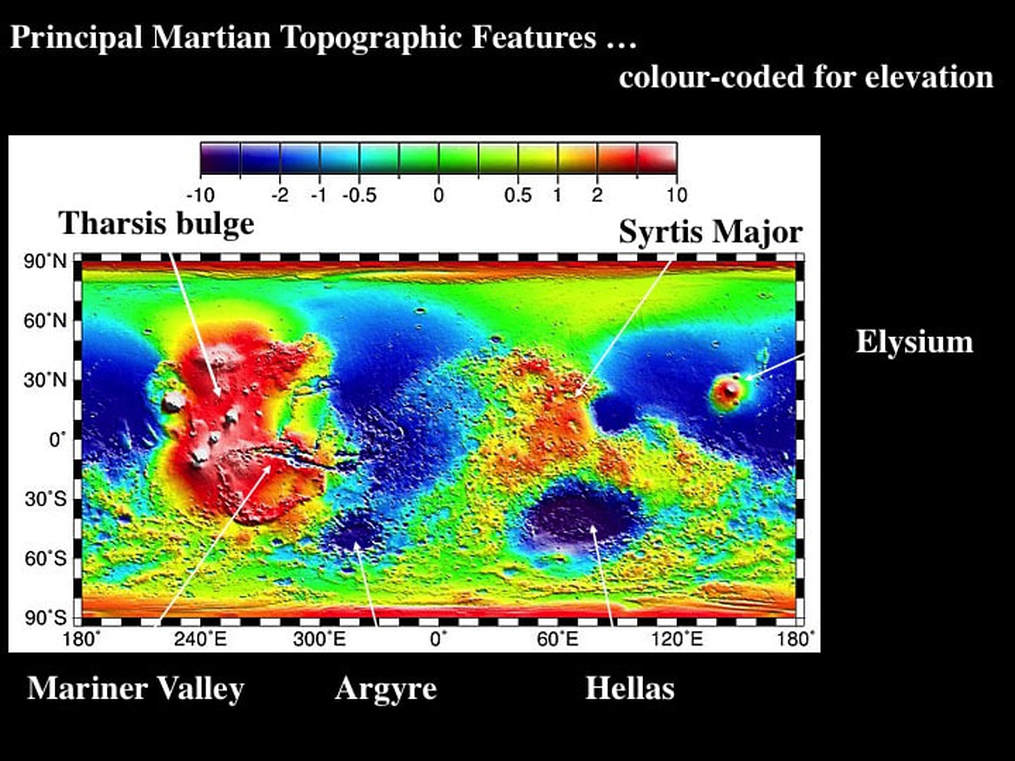

Tharsis is a huge plateau or bulge that rises gently from both the Cratered Terrain and the Northern Plains and is peppered with several giant volcanoes. To the West of the Tharsis bulge is the smaller Elysium bulge which also has volcanoes on it. East of the Tharsis bulge is a huge valley system called the Valles Marineris in honour of the Mariner probe; we can call it the Mariner Valley. The upper reaches of the valley system start in the SE corner of the Tharsis bulge, and end at the boundary between the Cratered Terrain and the Northern Plain. In the southern part of the Cratered Terrain are two huge elliptical areas with flat interiors called Hellas and Argyre.

The volcanoes and valleys are easy enough to understand, but what are the Northern Plains, and what are Hellas and Argyre plains doing in the middle of the Cratered Terrain ? For that matter, what is the Cratered Terrain anyway ? Heavy cratering means “old”, because if those are impact craters then we know that the main period of impact cratering in the Solar System ended before about 3 billion years ago. So, if the Northern Plains show less evidence for impact cratering, then they must be younger than the Cratered Terrain, just as the smooth lunar Mare are younger than the cratered lunar highlands. Therefore, if we extend this line of reasoning, then the Hellas and Argyre Plains are probably Impact Basins filled with lava.

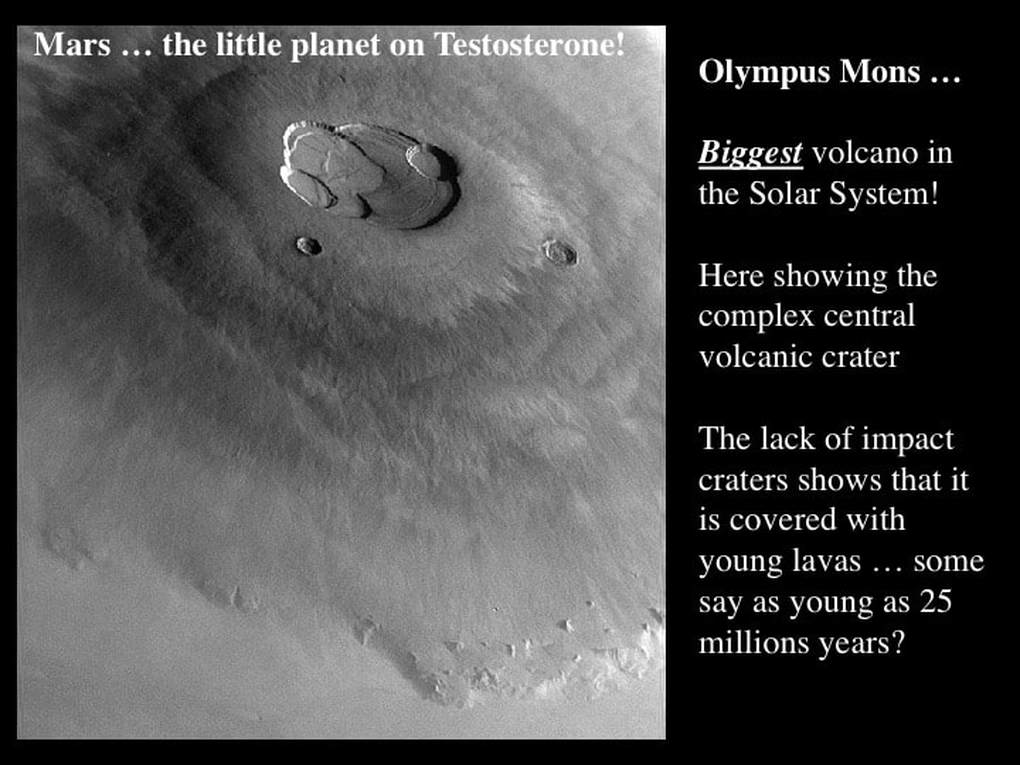

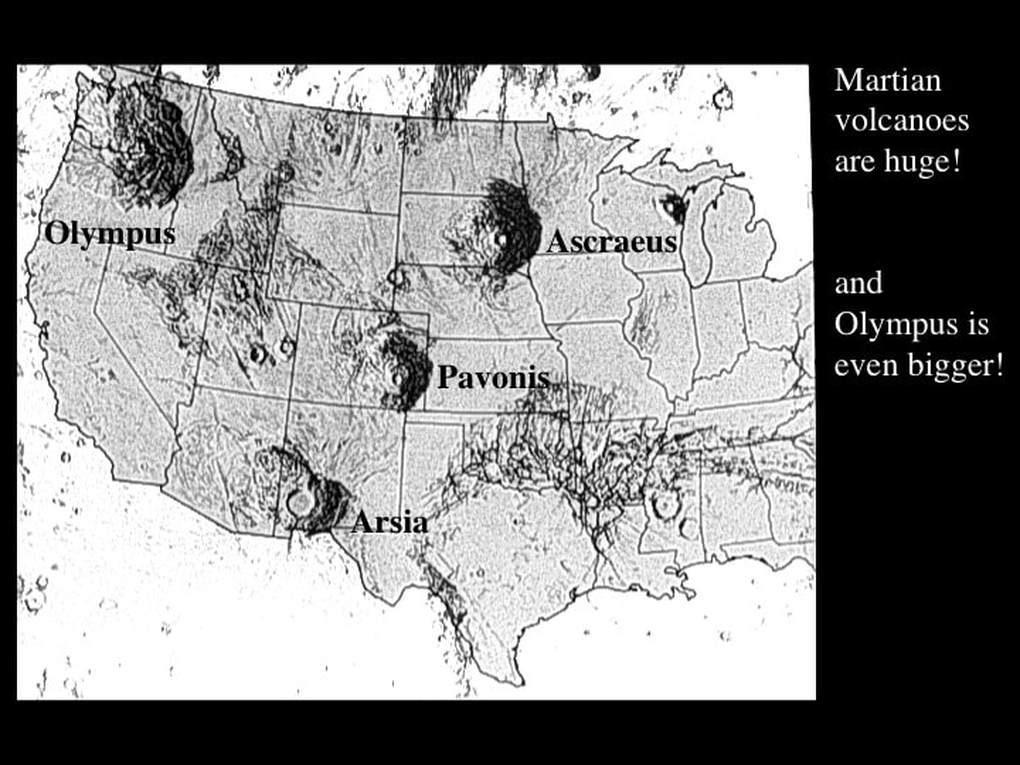

The Tharsis bulge is topped by a line of 3 giant volcanoes on the Tharsis bulge. Each one has a diameter equivalent to the distance from Ottawa to Montréal ! Most importantly, these three volcanoes and much of the Tharsis bulge have no impact craters. This means that the bulge and its volcanoes have been re-surfaced by lava flows after the time of major meteorite bombardment in the Solar System. Some planetary geologists have proposed that the volcanic activity on the Tharsis bulge is extremely young, maybe as young as 25 million years. On the SE edge of the Tharsis Bulge, the upper part of the Mariner Valley shows no impact craters, so it must be younger than 3 billion years old too.

How big are the main elements of Martian topography ? The biggest volcano on Mars is Olympus, perched on the NW side of the Tharsis bulge.

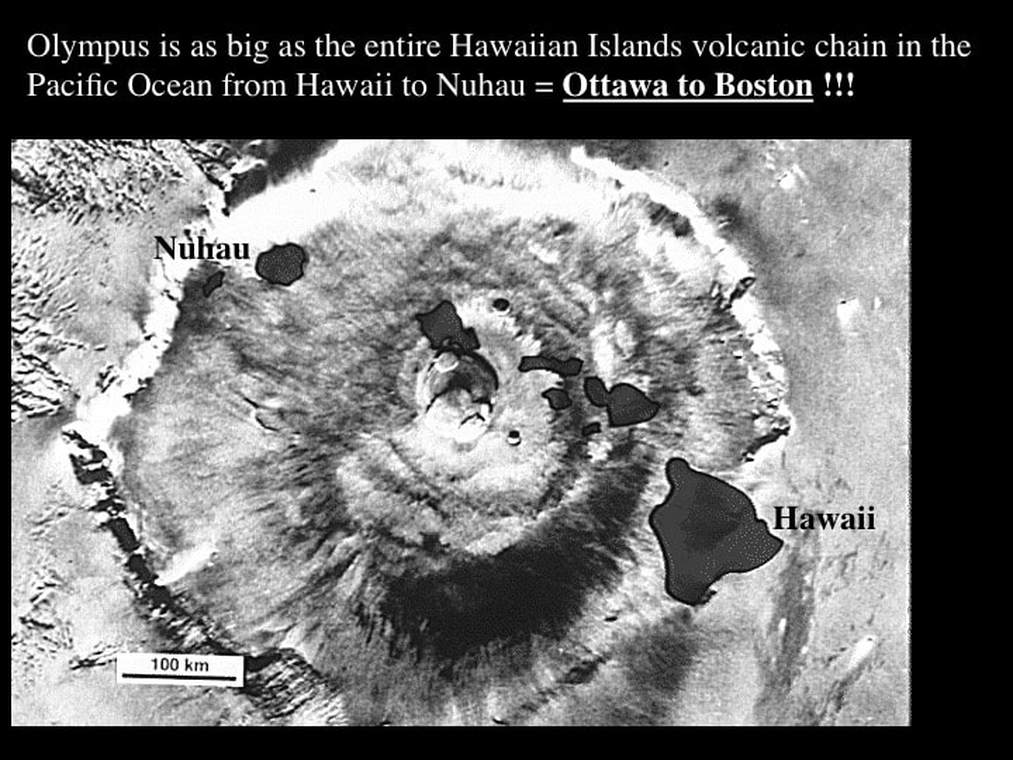

In terms of its diameter, it’s a big as Hawaii and all of its volcanic neighbours ! In other words, it would span from Ottawa to Boston! But Olympus is not just broad in the beam, it’s also incredibly; nearly 3 times higher than Everest, whose peak elevation is a bit less than 10 km, making Olympus about 27 km high. That makes Olympus the largest volcano and the highest mountain in the Solar System !

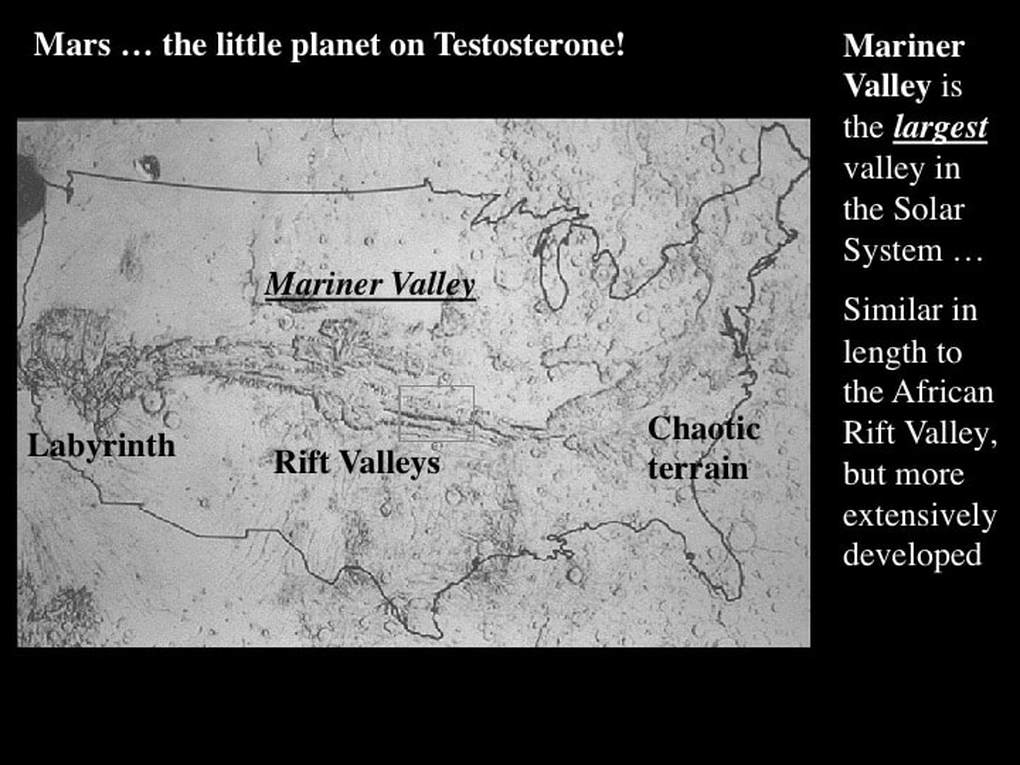

The Mariner Valley would span the entire width of the US; that’s about equivalent to the Great Rift Valley of eastern Africa, but the intensity of its development as expressed by its branches, and its depth, have no equal in the Solar System.

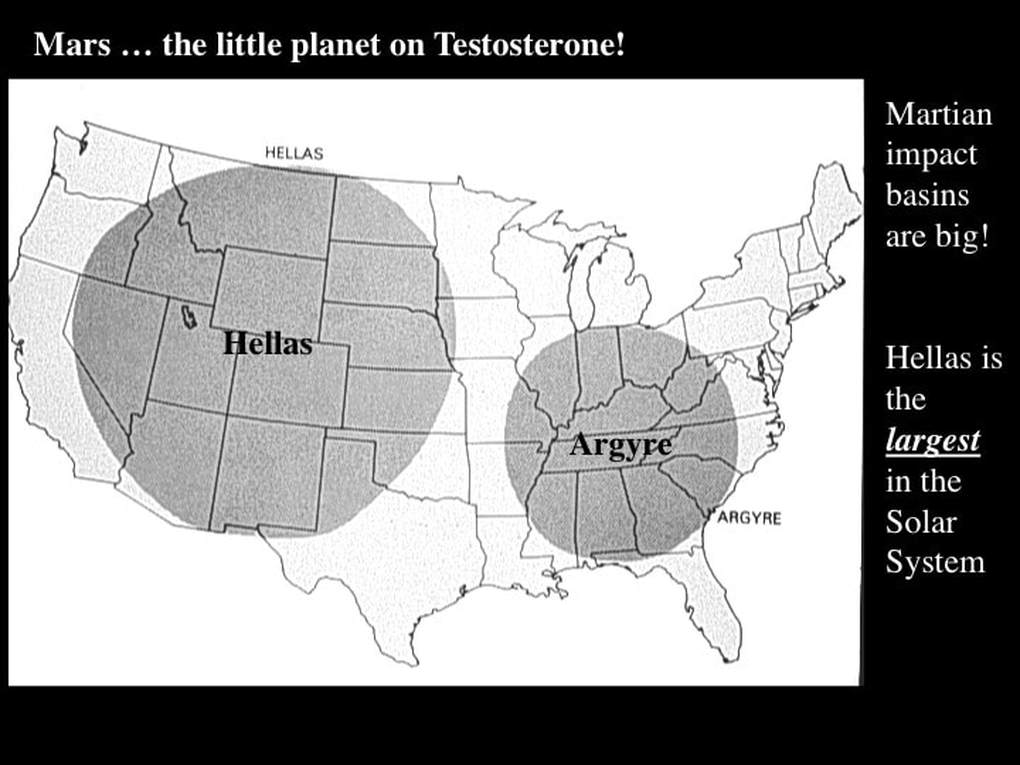

Hellas is the largest Impact Basin or Mare in the Solar System. It is so large, more than 2000 km, it would fill the western and central US ! Compare that with about 1200 km for the larger lunar Impact Basins.

The point I’m trying to make is simple. Mars might be a bit on the small size as planets go, but it’s got some pretty impressive topography. So, if Mars is so well endowed physically, how come we don’t see any of this through telescopes - not even Hubble ? If we’re not seeing this impressive topography through our telescopes, what exactly are we seeing ? The dark patch that is most readily observed through amateur telescopes is Syrtis Major, simply because it’s the biggest and darkest patch. However, it is not located near any of the major topographic features that Mars is famous for; Syrtis Major is simply a slightly elevated area in the Cratered Terrain, near the margin of the Northern Plains. So, why is it so obvious through our telescopes, while the really important features fade into obscurity ?

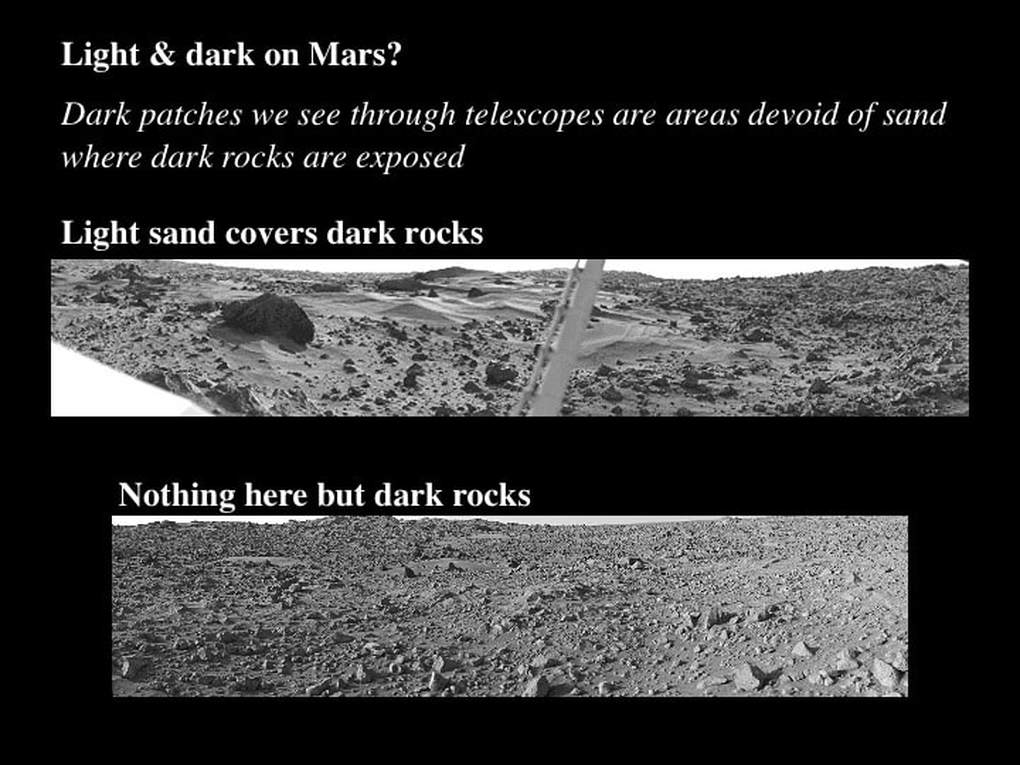

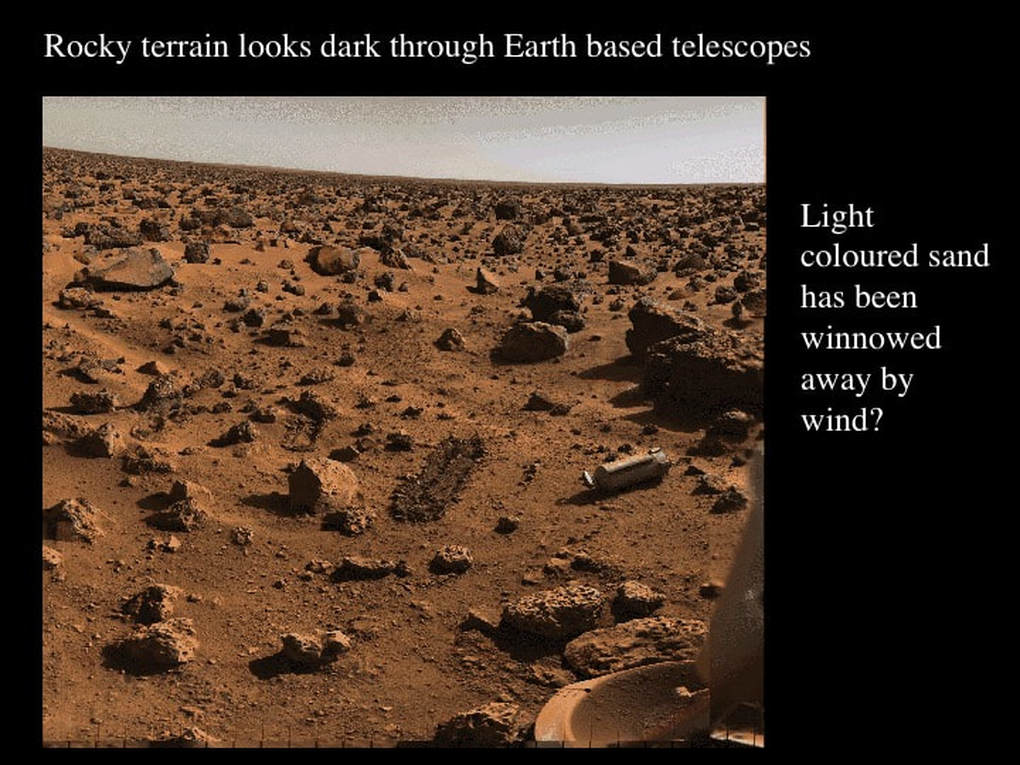

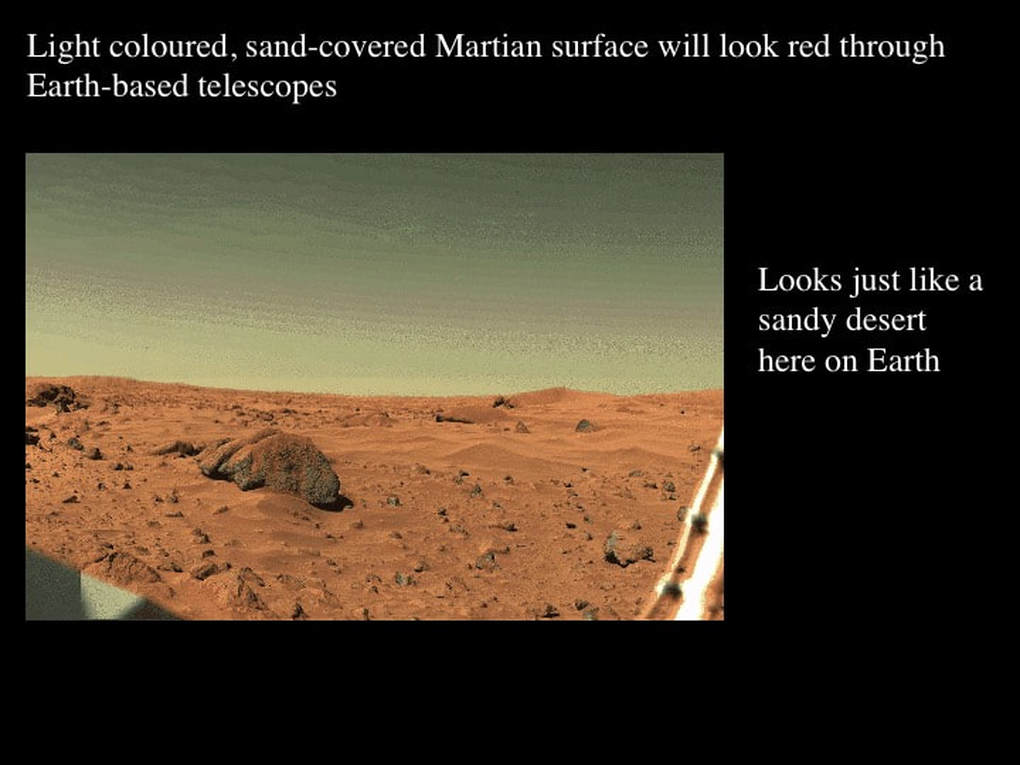

It turns out that the colours of the Martian surface are simply related to the distribution of light coloured sand vs dark coloured volcanic rocks. In other words, what we see through our telescopes is simply a reflection of the distribution of sand on the Martian surface. Syrtis Major is an area where sand has been removed, presumably by wind : see also the images below.

Proudly powered by Weebly